This article discusses the Via Palma pilgrimage route, detailing Day 14’s journey from Jerusalem to Bethlehem and back, and Day 15’s trek from Jerusalem through the Judean Desert to Jericho, highlighting desert monasteries and the Good Samaritan site.

The 14th day: Bethlehem

On the 14th day of the “Via Palma” pilgrimage, the focus was Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus. The pilgrims would walk the 10 km journey from Jerusalem, a trek lasting two to three hours. Midway, a stop at “The Field of Flowers” near Ramat Rachel and the Mar Elias Monastery offered a moment of reflection, where tradition holds that individuals receive rewards for their good deeds. This belief mirrors the Christian artistic symbolism where a bouquet of flowers represents the good deeds that lead one to heaven, and the area’s remarkable bloom likely inspired this tradition.

The journey continued to the Mar Elias Monastery, established during the Byzantine era and rebuilt by the Crusaders in the mid-12th century. Legends recount this as the resting place for Mary on her journey from Galilee to Bethlehem during her ninth month of pregnancy. The census of the Roman Empire necessitated this journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem. Originally, during the Byzantine period, the church known as “The Kathysma” stood a hundred meters away from today’s monastery. It was a large octagonal building housing the rock on which Mary rested, but by the time of the “Via Palma,” this tradition had shifted to the Mar Elias Monastery.

Upon reaching the outskirts of Bethlehem, pilgrims made a visit to Rachel’s Tomb. Descriptions from the 12th century, such as those by Benjamin of Tudela, mention an altar comprised of 12 stones representing Jacob’s 12 sons (and the tribes of Israel), deeply moving the pilgrims. Rachel is seen as a precursor to Mary, with all holy women in the Bible, especially the four matriarchs, considered prefigurations of Mary. The verses from the book of Jeremiah, describing Rachel mourning for her sons who were exiled, were interpreted by pilgrims as a prophecy foreshadowing Herod’s massacre of Bethlehem’s infants following Jesus’ birth.

The pilgrimage’s emotional climax was reached at the Church of the Nativity, the site of Jesus’ birth and the beginning of the redemption and divine revelation process. The first Crusader kings were crowned here, making it a centerpiece for Christmas celebrations familiar to the pilgrims. Jesus’ humanity was fully realized at the moment of his birth, symbolizing hope for believers. This miraculous birth was viewed not just as a singular historical event, but as a continual demonstration of God’s care for humanity.

As the “Via Palma” pilgrims made their way into Bethlehem, they might have felt akin to the three Magi, who followed a star to visit the newborn Jesus with gifts, or resembled the shepherds in the fields who were visited by an angel announcing the birth of the Savior. Their journey often began with a visit to the Shepherd’s Field, located 2 km from Bethlehem, before proceeding in a manner that mirrored these historical events to the Church of the Nativity.

The Church of the Nativity itself stands as a remarkable edifice, originally constructed in the 4th century AD by Empress Helena alongside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and later refurbished into its current form (which largely remains today) in the 6th century by Emperor Justinian. It is among the oldest continuously active Christian churches, having remained in Christian hands even after Jerusalem’s conquest by Muslims. Bethlehem, with its substantial and welcoming Christian community, has been deemed an essential and significant stop on the pilgrimage route, echoing the deep historical and spiritual connections pilgrims seek on their journey.

The Church of the Nativity’s central section is a vast basilica, stretching 50 meters in length, segmented into five aisles and supported by 48 large columns. At its eastern end, an apse leads down to the cave identified as Jesus’ birthplace, marked distinctly by a fourteen-pointed silver star. This star symbolizes the fourteen generations from Abraham to David, from David to the Babylonian exile, and thence to Jesus. Adjacent to this sacred cave is a smaller grotto, believed to be where the infant Jesus was laid in a manger. This site, visited by the Magi and shepherds guided by divine revelation, now welcomes pilgrims eager to connect with this pivotal moment in Christian faith.

In the era of the Crusaders, a new church and monastery dedicated to Saint Catherine were constructed beside the Church of the Nativity. This site commemorates the vision in which Jesus foretold Catherine of Alexandria’s martyrdom. Despite historical indications that Catherine never visited Bethlehem, pilgrims regard her as a symbolic figure from the East, allowing her apparition’s location to be set in Bethlehem. This city, known for its scholarly heritage, was home to Saint Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin, and Paula of Rome, a noblewoman turned nun, in the late 4th and early 5th centuries, underscoring Bethlehem’s significance as a center of Christian learning and spirituality.

