This is a rudimentary translation of articles from my book “Two that are One – the story of Omar Rais and the Shadeli Yashruti Zawiya in Acre”. While is far from ideal, it serves a purpose given the significance of the topic and the distinctiveness of the information contained. I have chosen to publish it in its current state, with the hope that a more refined translation will be available in the future.

Colors, Symbols and Numbers

Colors, symbols, and numbers are prevalent in sacred architecture and art globally, serving as gateways to comprehending the unseen realms. Given the departure from conventional reality, these elements offer powerful means of expression. Symbols, colors, geometry, and occasionally numbers provide avenues for conveying spiritual truths and accessing deeper dimensions of existence.

In the Zawiyas of Acre, numerous elements of sacred art and architecture abound, some of which may not be immediately visible but are deeply felt. These include various intricate diagrams (mandalas), intricate interplays of light and shadow, a rich array of colors, shapes, proportions, numbers, symbols, and sacred geometry. The overall arrangement is meticulously crafted, with each component intricately related to the others, culminating in a cohesive whole that leaves a profound impact on the visitor.

Color

The Qur’an contains numerous intriguing references to color. For instance: “And He subjected for you whatever He has created on earth of varying colors. Surely in this is a sign for those who are mindful.” (Surah 16: An Nahl, The Bees, verse 13). Another example is: “Do you not see that Allah sends down rain from the sky with which We bring forth fruits of different colors?” (Surah 35: Fatir, The vision of the angels, verse 27).

In Islam, light serves as a metaphor for God, as illustrated in the light verse. The division of light into colors is perceived as a manifestation of divine illumination and an expression of the structure of the unseen realms, reminiscent of Kabala teachings. Within Sufi Islam, there is a symbolic association between four colors and the four elements: red symbolizes fire, yellow represents air, green embodies earth, and blue signifies water. These colors, often accompanied by white, are prominently featured in the flags of Sufi orders like the Rifa’i, and are reflected in the ceilings and windows of porticoes surrounding the Mashhad, as well as in the two octagonal domes of the hall. Notably, the colored windows in the Takia predominantly feature blue and yellow hues. According to Rosen Ayalon, blue symbolizes eternity in Islam, while gold signifies knowledge, with the knower being none other than the known.

Color, neither matter nor energy but rather a manifestation of light, serves as a symbol representing hidden realities. Its interpretation can vary widely, extending beyond mere symbolism to embodying a tangible reality—a garment of energy, so to speak. Thus, color transcends its visual representation to encapsulate deeper meanings and truths, reflecting the multifaceted nature of existence itself.

Blue is often perceived as the bridge between worlds, given its presence in both water and sky. Remarkably, it is the only color that manifests across all four elements: earth, water, sky, and even within fire. Renowned for its calming effect, blue has the power to draw individuals inward, facilitating introspection and relaxation. In terms of color psychology, blue activates the parasympathetic nervous system, resulting in a decrease in heart rate and blood pressure. Consequently, it is an ideal hue for creating meditative environments and promoting serenity. Across various religions—including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baha’i Faith—blue holds mystical significance, embodying spirituality and transcendence. On a more practical level, blue is believed to offer protection against the malevolent forces of the evil eye.

The pairing of blue and yellow hues, prevalent throughout the Zawiya, evokes an unconscious association with the sun in the sky. This connection dates back to ancient civilizations like Egypt and Persia, where these colors were linked to divinity. For instance, the mask of the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun features gold stripes against a blue backdrop, symbolizing the deity Amun Ra. Amun, the concealed god, is represented by the color blue (sky), while Ra, the sun god, is associated with the color yellow. Similarly, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, revered as one of the most exquisite, ancient, and mystical Muslim edifices globally, is adorned in gold and blue—a representation preserved from its original construction to the present day.

