This is a rudimentary translation of articles from my book “Goddess Culture in Israel“. While it is far from ideal, it serves a purpose given the significance of the topic and the distinctiveness of the information contained. I have chosen to publish it in its current state, with the hope that a more refined translation will be available in the future.

Goddess worship

Archaeologists report that in the Goddesses’ era, religious practices were common across three tiers. At the family level, households engaged in private rituals using miniatures, statues, and incense, incorporating them into daily routines like food preservation, cooking, artisanal work, childcare, and strengthening familial relationships. On a larger scale, communities and villages organized public rituals, particularly during key farming seasons, linking these ceremonies to agricultural activities, joint tool making, and collective tasks such as plowing and reaping, with many of these traditions surviving in rural folklore. Communal rituals also included ceremonies for initiations and strengthening community ties, marking important life events like weddings, births, and other milestones. At the top tier, significant religious activities took place at regional centers and natural sacred sites, where pilgrimages and gatherings occurred on certain days annually to celebrate celestial events like solstices.

Group worship aligned with the cycle of agricultural labor, integrating aspects like dance, music, and folklore, notably through mask usage. Community ceremonies also celebrated key personal milestones, including birth, death, and transitional moments such as coming of age and wedlock. Furthermore, shamans conducted essential initiatory religious ceremonies. These rites frequently induced ecstatic states and centered on healing, leading participants through deep spiritual journeys and transformations.

Regional worship was deeply connected to astronomical occurrences, such as the full moon, and took place at specific annual times that corresponded with the sun’s path, including the solstice for the longest day, the solstice for the shortest day, and the equinoxes. The solstices, marking the year’s longest and shortest days, were especially important in the Middle East regions, as they signaled shifts from intense labor periods to times of relaxation. The shortest day was celebrated after finishing plowing, sowing, and preparing the land for the rainy season, indicating the beginning of heavy rains and a period of rest during the winter months. Conversely, the longest day was observed after the harvest and gathering season concluded, marking the start of the hot, prolonged summer days. During these periods, individuals were drawn to leave their communities temporarily, breaking away from daily routines to gather with others and connect with the Goddess. These assemblies offered a chance to find oneself and engage with the divine, promoting a sense of spiritual refreshment and renewal.

The regional gathering sites were unique natural locations. With the Goddess’s blessing to farm the land, humans felt authorized to amplify its energies. Consequently, they built sacred spaces, such as earthen mounds, wooden posts, and megalithic structures like dolmens, menhirs, and stone circles. This collective endeavor was carried out with enthusiasm and a sense of common goal, rather than obligation. It was a creative and artistic act, turning the landscape into sacred mandalas that represented harmony between humans and nature, and also among people themselves.

The sacred enclosures acted as cosmic symbols, their entrances oriented towards celestial bodies and important terrestrial features such as mountains. Archaeologist Ofer Bar Yosef notes that ceremonies conducted within these hallowed grounds, especially during critical agricultural periods like the harvest or planting seasons, were characterized by magnificence. Preparations for these events extended over several months, with attendees creating ceremonial items such as figurines, masks, and vibrant garments. Frequently, these observances involved pilgrimages to the sacred sites, underscoring their significance in the community’s spiritual and cultural life [1].

At these regional assemblies, individuals from different communities came together for days or weeks. In this time, people would move among various village encampments, participating in the trade of goods and sharing knowledge. These gatherings served not just for the exchange of commodities but also as a platform for social interaction and the forging of new relationships with both men and women. It’s plausible that in the evenings, there were ceremonies filled with sacred music and song. Specifically, individuals might have played instruments made from materials like bone or bamboo, such as flutes and drums, alongside vocal accompaniment. This mix of sounds likely created vibrations capable of changing and enhancing the energy of both the participants and their environment, similar to rituals performed in the deep recesses of caves by our hunter-gatherer ancestors.

Music, dance, and singing were central to the ceremonies and rituals of the era. In addition to well-known instruments such as flutes and drums, it’s probable that shells were utilized to create sounds, and stones with particular acoustic features were used as percussion tools. Archaeologist Ofer Bar Yosef has noted that dance was fundamental in religious ceremonies, at times continuing all night and leading to trance states, similar to practices in modern “primitive” societies. Sound played a critical role in ancient times. Research has shown that people in the cave era chose sacred sites partly for their acoustic qualities [2]. Researcher Paul Devereux has shown that megalithic sites like Stonehenge have stones with specific acoustic properties. Clearly, music and dance, together with art and religion, form essential aspects of human culture, intertwined in their expression and importance.

