This is a rudimentary translation of articles from my book “Goddess Culture in Israel“. While it is far from ideal, it serves a purpose given the significance of the topic and the distinctiveness of the information contained. I have chosen to publish it in its current state, with the hope that a more refined translation will be available in the future.

Dorothy Garrod

Dorothy Garrod (1892-1968) dedicated her life to the study of Prehistory, driven by the belief that it sheds light on the essence of humanity and guided by a spiritual sense of Religious purpose. Her work aimed to foster love and unity, envisioning a better future for humanity. Despite being unmarried and childless, her legacy lives on through her extensive research and publications. Regarded as one of the foremost prehistoric archaeologists in the Land of Israel, her doctoral thesis on the Stone Age in Carmel remains a fundamental reference in the field of prehistoric studies.

Garrod hailed from an affluent English academic family and was a strikingly beautiful and spiritually inclined young woman. At the age of 21, she converted to Catholicism, reflecting her deepening spiritual journey. Despite plans for marriage and an engaged future, tragedy befell her family during the First World War when all three of her brothers, along with her fiancé, lost their lives. This pivotal moment altered the trajectory of her life in unforeseen ways.

Perhaps as a response to the tragedy and seeking solace for her family, Garrod embarked on an academic path. Studying history, she journeyed to Malta in 1920, where her family was residing at the time. Encouraged by her father, she engaged in excavations led by local archaeologists, notably Themistocles Zammit, who unearthed prehistoric temples associated with ancient Goddess cultures, such as the hypogeum and other Megalithic complexes. Notably, in 1921, the renowned feminist archaeologist Margaret Murray was also active in Malta, suggesting a potential connection or awareness between the two scholars.

Indeed, Garrod’s encounter with the ancient temples and prehistoric sites of Malta sparked her fascination with prehistory. This led her to delve into the religious practices of ancient peoples, prompting a research trip to explore caves adorned with rock paintings in southern France. It was during this journey that she crossed paths with Henri Breuil, subsequently becoming his student and relocating to Paris for further studies under his guidance from 1922 to 1924. In Paris, she also encountered Pierre de Chardin and was influenced by his ideas, aligning herself with the circle of spiritual prehistorians. Engaging in excavations across France and managing various prehistoric sites, she later pursued research on English prehistory for her master’s thesis and conducted excavations in Gibraltar, where she made significant discoveries of Neanderthal remains. In essence, Garrod emerged as a prominent figure in prehistoric research and excavation management in Europe.

Garrod’s arrival in Israel in 1928 coincided with a period of robust archaeological activity under British Mandate rule. Embarking on her first excavation at Shuqba Cave in Nahal Natuf, a tributary of Nahal Ayalon, she unearthed traces of an ancient and previously unknown culture. Subsequently, Garrod turned her attention to the caves of Mount Carmel, including El Wad, Tabun, Skhul, and Kebara, where she made further discoveries linked to this enigmatic culture. Recognizing the significance of these findings, she astutely identified and named this culture the “Natufian culture,” marking a pivotal moment in the understanding of prehistoric societies in the region.

Garrod’s excavations were not only groundbreaking in terms of archaeological discoveries but also in promoting feminist and egalitarian values [1]. She actively engaged Arab women as workers in her projects, emphasizing their capabilities and arguing that they excelled in tasks requiring patience, attention to detail, and a holistic perspective. Garrod believed that women were better suited for most roles except those demanding significant physical strength. Consequently, she structured her camps to predominantly employ women, with men handling labor-intensive tasks like stone and dirt removal. This approach reflected her commitment to gender equality and challenged traditional gender roles in the field of archaeology.

Garrod’s extensive excavations, conducted over approximately eight years, revealed a significant insight: between the 13th and 10th millennia BC, an advanced Human culture flourished in Israel and neighboring regions. This culture represented a pivotal transition from small bands of hunter-gatherers, who were nomadic and inhabited caves, to larger settled communities poised to embrace agriculture and permanent dwellings. Her findings shed light on a crucial phase in Human history, highlighting the emergence of more complex societal structures and the initial stages of sedentary lifestyles.

The primary focus of Garrod’s work and the site for which she is renowned are the prehistoric caves of Mount Carmel. Over five years, she conducted excavations at various locations on Carmel, culminating in the publication of her doctoral thesis, “The Stone Age on Mount Carmel.” [2] This seminal work, considered a masterpiece, continues to inform research in the field. In 1935, she uncovered the prehistoric site at the Benot Yaakov Bridge, dating back 780,000 years. Subsequently, Garrod embarked on excavations in Bulgaria, France, and other global locales. In her later years, she returned to the Middle East, engaging in excavations and research in southern Lebanon.