From what I gather, the blue and yellow hues at a Zawiya symbolize the sun, and consequently the seven heavens that Prophet Muhammad traversed to meet with God. These seven heavens were historically associated with the seven celestial bodies visible to the naked eye: the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The sun, with its vital heat, was seen as the driving force behind this celestial arrangement, making its representation a symbol for the entire system. This notion aligns with the practices of Sufi orders in the Middle Ages, who engaged with astrology as evidence of a divine order in the universe.

It’s fascinating how we experience the world through a filter of seven colors (the rainbow’s spectrum) on one hand, and seven sounds (the musical scale’s tones) on the other. Our primary senses engage with reality through this septenary filter. Observing the sky, we note seven celestial bodies in motion, unlike the stationary stars. This prominence of the number seven has led to its sanctification across cultures. In Sufism, this reverence is reflected in the spiritual philosophy of many orders, which follow a progression path divided into seven stages.

In certain Sufi traditions originating from Central Asia around the 12th century, such as the Qurbani, color symbolism holds a significant place. Disciples were encouraged to inform their Sheikh if a specific color appeared in their dreams, as this was believed to reveal insights into their spiritual condition. For instance, blue is associated with security and honesty, while red represents intuitive knowledge and a connection to the spiritual realm. There are seven colors that correspond to distinct stages of spiritual development. According to some color systems: the journey commences with white, denoting purity, and concludes with black, symbolizing self-annihilation. Similarly, in the meditative practices of the Shadeli Yashruti order, as instructed by Omar, the emergence of certain colors in one’s thoughts is interpreted as an indicator of their spiritual standing.

The interplay of black, red, and white recurs throughout the Zawiya, notably in the mandala on the floor of the southeast room (the Divan of Sheikh al-Hadi Yashruti) and in the hues of the columns along the central avenue. These colors form a pivotal theme in Islamic Sacred architecture, echoing a verse from the Quran: “And in the mountains are streaks of varying shades of white, red, and raven black” (Surah 35: Fatir, Vision of the Angels, verse 27).

The interplay of black, red, and white carries profound spiritual symbolism: the transformation of purity (white) through the crucible of life’s passions and trials (red fire) leads to a state represented by black. This metaphorical journey reflects the process of human experience, where purity is challenged and often obscured by the complexities of life, emotions, and desires, resulting in a metaphorical layer of darkness. This concept finds a parallel in Islamic tradition with the story of the black stone in Mecca. According to a Muslim hadith, during a moment of reflection, Caliph Omar expressed a pragmatic view of the black stone, acknowledging it merely as a stone, valued only because of the Prophet Muhammad’s reverence for it. Ali Ibn Taleb, the Prophet’s cousin and spiritual heir, offered a deeper insight, suggesting the stone was not ordinary but a celestial diamond from God’s throne, turned black from absorbing humanity’s sins. the process of white becoming black is considered to be the Chemical process.

The spiritual journey embodies a transformative reversal known as the “alchemical process.” In this path, a disciple in the Sufi tradition is tasked with cleansing the heart’s tarnished (black) mirror, using the red fire of love to soften and purify, thereby restoring its original white clarity. This concept of spiritual alchemy has been elaborated by eminent Sufi scholars like al-Ghazali in the 11th century, particularly in his works discussing the alchemy of the heart. Thus, spiritual alchemy stands as a foundational “science” within Sufi practice.

This theme of purification and transformation is vividly illustrated in the pilgrimage to Mecca, where the black stone, once a celestial diamond, absorbs the sins of the pilgrims, rendering them pure once more, and therefor entitled to wear a white robe. The Sufi path, often metaphorically referred to as “the Kaaba of the heart,” requires the aspirant to subject their heart to the purifying fire of love. This process is likened to the transformation of the dark night of sin into the white dawn of redemption, catalyzed by the red sun of love.