Humans worked together to create these sacred spaces and structures, joining efforts to stack stones or mound earth to craft patterns or embankments at these locations. Following their construction, rituals were performed within these areas to express gratitude to the Goddess and to solicit her blessings. In these sacred sites, people forged connections with celestial entities, drawing upon their energy to channel it to earth for the communal good of everyone involved.

Sexuality, Fertility and the Goddess

In the Goddess-centric culture, sexuality was deeply significant, intertwined with the fertility and life-generating aspects of Mother Earth. It was conceived that Mother Earth, resembling a womb, was fertilized by the sky, embodying the generative force of the male heavens. Mircea Eliade comments on this, noting: “The holiness of sexual life, especially female sexuality, is entwined with the wondrous mystery of creation. Virgin births, the ‘Hieros Gamos’ (Sacred Marriage), and ritualistic orgies serve as manifestations of the spiritual essence of sexuality across different settings”. Eliade draws attention to the intricate symbolism, largely anthropomorphic, linking femininity and sexuality with the phases of the moon, the earth as a nurturing womb, and the mysterious cycle of plant life.

In the Goddess culture’s perspective, sexual acts carried out in a magically resonant manner were thought to lead to better harvests. Thus, these rituals frequently took place in the fields, viewed as acts that prompted cosmic rejuvenation and widespread germination. Echoes of this belief persist in the name of the Canaanite deity of rain and agriculture, “Baal,” which translates to “the cohabiter.” Rain was seen as the sky uniting with the earth, similar to a conjugal act, and rituals linked to Baal, like the sacred marriage, were thought to facilitate this celestial and terrestrial union, resulting in copious rainfall.

Eliade points out the religious importance of the interaction between sexes, relating it to the concept of completeness and unity. He explains: “The idea of completion, bridging the sexual and cosmological realms, carries religious meanings that go beyond simple ‘male’ or ‘female’ labels. This concept is intended to structure the world and clarify the enigma of its creation and mysterious renewal.”

The relationship between the sexes, leading to procreation, was viewed as a gift from Mother Earth. Eliade suggests that the Earth is a hierophany—a manifestation of the divine linked to procreation: “The earth is the origin of all life forms; it represents a perpetual cycle of creation. Whether the religious experience inspired by Earth’s disclosure is perceived as a ‘sacred presence,’ a specific deity, or a tradition arising from dim recollections, the core concept of motherhood and the unceasing force of creation is a constant.”

In the Goddess era, pregnancy was enveloped in sacredness, necessitating spiritual and physical preparations. Birth was considered a divine event, often taking place in special birth temples. In Çatalhöyük, Turkey, archaeologists have found such temples, identifiable by rooms with walls and floors painted red. These spaces feature paintings of women in various childbirth positions, highlighting the sanctity of the area. A low sofa in these rooms likely functioned as the birthing bed. Similarly, at Lepenski Vir, small huts with red-painted floors have been unearthed, with stone arrangements mimicking the cervix and womb, suggesting their use for childbirth rituals. While similar structures have yet to be found in Israel, it’s theorized that huts near Ohalo by the Sea of Galilee and the small circular buildings in Hayonim Cave might have served comparable roles.

Death and Rebirth

With the rise of Goddess culture, there was a notable change in burial customs, mirroring evolving attitudes towards the afterlife. People were buried in the fetal position, a practice Marija Gimbutas identified as Old Europe’s most significant burial symbol. This position was symbolic of life’s cyclicality, representing the renewal and continuation of life from death, akin to the birth-life-death-rebirth spiral. This concept was physically represented through graves designed to resemble a womb, signifying rebirth and often shaped in the likeness of the Goddess. This symbolism is also evident in tombs linked to the Goddess culture found in Israel, reflecting a consistent thematic connection across these ancient societies.

Eliade interprets the burial of individuals in a fetal position as symbolizing a belief in reincarnation, where the burial acts metaphorically reverse the processes of birth and gestation under the auspices of the Goddess. The appearance of the deceased in dreams was seen as proof of the soul’s persistence and the reality of an afterlife. The items placed with the deceased suggest a belief in their continued existence and activity, whether in another realm or in relation to the living world. From this perspective, the grave site becomes a ceremonial area resembling a home for the deceased, emblematic of a womb. The burial ceremony itself included rituals of opening and closing this symbolic domicile, mirroring the act of birth and signifying a passage to the afterlife.