The mystery of Natufian Culture

Between 20,000 and 13,000 BC, the Aurignacian culture gave way to the Kebara culture, named after the Kebara cave in southern Carmel. It’s important to recognize that in prehistoric cultural transitions, the shifts are not akin to the stark contrasts seen between, say, European and Chinese cultures. Instead, there’s often continuity in the hunter-gatherer way of life, with changes primarily observed in tool technology, such as the transition to blades in the case of the Kebara culture.

But in the years that followed, Between 13,000 and 9,500 BCE, a significant shift occurs with the emergence of the Natufian culture. This marks a notable leap in Human evolution, particularly in the region encompassing the Land of Israel and its surroundings. The Natufian culture stands out as a transitional phase between hunter-gatherer societies and the establishment of agricultural-based communities. Notably, it was the first culture globally to construct permanent dwellings and settlements, domesticate animals, produce lime, and engage in various other innovations.

Humans who were part of the Natufian culture, found only in the Land of Israel and the surrounding area, likely began cultivating plants on a small scale, which eventually evolved into crops like wheat, barley, flax, and legumes. Alongside this agricultural activity, they supplemented their diet by gathering and hunting. What set the Natufians apart was their transition to a sedentary lifestyle, living permanently in the same place. They constructed the earliest permanent structures, either within caves or in small, independent settlements. Caves used by the Natufians were typically large, well-lit spaces, often featuring rock ledges and terraces. Some structures were built inside the caves, while others were situated nearby. Prior to the Natufian culture, cave dwellings were used for temporary shelter rather than permanent habitation.

The Natufian culture boasted an advanced material culture, featuring grinding craters and sophisticated stone and bone tools. They engaged in long-distance trade, indicating a sense of cooperation and community among them. Their artistic endeavors flourished, particularly in body adornments and figurines, some of which were of an erotic nature, highlighting the reverence for the Human form. They practiced burial customs distinct from their predecessors, often removing skulls—considered sacred—from bodies and interring them separately, along with jewelry and other objects. The skeletons were typically arranged in a fetal position, adorned with strings of beads around the head, neck, or hands. These practices reflect a complex and developed belief system, with a significant emphasis on the concept of life after death.

The Natufian culture is associated with the emergence of the first figurines depicting Human-like figures, albeit with distinctive features. Some of these figurines bear a resemblance to astronauts, a notion popularized by proponents of alternative theories like those proposed by Erich von Daniken. For example, in the El Wad Cave excavation in Carmel, a figurine depicting a being with a large head and eyes reminiscent of an alien was uncovered. Similarly, at the Einan settlement, an astronaut-like head figurine was discovered, among others found in various locations. Proponents of these alternative theories suggest that these figurines may hint at the possibility of extraterrestrial intervention in ancient Human civilization. They propose that beings from outer space may have arrived on Earth during this period and imparted knowledge, such as agricultural techniques, to the indigenous populations.

The Natufian culture endured for approximately 3,500 years, yet much remains veiled about its intricacies. A divergence of this culture, known as the Harifian culture, thrived in the Negev, specifically on Mount Harif. Here, circular dwellings crafted from field stones have been unearthed, each featuring spaces for fires and various amenities. Early forms of art surfaced, alongside the utilization of bone and basalt stone tools, possibly sourced from the Golan. Scholars speculate that these ancient peoples may have dabbled in small-scale agriculture, potentially employing sickles. It’s crucial to recall that this epoch unfolded during the Ice Age when the deserts of today were adorned with verdant greenery..