Christmas ceremonies are celebrated at the Saint Catherine Monastery, drawing a parallel to the Easter ceremonies at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This juxtaposition reflects a profound duality between Bethlehem and Jerusalem: Bethlehem as the site of birth, and Jerusalem as the site of death and resurrection. Approximately 200 meters east of the Church of the Nativity lies the Milk Grotto, where the Holy Family is said to have taken refuge from Herod’s soldiers. Legend has it that a drop of Mary’s milk spilled onto the cave’s floor, turning its walls white and imbuing them with miraculous qualities.

The concept of Mary’s milk, emblematic of Jesus’ humanity, gained prominence in the 12th century, influenced by the visions of Bernard of Clairvaux. It came to be seen as a divine nourishment, akin to ambrosia, facilitating spiritual growth and sustenance. Mary’s milk, juxtaposed with Jesus’ blood, represents a transformation of Mary’s blood into the milk that fed Jesus, symbolizing a transference of divinity to believers. This notion underscores the intimate connection between the physical and spiritual in Christian theology.

According to legend, in the year 1146, Bernard of Clairvaux experienced a profound moment of divine revelation. While kneeling before an image of Mary nursing Jesus, he prayed fervently. To his astonishment, the baby ceased suckling, and Mary turned towards him, splashing drops of milk onto his lips. This sacred milk, which had nourished Jesus, infused Bernard with spiritual enlightenment and understanding. Symbolically, it represented the potential for every individual to partake in divine grace by drawing from this sacred source.

This encounter imbued Bernard with profound insight, leading him to recognize Mary as the universal mother of humanity, not solely of Jesus. He eloquently conveyed this revelation through a series of hymns praising Mary, immortalized in his book of devotions. For pilgrims, familiar with this legend, visiting the Milk Grotto brought this sacred narrative to life. Moreover, for female pilgrims, it held the promise of healing fertility issues, further enriching the spiritual significance of the site.

Geographically, the pilgrimage journey to Jerusalem extended beyond the city itself. The trek to Bethlehem unveiled a distinct landscape, evoking the ancient Kingdom of Judah. Some pilgrims, continuing their exploration, ventured onwards to Hebron, the city of the patriarchs, pausing at significant sites like Alonei Mamre, associated with Abraham’s encounter with three angels. Others opted for a return route to Jerusalem, with a detour to the Monastery of the Cross, renowned for its connection to the origins of the true cross.

For today’s itinerary, I recommend departing from the Old City of Jerusalem towards Bethlehem via Hebron Road. Along the way, pilgrims can pause at the Katisma site, now an open field, and the Mar Elias Monastery. Upon reaching Bethlehem, key sites to visit include Rachel’s Tomb and the Church of the Nativity, alongside other Christian landmarks. Optional extensions may include a visit to the shepherds’ field and its accompanying church. On the return journey, pilgrims can explore new Jewish neighborhoods, winding their way towards the Valley of the Cross Church before concluding their route back in the Old City.

Mr. Saba monastery

ocated about three hours’ walk east of Bethlehem, perched on a cliff overlooking the Kidron Wadi, stands the largest and most significant monastery in the Judean Desert. This Greek Orthodox monastery held immense importance as it served as the epicenter of the desert monastic movement. The Typicon, the book of laws governing all monasteries, was written by the monastery’s founder, St. Sabbas. It boasted a substantial library and housed religious treasures such as icons and sacred artifacts.

During the Crusader period, the monastery hosted notable figures like the 13th-century Serbian saint, St. Sava. Renowned as one of the most important theologians and administrators of his time, St. Sava received the staff and name of the monastery’s founder, St. Sabbas, who lived in the 6th century. St. Sava played a pivotal role in founding the Serbian Church and is revered as the “Father” of the Serbs.

This historical account highlights the collaborative nature of pilgrimage to the Holy Land, where individuals from various Christian denominations participated. Even the Crusade Queen Melisinda of Jerusalem contributed to the monastery’s upkeep, emphasizing the shared reverence for sacred sites across different faiths. Despite changes in rulership and conquests, the monastery remained untouched and continued to serve as a thriving pilgrimage destination, a status it retains to this day.