The masked skulls, often found buried in groups, might have functioned as focal points for reverence. Approximately a year after interment, they were exhumed, followed by a purification process, likely involving rituals designed to assist the spirit’s journey to the afterlife. The facial reconstruction using clay was thought to employ sympathetic magic, aiding the deceased’s rebirth into the next world and facilitating dialogue with ancestral spirits. These skulls, retrieved from their graves for ceremonial use, were periodically exposed to the moon, sun, and stars, possibly to charge them with energy. This practice finds reflections in later Celtic traditions, suggesting a continuity of belief in the power of celestial bodies to sanctify or empower sacred objects.

The adorned skulls were placed in particular spots, frequently near or inside homes, like under floorboards, merging the spaces of the dead and the living. As Eliade observes, the head is regarded as the soul’s abode, being the site through which people experience dreams and states of ecstasy, recognizing a spiritual identity distinct from the bodily one. In the imagery of the cosmic tree, the head symbolizes a seed with the potential to germinate in the afterlife. Consequently, the skull was seen as the origin of spiritual renewal, a vessel of arcane energy.

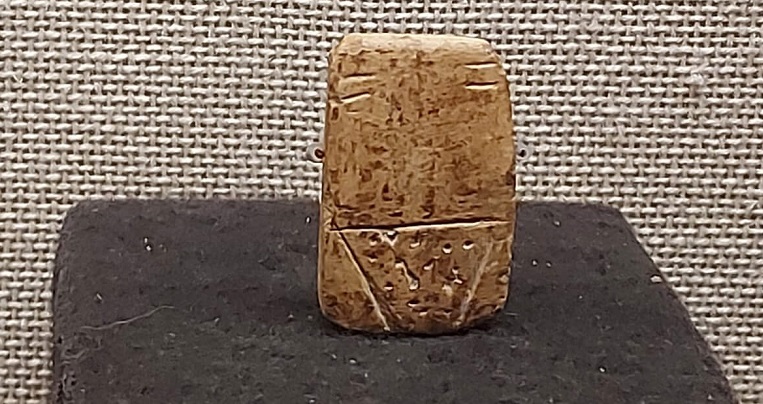

The craftsmanship of the masks and the embellished skulls sheds light on the principles and convictions of the Goddess culture. Notably, the eyes on the plastered skulls were originally made using oysters obtained from distant locations. Over time, these materials evolved to include shells or grains of wheat, reflecting changes in religious or cultural beliefs. The depiction of the eyes varied, being either open and hollow or closed, with each style conveying distinct implications. In the early phases of the Goddess culture, such as in Jericho, the eyes were fashioned in an oval shape. As the community grew, moving into valleys and forming larger settlements like Ain Ghazal, the eye designs shifted to a circular form. Lewis Williams interprets this progression as indicative of the shamanic voyages prevalent at the time, with shamans undergoing experiences of death and rebirth during rituals that bridged different realms. The trance state, resulting in the physical opening of the eyes and enlargement of the pupils. This evolution hints at the Goddess culture’s intricate comprehension of the afterlife.

In the burials of women from the era of the Goddess culture, a variety of artifacts linked to sacred crafts were frequently found. These included implements for grinding grains, baking, weaving, dyeing fabrics, crafting pottery, and decorating jars. Moreover, skeletons or parts of animals, which mirrored the diverse representations of the Goddess, were often included in these burial sites. Jewelry and figurines depicting the Goddess were also common among the items interred with the deceased. Marija Gimbutas observed that in the Balkans, the graves of young women were not just filled with figurines but also with models of temples, leading her to suggest that these were the final resting places of priestesses. This evidence points to the profound spiritual and societal roles that women held, as well as the rich symbolic world they inhabited, where crafts, animals, and sacred symbols played integral parts in their connection to the divine.

In the Chalcolithic period, the last phase of the Goddess culture witnessed significant changes in burial customs. The introduction of secondary burial practices, involving the reinterment of bones in small containers called ossuaries, became common. These ossuaries often bore designs that blended images of houses with the human figure, frequently depicting female forms. They were placed in burial caves or within circular burial structures, such as those discovered in Palmachim, and each location accommodated the remains of multiple individuals. The use of dolmens and tumuli — specific grave fields — for burials grew widespread. The dead were moved from their homes to these final resting spots, some of which were situated underground, exemplified by the burial cave in Peki’in. This evolution in burial practices reflects broader shifts in societal and religious attitudes during this era, emphasizing the community’s ongoing reverence for the deceased and the sacred through these complex funerary traditions.