Within the Sufi orders, the color green is imbued with multifaceted symbolism. Primarily, green is revered as the color of Islam, initially representing the lush gardens of paradise. Islam’s flag features green prominently, and it is said that the Prophet Muhammad favored green garments. Beyond these associations, green is linked to the legendary figure of al-Khidr (“the Green”), a timeless being who guides individuals on their spiritual journey. His presence is so life-affirming that it is believed green grass springs forth under his feet.

This narrative elevates green to a symbol of vitality and resurgence, illustrating how life springs from dormancy into vibrant action, much like the earth rejuvenating and turning green after the rains. Spiritually, green signifies rebirth and a transformation from a mundane existence to a transcendent quest. This shift from the ‘horizontal journey’ of earthly life to the ‘vertical’ ascent towards spiritual enlightenment is akin to being reborn. Consequently, green has become the traditional color for the headwear of Sufi Sheikhs, symbolizing their commitment to this path of renewal and spiritual awakening.

Symbols

The circle is a powerful symbol of unity, eternity, and the infinite nature of existence, without beginning or end. Its form, where every point is equidistant from the center, represents the accessibility and omnipresence of the divine. Omar, drawing inspiration from this shape, saw it as a reflection of the Quranic verse “To Allah belong the east and the west, so wherever you turn, there is the face of Allah. Indeed, Allah is all-encompassing, all-knowing” (Surah 2: Al-Baqarah, verse 115). This verse encapsulates the idea of divine ubiquity and inclusiveness, a concept also embraced by the whirling dervishes in their ritual dance, symbolizing the soul’s journey towards divine unity.

The circle thus embodies not just unity but the soul’s deep yearning to return to its origin. It echoes the spiritual narrative that we originate from God and to Him, we shall return. This cyclical journey of departure and return, of emanation from and reunification with the Divine, is encapsulated in the simplicity and completeness of the circle, offering a profound metaphor for the spiritual path and the interconnectedness of all creation.

In contrast, the square represents the tangible, material world in which we dwell and endeavor. On a more elevated plane, it symbolizes the four rivers of Paradise or the foundational figures of Islam: the first four caliphs and the four major schools of Sharia (Islamic law), each representing a form of division or organization within the unity. Whereas the circle embodies unity and infinity, the square brings to mind division and the structured nature of our physical and spiritual lives.

In the earthly realm, the square stands for the four classical elements (earth, air, water, and fire) and the four states of matter (hot, cold, dry, and wet), highlighting the diverse and foundational aspects of physical existence. On the spiritual or metaphysical level, the number four delineates four distinct stages or dimensions of the spiritual journey: Sharia (the law), which provides the ethical and legal framework; Tarika (the path), the practical and mystical journey; Maarifa (gnosis), the stage of spiritual knowledge and enlightenment; and Hakika (truth), the realization of ultimate reality. This layered interpretation underscores the square’s significance in representing the multifaceted journey through life, both in the material and spiritual realms, marking it as a symbol of the structured pathways toward divine understanding and truth.

The octagon emerges as a pivotal symbol within the sacred architectural fabric of the Zawiya, notably dominating the design of spaces like the Mashhad and the Takia hall, where the motif of eight is extensively incorporated. The number eight transcends the natural world, represented by the number seven, by symbolizing the miraculous and the eternal. This significance is deeply intertwined with the Prophet Muhammad’s nocturnal journey, during which he ascended through the seven heavens to meet God in a realm beyond, often referred to as the “eighth heaven.” Additionally, the imagery of God’s throne, borne aloft by eight angels, further cements the octagon’s spiritual and mystical importance in Zawiya’s sacred architecture, marking it as a symbol of the throne of God.

Other significant symbols include the pentagram and the hexagon, or the Star of David, which will be explored in further detail elsewhere.