The 15th day: from Jerusalem to Jericho

The destination of the pilgrimage on the “Via Palma” was Jerusalem, but the journey did not end there. After arriving in Jerusalem, the pilgrims devoted a few days to discovering and experiencing it. Similarly to pilgrimages to Rome or Santiago de Compostela, the journey continued beyond the destination. For pilgrims on the “Via Palma,” this meant traveling to the place of Baptism in the Jordan River, not far from the Dead Sea. Here, they sought to be baptized where Jesus was baptized, symbolizing rebirth and receiving a palm tree leaf as a token of victory over death and the completion of their journey.

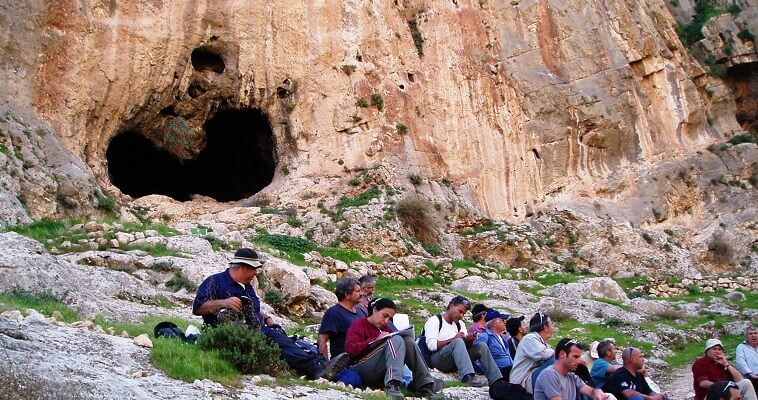

On the 15th day of the pilgrimage, the journey took the pilgrims from Jerusalem to Jericho, leading them through the stark beauty of the Judean desert. Along the way, they visited renowned desert monasteries, sanctified by the lives of saints such as John the Baptist and ancient prophets. For many, it was their first encounter with a desert landscape, devoid of vegetation and characterized by hues of brown and yellow. This unfamiliar terrain, devoid of European equivalents, surely struck them as a testament to God’s grandeur.

Their first stop was the esteemed monastery of Euthymios in the industrial area of Ma’ale Adummim, serving as the epicenter of the Judean desert monastic movement. Pilgrims descended from the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem to Mishor Adummim (Adummim Plateau), passing by the Martyrius Monastery nestled within the Ma’ale Adumim neighborhood. Alternatively, some chose a longer but more picturesque route through the Wadi Kelt gorge, where they encountered the Hariton Monastery near the springs feeding the Wadi Kelt stream (Ein Perat).

After departing from the monastery of Euthymius, the pilgrims journeyed a few kilometers amidst the hills to reach the Good Samaritan Inn, situated halfway between Jericho and Jerusalem. Here, a Templar fortress once stood, offering protection to pilgrims, followed by a Muslim khan. From the Good Samaritan Inn, they ventured into the gorge of Wadi Kelt, believed to be Chorath brook, where Prophet Elijah sought refuge in a cave and was sustained by ravens. It was also where Joachim, Mary’s father, awaited her arrival in a cave.

The Wadi Kelt canyon, a picturesque desert oasis, features a meandering stream that eventually reaches Jericho, with the towering Mount Quruntul (Mount of Temptation) overlooking the city. Jericho served as an ideal resting place for the night, offering respite amidst its historical significance and natural beauty.

Euthymius Monastery in Adummim Plateau

Euthymius, regarded as the Father of the Judean desert monastic movement in the 5th century, was mentored by Hariton, the founder of the first monastery in the nearby Wadi Kelt. Noteworthy disciples of Hariton included influential figures like St. Sabbas, Martyrius, and Gerasimus, each leaving their mark on Judean Desert monasticism.