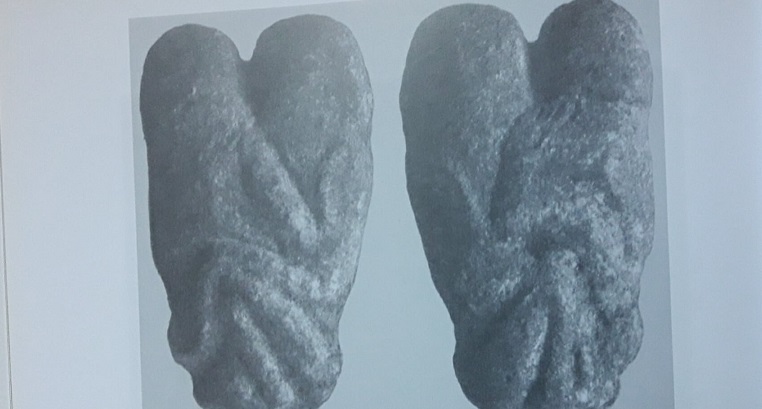

At the Natufian culture sites that Garrod excavated in Carmel, she uncovered engravings etched into stones, showcasing abstract and intricate cognitive abilities, hinting at the potential presence of trance shamanic traditions. Among her discoveries were bone-carved animal figures, an array of jewelry predominantly crafted from oysters and beads, as well as animal bones and teeth, all indicative of an inclination towards artistic expression. Additionally, Garrod unearthed evidence of a sophisticated flint and bone tool industry, along with stone installations, underscoring advanced technological prowess. In 1933, during Henri Breuil’s visit to Israel, he stumbled upon the world’s first erotic sculpture at the Bethlehem market [3], portraying a man and a woman in a mating position. This complex and elaborate sculpture, when viewed from different angles, reveals various sexual aspects of the male and female bodies.

Breuil’s discovery of the statue, later identified as originating from a cave in Wadi Tekoa and dating back 15,000 years, provided empirical support for the theory that ancient cultures revered sexuality as Sacred [4], particularly within Goddess-worshipping societies that emphasized fertility. Named “The Beloved from Ein Sahari,” the sculpture now resides in the British Museum. Its fortuitous unearthing by a prominent figure like Breuil underscores the interconnectedness that permeates all existence—a network believed to emanate from the omega point by de Chardin or interpreted as the protective embrace of the Goddess over her Human offspring from an alternative perspective. This interconnected network binds not only the life stories of those who make significant historical discoveries but also the discoveries themselves.

Henri Breuil

Breuil’s explorations extended to the sorcerer’s cave in Saint-Cirq as well, revealing a figure strikingly akin to those found in the Trois-Frères cave, albeit adorned with a distinctly different head, possibly suggesting an otherworldly origin such as an alien. Dating back 15,000 years, the paintings in both caves represent some of the earliest depictions of Human figures in art. Building upon these discoveries, Breuil proposed the notion of the “horned God,” a concept that would later be further elaborated upon by Margaret Murray (see below).

Breuil’s analysis of paintings in the La Marche cave led him to assert that ancient cave dwellers possessed a level of sophistication surpassing common perceptions. The artworks depicted figures adorned with clothing, boots, and hats, alongside symbols that hinted at potential forms of ancient writing. Notably, one cave contained over 155 engraved figures, predominantly female, albeit depicted with exaggerated proportions, resembling a rhombus shape, possibly carrying symbolic significance, such as a connection to celestial bodies. Breuil posited that these cave paintings, dating back 40,000 years, attest to the artistic and spiritual acumen of early humans, centered around the female principle of creation intertwined with the forces of nature.

The discovery of carved alcoves resembling those found in Natufian culture sites in Israel, such as La Marche cave, is intriguing. This alcove system bears a resemblance to the Pleiades constellation. According to Rappengluk, one of the world’s greatest experts in Archaeo Astronomy, many of the rock niches that appear in prehistoric sites are arranged in the shape of star constellations, and he believes that they were filled with animal fat that was lit, and the fire that was created was an imitation of the stars on earth. It’s worth noting that humans are the only animals capable of seeing the stars, so the Hunter Gatherer ceremonies may have been intended to bring star energy to the earth. Some theories suggest that the drawings of deformed people on cave walls are records of aliens who came to Earth from the Pleiades.

Indeed, Breuil, along with his colleagues in prehistoric research like Pierre Thierry de Chardin and Dorothy Garrod, didn’t delve into theories involving aliens. Instead, they embraced deep spiritual concepts, sharing a devotion to their Catholic faith. Breuil and de Chardin were Jesuit priests. Their religious beliefs were intertwined with emerging Christian mystical concepts, which included various interpretations of Darwinian evolution theories. Dorothy Garrod was a believing Catholic as well.