Mandalas

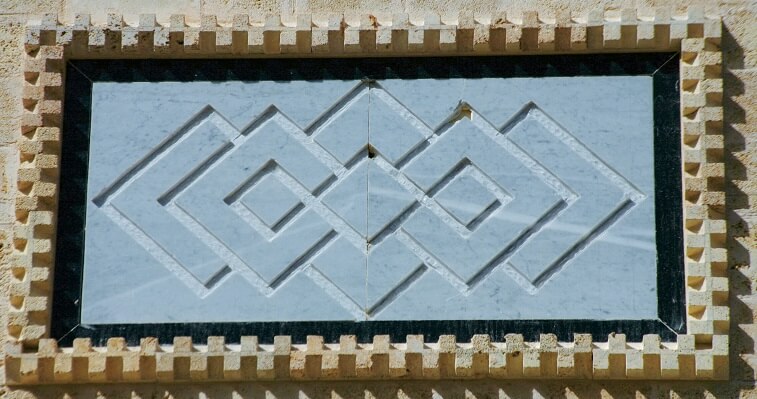

On the western façade of the Mashhad, along the central avenue, mandalas are displayed on the exterior wall, some featuring a square encased within a circle, which is itself enveloped by an octagon. Concealed within the square lies a central point (small circle), the heart of the mandala. As I interpret it, the octagon represents the spiritual path, the circle embodies the heavens, and the square signifies the earthly domain. This triad of geometric forms collectively evokes the architectural spirit of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, which symbolizes the Prophet Muhammad’s nocturnal voyage and the pivotal shift from the earthly to the spiritual realm—his spiritual ascension. Omar views this mandala as a manifestation of the “unity of being,” a core principle in Sufi Philosophy articulated by Ibn Arabi and further highlighted in the teachings of Ali Nur Al-Din Yashruti.

The mandala presents a deceptively simple yet deeply profound symbolism: the square, representing the material world, exists within and emanates from a greater unity and divine eternity, symbolized by the outer circle. Within this material realm, marked by the square, lies another circle (the point), this time internal, serving as a testament to the unity of being—the divine presence within the material world. This point, residing within humanity, completes the circle of creation. After the divinity (represented by the outer circle) manifests in the material (the square), it returns to itself through the unity witnessed by humanity. This internal point is also a symbol of consciousness. God’s declaration, “I was a hidden treasure and I wished to be known,” illustrates this concept: the outer circle represents the hidden treasure, brought into realization through the square, with the point within the square acting as the conduit for divine recognition in the world.

The octagon that encases this diagram holds its own layers of meaning. On one hand, it symbolizes the Prophet Muhammad’s nocturnal journey, an ascent through the seven heavens to a meeting with God in what might be termed “the eighth heaven” – a realm beyond physical spaces where he was bestowed with the secrets of prayer. This journey highlights the octagon as a symbol of spiritual ascension and divine encounter. On the other hand, the octagon is also depicted as God’s throne, upheld by eight angels, a representation that manifests in the attributes of the ideal, complete human being. Furthermore, the octagon embodies the concept of eternity and is closely associated with the infinity symbol, reinforcing its significance in expressing the endless, cyclical nature of the divine and the universe.

Within the precincts of the Zawiya, the octagon motif recurs, notably on the floors of the Crusader Halls, the erstwhile kitchen zone, and within the divan of Sheikh Al Hadi Yashruti. This geometric form also defines the architecture of the tomb structures in Mashhad and frames the twin colored glass domes.

On the other hand the big Dome of the Takia hall is supported by eight arches and has eight windows. The number eight, in these context, serves as a foundation carrying the circle above it, reminiscent of the Dome of the Rock’s structural symbolism. This arrangement might suggest that the circle represents the eternal and infinite aspect of divinity, while the octagon embodies the divine light emanating from this eternal source. The interplay between these two divine manifestations, bound by the cords of love, intimates a cosmic unity. It’s through this divine interconnection that creation itself is believed to have been brought into being and continues to exist.