Born in 377 into a noble family in Militana, Cappadocia, Turkey, Euthymius (D. 473) was immersed in the church from a young age. Ordained as a priest later in life, he assumed responsibility for the monks within his city’s jurisdiction. At 29, he embarked on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and chose to live as a hermit in the nearby desert. In 405, Euthymius arrived at the Laura of Hariton in Wadi Kelt, commencing his monastic journey in the desert. During his time there, he formed a close bond with Theoctistus of Palestine, embarking on annual 40-day fasting journeys into the desert depths before Easter. This tradition of extended desert sojourns, initiated by Euthymius and Theoctistus, greatly influenced the trajectory of the monastic movement.

During one of their journeys, Euthymius and Theoctistus arrived at Nahal Og, where they established the first Cenobitic monastery in the Judean desert, naming it “Theoctistus Monastery” in honor of Euthymius’ friend. Following the monastery’s founding, Euthymius ventured to Masada, dwelling there in solitude for a period before relocating to the outskirts of the Ziph desert near Hebron. Here, he established another Coenobium monastery, fostering strong connections with the surrounding tribesmen.

Ultimately, Euthymius settled on the Adummim plateau, where he erected his third and most significant monastery, known as the “Euthymius Monastery.” Initially a laura—a place for solitary monks who convene only weekly—Euthymius, on his deathbed, decreed that the monastery be transformed into a Coenobium. This transition occurred in 478, five years after his passing, with his disciple Martyrius appointed as the Patriarch of Jerusalem. The monastery’s construction spanned three years, resulting in the building that stands today. Euthymius was laid to rest within the monastery grounds.

The Euthymius Monastery played a pivotal role in the Christianization of the Arab tribes in the Judean Desert region. Legend has it that Euthymius miraculously healed the son of a local tribal chief, prompting the pagan Arab tribes to embrace Christianity. These tribes remained steadfastly loyal to Euthymius until his passing. Following the monastery’s construction, many tribesmen settled nearby, forming a community closely intertwined with the monastery.

Notably, the Euthymius Monastery served as a launchpad for numerous monks who ascended to prominent positions within the ecclesiastical hierarchy of the Land of Israel. Located in close proximity to Jerusalem, the monastery facilitated the integration of its monks into the city’s leadership. This marked a seminal moment in the history of the monastic movement, transitioning from individualistic desert retreats to organized and influential involvement in both religious and secular affairs. Henceforth, the desert monks became recognized figures, earning esteem from ecclesiastical and secular authorities alike.

Empress Aelia Eudocia emerges as a notable figure in the annals of monasticism in the Judean Desert, particularly in relation to Euthymius. Ascending to the throne in 421 upon her marriage to Theodosius II, she left an indelible mark on Jerusalem’s landscape. Her initial visit to Jerusalem in 438 was followed by a more prolonged stay in 442 until her passing in 460 AD. Eudocia held Euthymius in high regard, demonstrating her admiration through various acts of patronage. She erected a tower for him atop Jabel Montar and commissioned the construction of a water reservoir and church near his monastery, situated in an area known as “Kazer Ali.”

Throughout his tenure, Euthymius found himself embroiled in the theological disputes between the Monophysites and the Orthodox factions. Unwavering in his support for the Orthodox stance, he weathered a temporary exile from his monastery lasting two years. However, with the triumph of the Orthodox position at the Chalcedon conference, Euthymius returned to his abode, fortified in his resolve, and witnessed his monastery’s ascent to the pinnacle of its influence.

In 457, Euthymius welcomed Sabbas into the monastery, alongside Martyrius and Elias from Nitria in Egypt. This trio would go on to establish their own influential monasteries. Sabbas founded the renowned Mar Saba Monastery, becoming a towering figure in desert monasticism. Martyrius, on the other hand, established the Martyrios Monastery in Ma’ale Adummim, eventually ascending to the position of Patriarch of Jerusalem. Another disciple, Gerasimus, founded a monastery in the plains of Jericho, laying the groundwork for the monastic movement in the Jordan Valley.

Euthymius passed away in 473 at the remarkable age of 97. Even in his final days, he was described by Cyril of Scythopolis as a luminous figure: “His appearance resembled that of an angel, his demeanor was serene, and his strides were graceful. Despite his age, his countenance remained radiant, his eyes keen, his stature diminutive, yet his beard, full and white, cascaded down to his stomach. Remarkably, he retained his vitality until the end, with his faculties unimpaired by the passage of time.”