In addition to his discoveries in the caves of France, Breuil conducted excavations at significant prehistoric sites worldwide, spanning Ethiopia, Somalia, South Africa, China, and other regions. He also held teaching positions at prominent academic institutions in France and beyond.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) was not only a philosopher and Jesuit priest but also a prominent researcher of prehistoric eras, renowned for his extensive excavations and investigations in China, where he made significant discoveries such as the Peking Man. Notably, de Chardin distinguished himself as a valiant soldier during World War I, earning the French Order of Merit, the highest military decoration for acts of heroism. It was during this conflict that he reported experiencing mystical visions and what he described as an “encounter with the absolute.”

De Chardin regarded evolution and history as a divine miracle. His basic argument was that the difference between man and other higher mammals is that a dog, for example, knows. That is, he knows where the food is, knows how to get to his house, and so on. But man is the only one who knows that he knows! He knows where the food is, but is also aware that he knows (or is hungry), and this places him in a completely different plain of awareness.

De Chardin viewed evolution and history through a lens of divine intervention, considering them to be miraculous manifestations. His fundamental argument posited that what sets humans apart from other higher mammals is their self-awareness. While a dog, for instance, may possess knowledge of where to find food and how to return home, humans uniquely possess a meta-awareness—they not only know, but they are also aware of their own knowing (or hunger), as De Chardin puts it “they know that they know”, elevating them to a distinct level of consciousness.

In a similar vein, humanity evolved over hundreds of thousands of years during prehistory, eventually reaching a point where it became conscious of its own development. This realization only dawned in the 19th century, allowing humans to observe history and prehistory from a broader perspective. They could then witness the emergence of thought, followed by the evolution of art, science, faith, values, literature, poetry, dance, music, and all the facets that define us as human beings.

The advancement of science and research enables humans to witness the marvel of evolution, from ancient human forms like Homo erectus, who possessed the knowledge to craft tools and ignite fire, to more developed forms such as the Neanderthal, who demonstrated rituals like burying the dead, and ultimately to the superior form of Homo sapiens, characterized by language and the ability to modify their environment. Today, people can observe the progression that unfolded throughout history: the advent of agriculture, the transition to settled living in houses, the establishment of cities, and the evolution of technology. Around two hundred years ago, humanity learned experienced a pivotal realization: that it was not the center of the universe with stars revolving around it, but rather a minuscule component of a vast and boundless cosmos.

This vantage point from the apex of history heightens humanity’s apprehensions about the vast expanse of space and time, compelling individuals to pursue an evolution in consciousness and aspire towards a desired future. When contemplated deeply, this expansive view of history imparts insights into the universal law of attraction, which functions across scales—from the atomic to the cosmic—and permeates the fabric of life itself. Under this law, where akin entities are drawn together, even at the level of thoughts, it is conceivable that humanity’s collective self-awareness could foster a force of attraction, resulting in a Nanosphere—a realm of interconnected thoughts encircling the Earth, akin to the biosphere.

Man reflects the world, this is the basic law and his uniqueness, and this reflection creates a center of self-awareness wrapped in ego. As the Nanosphere, the thinking atmosphere, emerges, it will lead to the shedding of the ego, symbolizing the death of the false self, and connecting to a deeper level of awareness inherent in all human beings. This transition will give rise to a collective consciousness characterized by love, ultimately serving as humanity’s redemption. However, there remains the possibility that individuals may succumb to their anxieties, leading to the ego’s destructive influence on culture and the world.

What de Chardin proposes [1] is that our present time offers a distinct viewpoint on history, enabling us to grasp the extraordinary path of evolution. This insight might provoke a sense of triviality, inciting anxiety and self-centeredness. Conversely, it could prompt us to discern the directing power throughout this voyage, kindling optimism for a hopeful future. Witnessing evolution could release forces of love which, rather than contradicting religious faiths, could actually enhance them.

The concept of the Nanosphere, or super-awareness, is more than just theoretical for de Chardin; he believed it to exist in other dimensions already. He introduced the idea of an “Omega point,” a future goal that pulls the evolutionary journey of humanity towards increasing complexity and a consciousness imbued with love. De Chardin envisioned the universe as composed of material particles and elements of love, with love’s forces drawing towards each other, ultimately transforming chaotic matter into a unified, complex entity filled with super consciousness. This evolution would usher in a new era for Earth, marked by a collective super-consciousness of love—a Nanosphere, envisioned as a thinking layer or a soulful atmosphere, signifying the divine’s presence.