The mandala in the Diwan of Sheikh Al Hadi Yashruti

Among the plethora of diagrams (mandalas) and symbols scattered throughout the Zawiya, the most intricate and captivating is found on the floor of the Diwan room of Sheikh Al Hadi Yashruti. Omar points out that it was Sheikh Ahmed Yashruti who prescribed the design of this diagram, drawing inspiration from pre-existing patterns. This particular mandala is situated within a spacious square room, sprawling across the majority of the floor area,

The diagram features an exquisite marble mosaic at its core, with a blue sun circle framed by a slender black circular band, from which yellow rays extend across a white circular backdrop. This motif represents the concept of a “spiritual sun”: while the physical sun is depicted as a yellow circle set against a blue sky, mystical teachings propose the existence of a spiritual light beyond the physical. Thus, behind the physical sun lies a spiritual counterpart. This idea is often represented—not exclusively in Islam—by a blue (or black) circle against a yellow (or white) background, suggesting that the principles governing the spiritual realm are frequently inverse to those of the physical world. For instance, in the material world, giving more results in having less, whereas in the spiritual domain, the act of giving amplifies abundance.

The “spiritual sun” symbolizes the “Hadrah Muhammadiya”, the divine throne that Prophet Muhammad ascended to during his nocturnal journey. Encircling this spiritual sun, at the tips of the yellow rays, lies a larger circle containing sixteen smaller circles, reminiscent of eyes. These circles feature a red outer ring with a smaller white circle inside, which in turn encloses an even smaller blue circle, all converging towards the center. This creates an eye-like structure with three distinct layers, akin to the human eye. The small blue circles within the white and red seem drawn towards the central large blue circle, reflecting a principle of similarity attracting similarity. In Sufi terms, this is akin to a droplet yearning to merge back into the ocean. The pull of the small blue circles towards the central blue circle, existing autonomously at the heart of the design, metaphorically represents the human soul’s longing to return to its origin, the Creator.

The sixteen eyes form a large circle set against a backdrop of white circular marble, encircling the central blue sun. These eyes align with the ends of sixteen golden rays radiating from the blue sun, all of which are bordered by a dark black strip that defines the outer edge of the white area but is itself encircled by a slim strip of white. Nested within this configuration is a square, delineated by a white square bar, where the circle and the square meet at their edges, forming four corners filled with black marble. Extending outward in the four cardinal directions from the square are four rhombuses, each bisected into red and black halves. Surrounding the entire composition is another, larger square, outlined by a black line and adorned with black and red marble triangles at its corners.

The colors black, red, and white featured in the diagram represent the alchemical transformation one undergoes on the spiritual path, a process of purifying the heart and unveiling the divine presence within. The external squares, showcasing these colors, are thought to symbolize the earthly aspects of this journey, along with the external knowledge required to navigate it. In contrast, the blue color, present in the center and the “eyes,” is believed to signify the spiritual segment of the journey, reflecting the inner wisdom and understanding of the path.

Similar to concepts in Kabbalah, the circle represents a form of higher governance associated with the spiritual state of humanity, where unity prevails, known as “the governance of the circle.” Conversely, the square is linked to the earthly realm of duality, corresponding to the “governance of the tree of knowledge – right and wrong.” The colors red, black, and white are tied to the developmental processes occurring within this dualistic domain, whereas the colors yellow and blue relate to the principles governing the spiritual realms.

The sixteen “eyes” depicted in the mosaic may be interpreted as members of the brotherhood, each harboring a divine spark eager to merge with the great blue circle (the Sheikh) at the center. This central blue sun represents God’s presence in the world, while the blue circles within the sixteen eyes symbolize the divine presence within each individual. Omar often remarked that “from any part of the circle you can reach the center,” emphasizing the accessibility of the divine. However, upon reaching this central point, a transformative shift in perspective is required—from the material to the spiritual realm—revealing the underlying unity of all things.