The shift in burial customs during the final stages of the Goddess culture, particularly in the Chalcolithic period, might appear as a departure from previous practices, but it actually signifies a continuation of the underlying cultural and religious principles. Ofer Ben Yosef has posited that the design of the ossuaries, which merged images of houses with human forms, was symbolically akin to wheat silos. This analogy underscores a belief in regeneration and rebirth: just as seeds buried in the earth eventually germinate and grow, so too are the deceased envisioned to experience resurrection. This viewpoint underscores a lasting adherence to the worship of the ancient agricultural mother goddess, drawing a parallel between the process of seed germination and the notion of life after death. The evolution of funerary practices thus reflects not a change in fundamental beliefs but a varied expression of the same veneration for life’s cyclical nature and the perpetual renewal it entails, deeply rooted in the agricultural cycles revered by the Goddess culture.

The transformation in burial customs during the Chalcolithic Period, a key era of the Goddess culture, mirrors changes seen globally, including in regions like the Balkans and Malta. In these areas, a notable shift toward constructing subterranean spaces began, leading to sophisticated cave systems that served dual functions as tombs and sacred spaces, such as the Hypogeum in Malta. Similarly, in Europe, the widespread establishment of tumulus and dolmen burial fields occurred, evolving in some regions into the creation of long mounds. These mounds, sometimes extending up to a hundred meters, contained underground passages and chambers culminating in an inner sanctum, metaphorically resembling a birth canal and womb, known as Long Barrows. Avebury, England, is home to a prominent example of such a structure. These mounds, significant to burial fields and extensive sacred complexes, signify a purposeful distinction between the realms of the living and the dead, moving the domain of the deceased to consecrated grounds and the underworld.

Written language and Symbols

The fertility dimension of the Goddess went beyond the tangible to include both abstract and mental aspects. A crucial question in this regard is whether the Goddess culture had its own writing system. Marija Gimbutas argues in “Language of the Goddess” that such a system of writing indeed existed. She proposes that the symbols discovered in Old Europe serve as the grammar and syntax of a kind of meta-language, enabling the conveyance of a broad spectrum of meanings. Gimbutas points out that this language appears on urns (vases) and is made up of geometric symbols that have yet to be deciphered, possibly connecting it to other ancient languages from early Crete and Cyprus that also remain uninterpreted. The language of the Goddess highlights the sacred bonds between human society and the environment, along with personal relationships, with a particular emphasis on women and the elements of divine femininity in the sphere of religion and cultural life..

The Goddess culture deeply resonated with the functions of the brain’s right hemisphere, known for processing thoughts through images and symbols, in contrast to the left hemisphere’s analytical nature, which prioritizes details, numbers, and concrete data. The mindset within the Goddess culture was richly mythical, narrative, and symbolic, integrating various layers of meaning into a unified framework of comprehension. This characteristic is clearly seen in the wide array of Goddess figurines’ representations. Marija Gimbutas highlighted the abstract conveyance of the Goddess’s language through symbols, evident in geometric patterns—like lines, chevrons, waves, meanders, dots, and more—adorned on vases, jewelry, figurines, and additional artifacts from that period.

A notable characteristic of the art from this period is the appearance of geometric patterns on pebbles and stone slabs, the meaning of which is still not fully understood. The art, especially on items used by people, frequently showcases schematic and geometric designs. In human representations, there’s an abstract approach, with stripes used for eyes, circles for mouths, and so on. These artistic features indicate the existence of a symbolic language, reminiscent of an early version of emojis [3].

Globally, discoveries indicate the existence of ancient languages still awaiting decipherment, with some tracing back to the Goddess era. In Gradeshnitsa, Bulgaria, tablets inscribed with an undeciphered script from 6,000 years ago were unearthed, linked to the sophisticated Goddess culture identified as the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture. Similarly, in Israel, Yehuda Rothblum suggests that the rock art in the Negev depicts a form of symbolic language, with the oldest examples dating back 8,000 years [4].