De Chardin linked the concept of the Omega point to the archetype of Jesus, depicting him as a Divine Human who invites humanity to surpass the ego—encouraging a metaphorical death and resurrection to become part of the collective human consciousness. However, his significant work, “Human Consciousness,” which explores the relationship between evolution and the development of consciousness using Darwinian principles, sparked controversy within the Church. As a result, he was at risk of excommunication from the Jesuit order he was part of and faced restrictions on spreading his spiritual teachings and publishing his works.

De Chardin was committed to staying within the Catholic Church, thus he set aside his writings to focus on his work in science and archaeology. After his passing, his essays were released, leading to a shift in perception towards him. He became recognized within the core of Catholicism, even receiving accolades as a modern Catholic theologian who effectively merged science with faith. Popes like Benedict XVI and Francis have acknowledged and welcomed his ideas.

De Chardin embarked on his global research expeditions fueled by a missionary-like enthusiasm, not with the aim of converting others to a different religion, but to enhance our collective understanding of human development, allowing us to appreciate our essence and the marvel of evolution. He devoted his life to this mission, embracing celibacy (in his monastic life) and residing in foreign countries. In return, he viewed himself as a member of a broader family—the human family, bound together by God’s love. He formed numerous friendships, considering these individuals as siblings, and academic and spiritual partners who resonated with his perspective. Among his friends was Dorothy Garrod, known for her significant archaeological work in Israel.

Dorothy Garrod and de Chardin first crossed paths at the Institute of Paleontology in Paris in 1922. At the time, Garrod was 30, embarking on her academic journey in prehistory under Henri Breuil’s mentorship, and newly committed to her Catholic faith. De Chardin, about a decade her senior, had just completed his doctoral degree in geology and was deeply engaged in developing his religious philosophy. Following the upheaval of the First World War, which profoundly impacted their perspectives on the world, they came to believe that humanity faced a critical choice between self-destruction and spiritual evolution. Together, they viewed their work as vital to illuminating the extraordinary journey of human evolution from animalistic origins to conscious beings. They harbored the hope that understanding the marvel of humanity could awaken the human race to pursue a path of evolution characterized by love and consciousness.

De Chardin’s spiritual concepts about the intertwining of spirit and matter, along with the notion that observing evolution could be a pathway to the spirit’s emancipation from matter and a rise in human consciousness, led him to view himself as a participant in a collective human endeavor to elevate awareness and consciousness towards a new spiritual era. He identified his most significant contribution to this effort in the realm of prehistoric research, a field in which he excelled. De Chardin believed that adopting a higher perspective on evolution would enable humanity to comprehend its identity and direction. However, to achieve this understanding, he argued that more pieces of the “puzzle” were needed, and thus considered it his mission to uncover them.

De Chardin’s concepts on the significance of their field resonated with many of his contemporaries, including Dorothy Garrod and likely Henri Breuil, influencing their perception of the work they were engaged in. These ideas provided an explanation for their deep fascination and love for the study of history, imbuing their endeavors with purpose. In essence, viewing human history merely as a collection of disjointed events renders its study a matter of mere intellectual curiosity. However, recognizing a coherent thread of development and progress transforms the exploration of the past into a tool for shaping the future. This perspective, shared by de Chardin, Garrod, and possibly Breuil, underscored their belief in the transformative power of uncovering human history.

Margaret Murray

Margaret Murray (1863-1963) is recognized for her significant contributions as an archaeologist, particularly for her excavations in the Land of Israel. Beyond her archaeological achievements, she was also deeply involved in witchcraft, even leading the British association of witches. Her unique dual identity as both a respected archaeologist and a prominent figure in witchcraft highlights a fascinating blend of scientific inquiry and esoteric practices. Margaret was indeed a witch, in the most positive sense of the word, embodying a unique blend of scholarly insight and mystical tradition. It’s speculated that her archaeological pursuits in these historic regions might have been driven by an interest in uncovering evidence of ancient Goddess worship, aligning with her broader interests in the mystical and the historical intersections of religious practices.

Margaret, born into an Anglo-Indian family, was deeply knowledgeable in Indian, Egyptian, and Celtic cultures. She made history as the first woman to be appointed as a lecturer in archaeology at universities in England, showcasing her expertise in ancient civilizations. Beyond her academic and intellectual pursuits, Margaret was a prominent feminist, contributing significantly to both archaeology, through active excavations, and folklore, serving as the head of the English Folklore Society.