At the time of the “Via Palma” pilgrimage, the Euthymius Monastery likely remained active, offering pilgrims a place to rest on their journey to Jericho, as documented by pilgrim accounts like that of Father Daniel in 1106. However, by the 14th century, the monastery fell into disuse and was replaced by a road khan. Another khan, known as the “Red Khan,” was subsequently erected to accommodate the influx of pilgrims.

Situated a two-hour walk from Jerusalem, the Euthymius Monastery served as a pivotal stop along the pilgrimage route. From there, the journey continued for an additional hour to the Good Samaritan Inn. Along this path lies the route traversed by Jesus as a child during his annual pilgrimage to the Jerusalem temple at Passover, a journey that culminated in one of the most poignant stories of the New Testament.

The Good Samaritan

In the middle of the road between Jericho and Jerusalem, nestled within a narrow pass through the hills, stands a Khan (road inn) dating back to the Byzantine period. This site has been identified as the setting for the parable of the Good Samaritan in the New Testament, as described in the scriptures: “In reply Jesus said: “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead. A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan, as he travelled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him” (Luke, 10:30-34).

The Byzantines erected a sizable church adjacent to the Khan, but it fell into ruin. The Crusaders reconstructed a citadel atop the nearby hill, dubbed the “Red Citadel” due to the crimson-hued rocks. This fortress was overseen by the Knights Templar. Subsequent rulers, including the Mamluks and Ottomans, maintained the site as a road khan and fortress. This persisted until the Six-Day War, after which the location underwent a transformation. The Antiquities Authority, in collaboration with the Civil Administration in Judea and Samaria and the Ministry of Tourism, embarked on an ambitious project to establish a mosaic museum, the sole one of its kind in the country. This museum showcases mosaics sourced from across the West Bank, including rare specimens from the Byzantine era depicting scenes of Samaritan life. Today, this site offers a breathtaking visitor experience, featuring not only mosaics but also ancient residential caves from the Second Temple period, remnants of churches, archaeological artifacts, and captivating viewpoints.

From the Good Samaritan site, we’ll trek approximately two kilometers along the main road towards Mitzpe Jericho. Just before reaching the settlement, a road veers northeast toward the Monastery of St. George in Wadi Kelt. This route, offering a shorter path to Jericho, includes a stopover to admire the stunning St. George Monastery.

However, for those keen on exploring additional sites and desert monasteries en route to Jericho and capable of tackling a longer journey, an alternative route awaits. They can backtrack from the Good Samaritan site to Kfar Adummim and then navigate the desert roads to the Hariton Monastery near the Ein Perat water springs in Wadi Kelt. From there, they can proceed along the wadi to Ein Maboa, another notable water spring and pool. Following the water canal leads them to St. George’s Monastery, where they can reconnect with the shorter route towards Jericho.

According to Origen, an influential Christian thinker from the 3rd century AD, the story of the Good Samaritan serves as an allegory for the spiritual journey. In this interpretation, Jerusalem represents the realm of spirituality (the high), while Jericho symbolizes materiality (the low). The man descending from Jerusalem to Jericho mirrors the descent of the soul from heaven to the earthly realm, wounded by original sin and in need of redemption. Jesus, portrayed as the Good Samaritan, intervenes to save the wounded soul, symbolically pouring oil and wine on its wounds. Despite Jericho representing the realm of matter in Origen’s allegory, our journey continues towards it.

Hariton Monastery

A few kilometers north of the Euthymius Monastery, nestled in the gorge of Wadi Kelt near the first significant spring, Ein Perat, lies the Hariton Monastery. Founded by the monk Hariton at the end of the 4th century AD, it marks the inception of the Judean Desert monasteries and is associated with the emergence of the Monatic movement in the Land of Israel. Accessible via the road from the settlement of Almon or through desert paths, the trail from the Ein Perat Reserve, where the monastery resides, stretches for 21 kilometers to Jericho. The path follows an aqueduct supplying water year-round, passing by several springs along the way. Ein Perat itself boasts pools, waterfalls, aquatic vegetation, and a unique desert landscape.