The Moon – a sympathetic network of Magic

The moon held profound significance for early humans, viewed as the celestial body that regulated cyclical changes and served as a measure of time. Wave-like carvings on cave walls, bones, and stones found in various caves are interpreted by Alexander Marshack as depictions of lunar phases and their influence. Marshack asserts, “A symbolic system for keeping time, based on the moon’s phases, was established by the late Paleolithic era.” This lunar-centric framework was foundational for seasonal rituals and the development of writing. He regards these wavy patterns as a primitive form of script that recorded sequences and expressed intentions, calling it “an individual act of participation.” Mircea Eliade supports this view, proposing that the acknowledgment of the lunar cycle as a timekeeping method dates back at least 25,000 years.

The cycles of the moon played a crucial role in timekeeping, thus orchestrating the rhythms of existence. This celestial body’s impact enabled adaptations and connections, establishing a uniform framework amidst what could appear as an infinite realm governed by separate forces. The moon stood out as a cohesive force, weaving its influence across the earth, symbolized by motifs such as shells, waves, and spirals. It was perceived as a linking element among different spheres and elements, like water, earth, sky, and the dynamics of light and shadow.

Eliade suggests that the moon plays a pivotal role in orchestrating a vast interplay of destinies and states of being, incorporating harmonies, symmetries, and reciprocal interactions, all tuned to the rhythms of lunar cycles. This forms an expansive “web” that intricately connects humans, rainfall, vegetation, animals, death, and the afterlife. The moon presides over all facets of life and acts as a guide for the souls of the departed. Its symbolism, deeply entrenched in ancient times, includes water, femininity, vegetation, fertility, cyclicality, birth, death, and rebirth.

Ancient civilizations attributed rain, tidal movements, and enhanced plant growth to the influence of the moon, particularly during its full phase, prompting certain cultures to refrain from harvesting at this time. Lunar symbols were linked with intuition, regarded as a natural endowment from the moon, which early humans found more instinctive than analytical reasoning. The profound comprehension of the cosmos held by ancient peoples remains challenging for modern individuals to grasp entirely. For early humans, participating in rituals during the full and waning moons positioned them at the focal point of the universe’s sympathetic energies, fostering vitality and forging connections with dimensions transcending time and space.

The ancients observed that during its waning phase, the moon appears in the early part of the night, resembling a semicircle or the letter C in the sky. Conversely, when the moon is waxing, it emerges later in the night, forming an inverted semicircle. These phases of waning and waxing, along with the transitions to the new and full moon, brought to mind images of cattle horns for the ancients, leading to the association of “horns” symbolism with the moon. Thus, the horned God, representing mastery over the cycles of time and nature, became linked to the moon. This dual appearance of the moon within a single cycle symbolized the harmony of opposites.

The moon completes its orbit around Earth every 27.3 days, coinciding with its rotation on its axis. This duration closely mirrors the average menstrual cycle, hinting at a connection between women and the lunar cycle. However, due to Earth’s solar orbit, the moon’s solar alignment shifts, lengthening the lunar month to 29.5 days. In response, cultures influenced by the moon’s mystical properties divided the year based on the lunar cycle, not by its visible phases but by its intrinsic cycle, resulting in a year of 13 months, each lasting 28 days. This calendar subtly synchronized with the moon’s rotation rather than its observable appearance from Earth. Conversely, cultures that harmonized the moon’s cycle with the sun adopted a 12-month year, with each month approximately 29.5 days long, similar to the Hebrew calendar. To reconcile the lunar and solar cycles, an additional month was often inserted biennially or triennially.

Eliade describes in ancient cultures’ mysticism that salvation was perceived to occur when an individual achieved inner harmony between the two celestial cycles, blending the energy of the sun with that of the moon. This required understanding the moon’s profound essence as the regulator of life’s cycles. The “unification” of these two sacred cosmic energies—the moon and the sun—was aimed at facilitating their reintegration into divine unity.

Eliade explores the mysticism surrounding the moon in “Patterns in Comparative Religion,” culminating in a profound observation: the moon, he suggests, acts as a mirror reflecting the true nature of human existence. In this reflection, individuals see themselves and their lives mirrored in the lunar cycle. This is why the moon’s symbolism and mythology resonate deeply, offering lessons that are both poignant and enlightening. The moon governs over death and fertility, embodies both drama and the process of initiation. Its essence is change and cycles, yet it also represents the cyclical nature of return—a dual fate that both wounds and heals. Life’s manifestations may be fleeting, dissolving in moments, yet through the moon’s principle of ‘eternal return,’ they find renewal.