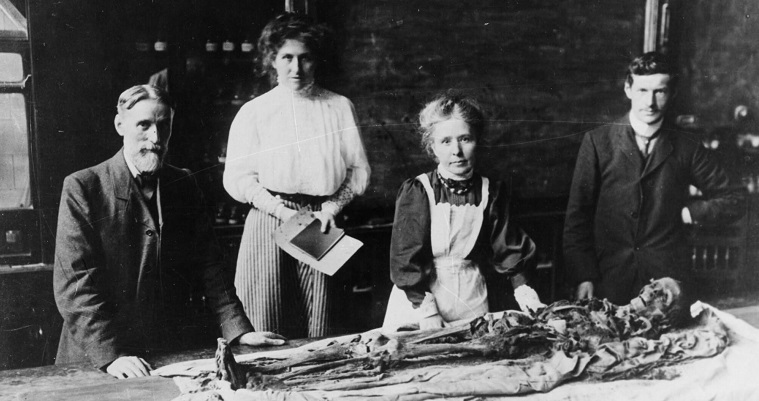

Murray’s archaeological journey commenced alongside the renowned Flinders Petrie, often hailed as the father of archaeology. Working as his first assistant, they uncovered significant sites in Egypt, including the cemetery at Sakkara and the Osirion at Abydos. Branching out on her own, Murray’s work led her to the islands of Majorca and Menorca in Spain, where she unearthed previously unknown prehistoric cultures through their remarkable Megalithic sites. Beyond her fieldwork, Murray was also an avid lecturer, sharing her knowledge at various institutions. Her scholarly achievements were recognized with a doctorate from the University of London’s UCL, marking her as a prominent figure in the academic and archaeological community.

During World War I, Murray began formulating a groundbreaking theory positing the existence of a widespread prehistoric religion centered around a deity she termed the Horned God. This theory suggested that across various regions of the world, from the Pamir Mountains in Central Asia to the Vinča culture along the Danube, there was a veneration of horns, symbolizing the raw power of nature. According to Murray, this ancient religion revered fertility and femininity, aspects that persisted into the Middle Ages in Europe, manifesting in popular folklore and the practices of witchcraft. Her work implied that these remnants were evidence of a continuous thread of spiritual and religious practice, highlighting the Horned God as a universal symbol within the “old religion.”

In the latter part of her remarkable life, spanning over a century, Murray dedicated herself to exploring and substantiating her theories on witchcraft. She made significant contributions to the field, notably authoring the entry on “witchcraft” for the British encyclopedia, which has had a lasting impact on how we understand the subject. Murray posited that the “old religion” she described was a universal belief system spanning the human race from the early Stone Age, a time when humans were hunter-gatherers living in caves. She identified the Horned God as a key deity of this era, evidenced by cave wall paintings and burial offerings, likely drawing inspiration from the work of Henri Breuil. Murray argued that this ancient religion faded with the advent of the agricultural revolution, which saw a shift towards vegetation deities and the emergence of a Goddess-Mother figure. However, she believed that traces of the old religion re-emerged with the urban revolution, marking the dawn of recorded history in civilizations such as Sumer and Egypt.

Murray interpreted the presence of horned deities in ancient Sumerian and Egyptian pantheons as a continuation of the veneration of the ancient Horned God, suggesting that the underlying beliefs associated with these figures persisted in secluded communities into the late Middle Ages in Europe. She theorized that the widespread persecution of witches during the Middle Ages was not merely a crackdown on heresy but a targeted effort to eradicate the remnants of this old religion that lingered among rural populations, particularly among women. Witchcraft, in her view, was a direct descendant of this ancient worship centered around the Horned God. Consequently, the church demonized this deity, transforming him into the devil, and persecuted its adherents, often leading to executions at the stake. Murray’s theories proposed a direct link between prehistoric religious practices and the witch hunts of the medieval period, framing them as a clash between ancient traditions and the rising dominance of the Christian church.

In 1933, Margaret Murray published “The God of the Witches,” [1] a work aimed at the general public where she elaborated on her theory of the “old religion.” Through this book, she endeavored to reconstruct the ancient religion using evidence from medieval witch trials, a methodology that led to significant academic critique. Beyond her exploration of witchcraft, Murray also authored works on a variety of other subjects. These included “Ancient Egyptian Religious Poetry” and “The Splendour that was Egypt,” showcasing her broad expertise in ancient cultures. Additionally, she delved further into witchcraft studies with her publication “The Witch-Cult in Western Europe,” further establishing her as a pivotal figure in the study of both archaeology and the history of witchcraft.