The plan of the Zawiya courtyards

To wrap up our exploration of the Zawiya, it’s fitting to touch upon the courtyards within the compound. Spanning over 2,000 square meters, this expansive area is segmented into various parts, nestled among the different buildings to form a series of plazas and walkways. As of 2021, these courtyards have seen no significant activity beyond paving, though there are plans for a garden that have yet to be realized. I’ve decided to present this plan as I understand it, aiming to shed light on the intent and thought process behind the planning, even if it might not come to fruition.

The trio of courtyard sections and their intended gardens serve as metaphors for three phases of human life and spiritual evolution: the entrance’s fountain and courtyard epitomize birth, embodying the genesis of existence and spiritual awakening. The boulevard, characterized by its flowing water, mirrors the journey undertaken throughout one’s life, encapsulating the myriad experiences and growth encountered along the way. Finally, the courtyard’s secluded pool and “Hidden Garden” represent the conclusion of life and the ensuing opportunity for the soul’s return and reunion with the Divine.

The entrance fountain is a manifestation of vitality, embodying the act of creation and marking the commencement of the human journey. It signifies both the physical inception of life and a spiritual awakening, bridging dimensions. In Sacred Muslim architecture, a fountain often symbolizes the passage between realms, making the Zawiya’s entrance fountain particularly significant. It is designed to stand prominently above ground level, with water joyously springing forth, symbolizing an outburst of life and enlightenment. Adjacent to this fountain, verses from the first revelation of the Quran to Prophet Muhammad will be inscribed, beginning with: “Read, O Prophet, in the Name of your Lord Who created, created humans from a clinging clot. Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous, who taught by the pen, taught humanity what they knew not.” (Surah 96: Al-‘Alaq, verses 1-5).

The central boulevard, flanked by the Mashhad’s columned portico, symbolizes life’s journey, commencing at one point and culminating at another. This pathway is mirrored in the Prophet Muhammad’s nocturnal journey – “Al Isra al Mi’raj.” Inscriptions at both the start and finish of this route will feature verses describing this sacred journey, commencing with: “Glory be to the One Who took His servant Muhammad by night from the Sacred Mosque to the Farthest Mosque whose surroundings We have blessed, so that We may show him some of Our signs. Indeed, He alone is the All-Hearing, All-Seeing.” (Surah 17: Al Isra, The Night Journey, verse 1). The boulevard is conceived to be broad and shaded, fostering communal gatherings and the vibrant flow of life within its bounds (this flow is punctuated by pauses at four small square water pools).

Located in the northern part, away from the gaze of those entering the Zawiya and nestled between the Mashhad and the chambers adjacent to the moat, lies a grand shallow pool. This pool, set beneath the ground level and encircled by trees and benches, forms the Hidden Garden. This secluded space is evoked in the Surah of the Star: “And he certainly saw that angel descend a second time, at the Lote Tree of the most extreme limit in the seventh heaven, near which is the Garden of Eternal Residence, while the Lote Tree was overwhelmed with heavenly splendors!” (Surah 53: An-Najm, The Star, verses 13-16).

The garden is designed to be the sole area within the Zawiya courtyards where vegetation reminiscent of the Garden of Eden, such as the olive tree, will be planted. This space is dedicated to contemplation and introspection. The pool, conceived as a reflective surface mirroring the journey of human life, embodies the concept of death as not only the cessation of life but also as a gateway to a new beginning. Additionally, it symbolizes a repository for all the positive deeds and impacts a person has accumulated throughout their life.

Near the pool, the opening Surah of the Quran, Al Fatiha, will be engraved. This Surah is recited in Muslim funerals and is a central part of daily prayers: “In the name of God, the Merciful and Merciful. Glory to God, Lord of the worlds, Merciful and Merciful on the Day of Judgment. We will worship you and hope for your salvation. Rest in peace Straightens, the rest of those to whom grace has been inclined, not of those on whom the heat has been poured out, nor of those who go astray.”

From my perspective, the design of the gardens reflects a profound understanding and is ingeniously planned, fostering anticipation for its eventual realization.