Hariton hailed from a noble family in the city of Konya, Turkey. Following the end of religious persecution against Christians around 312 AD, he embarked on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, aspiring to emulate the ascetic lifestyles of Elijah and John the Baptist in the desert. However, his journey took a perilous turn when he fell into the hands of robbers near Jerusalem. They imprisoned him in their cave, intending to kill him later. Yet, through a miraculous intervention, Hariton was spared. A poisonous snake crept into the cave, contaminating the robbers’ wine jug with venom. Upon consuming the tainted wine, the robbers perished, while Hariton managed to free himself from his chains. He inherited the robbers’ treasures and generously distributed a portion to hermit monks dwelling near the Jordan River’s estuary into the Dead Sea. With the remaining resources, he established the first monastery in the Judean desert, atop the cliff overlooking Ein Perat, at the very site of the robbers’ cave. Thus, the legacy of the Judean Desert monastic movement began.

Hariton introduced a novel form of monasticism known as the Laura (or Lavra), which deviated from the conventional practices of Cenobitic monasticism, where monks lived collectively, or Eremitic monasticism, where monks lived in complete isolation. In the Laura, monks resided individually in their cells for most of the week, engaging in solitary contemplation and work. However, on Saturdays and Sundays, they convened for communal prayer in the monastery’s church, presided over by a priest. During these gatherings, they also replenished their supplies of food and raw materials necessary for their solitary pursuits throughout the week. The term “Laura” derives from the Greek word for “narrow path,” alluding to the winding paths that connected the isolated cells with the central church and other monastery buildings.

In Byzantine society, reclusive monks were revered as holy figures and admired for their perceived closeness to God, achieved through their dedicated lives of celibacy and seclusion. This intimacy with the divine was believed to grant them the ability to perform miracles. Hariton’s renown quickly spread throughout the region, attracting many followers to his monastery. He provided his disciples with laws and regulations governing their new monastic lifestyle, including directives to be content with a single meal at the end of the day consisting of bread, salt, and water. Additionally, he established a daily routine of seven fixed prayer times and instructed them to engage in manual labor, such as basket weaving or rope making, in their cells during the week. Throughout these activities, the monks were encouraged to maintain a continuous state of prayer and recitation of the Psalms.

Hariton emphasized the importance of prayer and recitation of Psalms seven times a day, at fixed intervals, urging monks to approach these practices with deep intentionality. He particularly stressed the significance of rising for the night prayer, mandating that monks remain awake for six hours each night—a tradition that continues to be upheld today. Hariton encouraged monks to commit passages of the Psalms to memory and to engage in this practice between prayer sessions and during their work. Additionally, he advised them to study the Holy Scriptures whenever possible. One of his key directives involved the obligation to welcome guests and provide assistance to the poor, promoting social engagement among the hermits of the Judean Desert—a departure from the solitary practices observed by Egyptian hermits.

As the number of monks in the Laura of Wadi Kelt, known as “Laura Pharan,” continued to grow, Hariton decided to seek a new place of solitude. He journeyed along Wadi Kelt until he arrived at a cave nestled in the cliffs above Jericho, where he established the Quruntul Monastery, the site where Jesus was tempted by Satan. Subsequently, as the Quruntul Monastery gained renown and became overcrowded, Hariton relocated to Nahal Tekoa, now known as Wadi Hariton, where he founded the ancient Laura, also known as the “hariton Monastery.” In the final chapter of his life, he retreated to a cave nestled in a nearby cliff, where he lived alone in his cell until his passing.

Hariton’s dedication to solitude and spiritual growth is evident in his choice to establish his residence in the remote and elevated cave known as “the cave of The Holy Engraving.” Despite his advanced age and physical frailty, he continued his ascetic practices, relying on divine intervention to provide for his needs. His prayer for water resulted in the miraculous emergence of a clear and cold spring, a testament to his deep faith and connection with the divine.

Hariton’s influence extended far beyond his own lifetime, as he initiated a movement of monasticism in the Judean Desert that flourished for centuries. At its peak, this movement saw the establishment of over fifty monasteries and attracted thousands of monks seeking spiritual enlightenment. Although the influence of Byzantine rule waned over time, the monastic tradition experienced periods of revival, particularly during the Crusades. Today, only four active monasteries remain in the Judean Desert, with two of them founded by Hariton himself—one in Ein Perat and the other in Quruntul. The caves of solitary monks above Ein Perat stand as a testament to the enduring legacy of Hariton and the monastic movement he inspired.