Margaret Murray dedicated two archaeological seasons to excavations in Israel, where she was part of the team that excavated Tel Ajul (near Gaza) alongside Flinders Petrie in 1935 and 1936. Following this, she undertook independent excavations in Petra in 1937, an endeavor that culminated in the publication of a book about the site. Her interest in Petra might be linked to its status as a sacred place, potentially connected to the worship of the Goddess and possibly the “Horned God,” suggesting a continuation of her research into ancient religions. While the specific reasons for her excavation at Tel Ajul remain unclear, the participation of Gerald Gardner, the founder of the modern Wicca movement, as a volunteer in these excavations is noteworthy. Gardner was profoundly influenced by Murray’s works, indicating a significant intersection between archaeological exploration and the revival of witchcraft practices in the modern era.

At the impressive age of 91, in 1953, Margaret Murray assumed the role of president of the British Folklore Society, a position she maintained for a decade. Her influence extended far beyond her academic and archaeological achievements, reaching into the burgeoning neo-pagan and witchcraft communities in Britain. Following the decriminalization of witchcraft after the 1940s, new orders and movements emerged, many of which revered Murray not just for her scholarly work but also for her alleged clandestine role as the head of the British Association of Witches. Regardless of the veracity of these claims, it’s clear that her publications, particularly those exploring the historical presence of witchcraft, significantly shaped the beliefs and practices of the Wicca movement. This modern witchcraft tradition drew heavily upon Murray’s theories and works.

How to be a good Witch?

Margaret Murray suggested that the rituals of the “Old Religion” were characterized by dancing and singing, activities in which women particularly excelled. She pointed to Paleolithic cave paintings as evidence, highlighting a specific depiction of nine women dancing around a male figure. Murray interpreted this scene as a representation of a witchcraft ritual, with the male figure symbolizing the Horned God. This interpretation extends to her understanding of medieval witchcraft practices, where she described “witches” as being organized into groups known as Covens. Within these groups, a sorcerer, embodying the Horned God, assumed the role of the “Grand Master.”

Besides the domestic familiar, each witch also had a divine familiar, typically a larger animal like a horse or deer, or a substantial bird such as a crow or dove. This divine familiar aided in prophetic tasks, including foretelling the future by analyzing its behavior or movements. If a suitable animal for the divine familiar was not available, then cloud formations could be used for divination. Witches were adept at summoning rain and storms, altering the weather, and possessed magic words that enabled them to transform themselves into animals.

Among magical artifacts, the cauldron and bowl held paramount importance, elucidating the discovery of a bowl fragment in a witch’s cave at Nahal Hilazon, believed to have been utilized in witchcraft. At times, the cauldron or bowl’s contents were poured out, with the resulting vapors dispersing their influence, or the liquid within was splashed outward. Murray articulated a distinction between magic and religion: magic involves exerting control over forces, whereas religion entails submission to a higher power. In her explorations of witchcraft, she differentiated between ritualistic witchcraft, aligned with nature’s cycles and posited as the primeval religion of cave dwellers, and practical witchcraft, which she regarded as devoid of value and recommended avoiding.

While one might question Murray’s theories, it seems crucial for understanding the spiritual life of ancient humans—from cave dwellers to early farmers—to adopt their viewpoint and explore the realms of witchcraft, shamanic rituals, and magic. This perspective encourages a compassionate and engaging approach, aiming for a profound comprehension of these practices and their links to human psychology, personal experiences, and the essence of humanity. Rather than reducing these practices to mere superstitions, it suggests that a deeper exploration can reveal their significance and place in human history.

[1] According to Ellie Schiller, many of Israel’s female researchers had no family: – Barkay, Gabriel, Schiller, Eli, Barkay, Gabriel and Schiller, Eli (2013). Following the first explorers of the Land of Israel / written and edited by Eli Shiler and Gabriel Barkai. Ariel; 209.

[2] [2] Garrod, D. A. & Bate, D. 1 937 The Stone Age of Mount Carmel, I.

[3] Together with Rene Neville (1899-1952), a prehistorian who worked in Israel and also the French consul.

[4] And on this occasion it is worth mentioning that another description of an ancient sexual intercourse appears in a rock painting in Kilwa in Jordan, attributed to the Neolithic period (the time of the Goddess culture).

[1] De Chardin, P. T. (2018). The phenomenon of man. Lulu Press, Inc.

[1] Murray, M. A. (1970). The God of the witches (Vol. 332). Oxford University Press on Demand