The question of whether the cavemen possessed a developed spirituality, including a mysticism centered around the moon and stars, and systems of symbols related to the measurement of time, remains a significant area of inquiry. While it’s clear that early humans engaged in practical activities for survival, such as hunting mammoths and gathering around fires, evidence suggests that they also had a deep sense of the sacred. Archaeological findings, such as cave paintings and burial sites, indicate that early humans paid homage to natural elements and celestial bodies, possibly viewing them as manifestations of divinity or as integral parts of their spiritual and ritualistic lives. The reverence for the moon (and the sun or other natural phenomena) could have stemmed from its influence on natural cycles, which were crucial for their survival. This suggests that early humans were not solely focused on immediate physical needs but also engaged in the contemplation of greater existential and cosmological questions, integrating them into their cultural and spiritual practices..

For hundreds of thousands of years, humans lived in caves and traversed the earth, relying on hunting and gathering for sustenance. However, there came a significant shift when they began cultivating plants, establishing settlements, and transitioning their religious devotion from the Lord of the Animals to the worship of the Great Goddess—Mother Earth.

The role of Men

The role of men in a matriarchal society sparks inquiry [5], with the prevailing notion suggesting that men were primarily responsible for impregnating females and supporting growth. However, they were not credited with the power to grant life or govern the cycles of life and death, duties reserved for women. This differentiation underscored the significance of women within these societies. Despite the relationship between men and women, the fulfillment of their respective roles was viewed as the harmonious fusion of opposites.

The phallus symbolizes life energy, while the vagina represents the origin and nurturing of life. In ancient belief systems, the God served as the counterpart to the Goddess, participating in the Sacred marriage ceremony to ensure the fertility of the earth. However, the land itself, symbolizing the realm, was considered feminine. Despite relying on male contribution and support, it possessed inherent vitality and agency. One could compare the man to the sky, embodying the driving force of the sun’s energy that promotes growth and the raindrops that initiate sprouting. In contrast, the woman symbolizes the hearth, the earth, and the life emerging from dormancy into action.

To facilitate the creation of life, a woman depends on the fertilization or stimulation offered by a man. In Goddess cultures, the sacred union between men and women was a regular occurrence, especially during annual rituals such as the summer solstice. Employing a system of symbols and signs that mirrored cosmology and the enigmas of creation, the woman would summon her selected partner. Once the man fulfilled his role in impregnating the woman, he could be metaphorically “disposed of”. This concept is exemplified in depictions of gods like the Egyptian Osiris, who undergoes death following the sexual act and subsequently becomes a ruler of the underworld.

If the man persists beyond the act of fertilization, he assumes the role of the spouse to the ancient earth Goddess. This is evident in depictions of male vegetation gods like the Canaanite Adonis, who traverses cycles of growth and celibacy, serving as companion to the pregnant vegetation Goddess. The male deity of vegetation takes on various forms that mirror the changing seasons: in spring, he manifests as a youthful figure who rouses the ancient earth Goddess from dormancy; in summer, he becomes an adult overseeing the harvest, symbolized by the sickle; and in autumn and winter, he transforms into an elderly figure symbolizing wisdom, life after death, and the potential for existence in other realms.

In essence, men were integral to the Goddess culture, which was not solely centered around women, just as our patriarchal culture isn’t exclusively for men. The Goddess culture embraced feminine spirituality that both genders participated in and believed in. It appears that this culture fostered peace and harmony between the Sexes, within society and the world at large.

[1] Bar-Yosef, Ofer, Garfinkel, Yosef The Prehistory of the Land of Israel: Human Culture Before the Invention of Writing, Ariel 2008. p. 135.

[2] Fazenda, Bruno, et al. “Cave acoustics in prehistory: Exploring the association of Palaeolithic visual motifs and acoustic response.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 142.3 (2017): 1332-1349.

[3] Lewis Williams, on the other hand, interprets the geometric shapes as an expression of the first stage in the shamanic experience

[4] Rothblit, Yehuda. (2012). Interpreting Heaven – deciphering rock paintings in Israel. Karchum, Mitzpe Ramon.

[5] In principle, matriarchal societies typify ancient societies rooted in small-scale agriculture, while patriarchal societies are emblematic of nomadic societies. This distinction is mirrored in the divine figures of different societies, reflecting their religious and social frameworks.

[1] An independent researcher from Harvard, author of the book “Roots of Culture,” posits a theory suggesting that engravings found on bones and stones served as a symbolic language, a calendar, and a lunar time diary. Marshack, A. (1972). The roots of civilization: The cognitive beginnings of man’s first art, symbol and notation. London, UK: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.