During the Crusades, it’s likely that Pharan Monastery wasn’t fully active, although individual monks may have still inhabited the area, and Hariton’s cave likely remained a prominent pilgrimage site. For travelers bound for Jericho, an alternative route through the Wadi Kelt gorge provided a scenic and refreshing journey compared to the arid desert plateau to the south. Despite being slightly longer due to the canyon’s winding path, this route offered abundant water, shade, and vegetation, captivating pilgrims with its natural beauty.

Pilgrims, particularly those unfamiliar with desert landscapes, were undoubtedly awed by the lush surroundings of Wadi Kelt, making it a memorable aspect of their journey. It’s conceivable that pilgrims chose different routes for their onward and return journeys, allowing them to fully explore the diverse landscapes and sacred sites of the region. This approach enabled pilgrims to not only visit the baptism site in the Jordan but also to experience the spiritual significance of the Good Samaritan sites and the Desert Monasteries, all while savoring the enchanting allure of Wadi Kelt Canyon.

St George’s Monastery

From the Hariton Monastery, travelers can embark on a scenic journey along Wadi Kelt towards the St. George Monastery. However, for those following the main road from Jerusalem to the Euthymius Monastery and onwards to the Good Samaritan Inn, a recommended detour awaits. Approximately 2 kilometers along the main road towards Mitzpe Jericho, just before the settlement, a left turn leads to a landscape road guiding travelers to the St. George Monastery in Wadi Kelt, and eventually to Jericho.

Nestled amidst the cliffs above Wadi Kelt, the St. George Monastery remains active to this day. Perched a few kilometers west of the canyon’s exit near Jericho, the monastery boasts isolated hermit caves accessible only by ladder. Above the cliffs, crosses installed by the monks adorn the desert landscape. A paved road leads to a parking lot, offering access to a breathtaking vantage point on the canyon’s opposite side. Additionally, a winding walking path descends into the canyon, crosses it, and ascends to the monastery—a short yet steep journey well worth the effort.

In the late 5th century, a group of Syrian monks, accompanied by an Egyptian monk named George of Choziba, arrived at this enchanting location. Dedicated to the principles of Syrian monasticism, which emphasize the purification of the heart through celibacy and contemplation, these monks aspired to transcend earthly limitations. Their ultimate goal was to attain angelic purity while still in the flesh, seeking to awaken the spiritual essence within themselves. This transformative journey, later termed “theosis,” aimed at a profound union with the divine, echoing the spiritual evolution of figures like the prophet Elijah. Renowned for his attainment of eternal life and the profound revelation found in silence, Elijah served as a revered model for these monks’ spiritual endeavors.

read the article on the – Carmelite Order.

According to their belief, Elijah sought seclusion within a cave in the wadi, which corresponds to the biblical Chorath Brook. Inspired by this sacred association, they chose to establish a monastery in this very spot. Over time, the cave came to be identified as the site where Joachim fervently prayed for the birth of Mary. Numerous churches and monastic structures were erected around Elijah’s cave, yet they fell into ruin by the end of the Byzantine era. During the Crusades, efforts to rebuild the monastery were undertaken in collaboration with Byzantine emperors. In the 13th century, Emperor Frederick II oversaw significant renovations, coinciding with his endeavors to reclaim Jerusalem from Muslim rule. During this period, the monastery became intertwined with burgeoning Marian traditions. Presently, it operates as an active monastery under the auspices of the nearby Gerasimus Monastery near Jericho.

This site holds profound significance for pilgrims en route to the Jordan River Baptismal site. With its flowing canal, verdant vegetation lining the deep gorge, a picturesque bridge spanning the canyon, and the imposing monastery edifice, it offers a compelling destination. Moreover, visitors can encounter relics of revered saints, adding to the spiritual allure of the location. From St. George’s Monastery, it’s a leisurely stroll of less than an hour to reach Jericho. You can choose to walk alongside the aqueduct or opt for the paths weaving through and above the water canal. Upon arrival in Jericho, finding accommodation in one of the city’s hostels is recommended.

The subsequent day offers an opportunity to explore the Christian sites of Jericho, including the nearby Quruntul Monastery and the Gerasimus Monastery nestled in the Jordan Valley. Additionally, pilgrims can visit the various monasteries and significant locations associated with the baptismal site along the Jordan River.