This is a rudimentary translation of articles from my book “Goddess Culture in Israel“. While it is far from ideal, it serves a purpose given the significance of the topic and the distinctiveness of the information contained. I have chosen to publish it in its current state, with the hope that a more refined translation will be available in the future.

Full appearance of the Goddess Culture

Between the 7th and 5th millennia BC, the Goddess culture attained its zenith in both presence and advancement, coinciding with the advent of pottery making. Consequently, this era, spanning over two thousand years, is referred to as the Ceramic Period (6,400-4,500 BC). In this period, sizable and tranquil villages emerged, art and aesthetics flourished, and a culture of trade, cooperation, and the fostering of crafts expanded across vast regions.

Pottery is among the inventions that significantly altered human development, emerging 2500 years after agriculture began. It’s as though Mother Earth recognized that humans had adeptly learned to utilize fire and stone, plaster and lime, and thus decided to bestow upon them the next milestone in development: pottery. She inspired the women priests with the notion that clay could be transformed at high temperatures, altering its structure. To produce ceramics from clay, a temperature of around 1,000 degrees is necessary, while creating advanced ceramics requires temperatures exceeding 1,200 degrees (the lower the temperature, the more reddish the vessel, akin to the terracotta style).

To achieve this, they initially excavated pits for the kiln and subsequently constructed kilns above ground. For the materials to undergo transformation, the vessels needed to be fired in a kiln for an extended period using ample combustible materials. Afterwards, the kiln was to be allowed to cool gradually and slowly, followed by a final firing after the vessels had been painted. This process demanded organization, resources, and time, making it impractical to invest such effort for a single item, unless it involved mass production for the entire village or tribe. Priestesses were often entrusted with this task, and the work was deemed sacred, likely accompanied by singing.

Gimbutas arrived at these conclusions upon discovering that in locations housing ceramic workshops, there were also temples dedicated to Goddesses, alongside paintings of symbols associated with music and poetry. Often, if the structure was two-storied, one level would contain the workshop while the other housed a temple.

The importance of ceramics is dual: it is crucial for domestic chores, agriculture, and commerce. Large jars were utilized for storing water, liquids, seeds, and agricultural goods, while smaller jars held food, jewelry, and perfumes. Ceramics became indispensable in food preparation, facilitating baking, frying, and boiling, as well as the boiling of liquids and various other processes we now take for granted. In agriculture, the production of large jars enabled the storage of seeds for future planting and other items for both short and long term, thus enhancing food security. These jars also facilitated the trade of perfumes, spices, wine, oil, and, eventually, ceramics were used to craft oil lamps for illumination.

However, ceramics served an additional purpose: clay, being a pliable material, could be molded as desired and, with the application of fire, transformed into a durable and permanent object. This allowed for the creation of various figurines and models. With the advent of ceramic use, models of houses and temples emerged, along with figurines and new depictions of Goddesses. Moreover, ceramics offered a medium that could be engraved, painted, and decorated with symbols, functioning as an early form of abstract language. When the first forms of writing were developed, they were inscribed on clay tablets.

Indeed, the pottery from the ancient world invariably carries a non-utilitarian aspect. For instance, in the Yarmukian culture’s pottery, we observe numerous decorations, particularly on the jar rims, uniquely fashioned. Some decorative symbols are universal, recurring in various locales and Goddess cultures globally, including motifs like waves, chevrons (open triangles), grids, triangles, and lines, while others are unique to specific traditions. Thus, the advent of clay usage introduced a novel aspect to art and, by extension, to religious expression.

The question of who operated in these workshops—which, as mentioned, were linked to Goddess temples—raises two possibilities. One theory suggests that specialized women (akin to priestesses) worked there, performing their tasks in exchange for compensation from the community. However, the more likely scenario is that pottery (along with other crafts) was a collective endeavor involving the village populace, particularly women; the entire community engaged in the work, sharing the responsibilities among themselves. This approach necessitated mobilization, coordination, and a shared commitment. In essence, starting from the 7th millennium, the Ceramic Period fostered the tradition of communal craft workshops, encompassing activities like weaving, spinning, pottery, lime production, and agricultural work. While this practice existed previously, the advent of pottery significantly enhanced it.

Women were adept at organizing and collaborating. Presently, in African villages, it’s common to find women banding together for agricultural tasks, crafts, and household endeavors. One could envision various groups of women within a village, each group dedicated to a specific craft such as pottery production in a designated hut, basket weaving, or cloth weaving. If women initially undertook the agricultural duties, the periods between farming seasons afforded them time for other crafts like weaving clothes and baskets. Regarding childcare, it was customary for children to accompany their mothers during these activities, a practice still observed in African villages today. Some children were cared for collectively by a woman or girl from the extended family. The Goddess served as the protector of crafts, agriculture, home, and family life.

What roles did the men fulfill? They, too, collaborated in groups, primarily on projects involving construction and other demanding physical tasks. They constructed the village’s central public house, excavated wells, tilled the fields, and occasionally hunted. However, organizing and coordinating village life, addressing the community’s needs and adapting to the seasons, likely fell to the women. A council composed of elderly women, priestesses, and shamans, who possessed the tribe’s wisdom, possibly played a key role in governance, and might have sought insights from a witch or prophetess. Furthermore, there was the circle, a village assembly inclusive of both genders. The distinguishing factor of Goddess culture societies, compared to contemporary African village societies, lies in the probable existence of a female-centric governance and religious structure, centered around Goddess worship and a matriarchal framework.

The social framework within ancient matriarchal societies was markedly different from the patriarchal structure prevalent in today’s society. In our contemporary society, there is not only a division of roles but also a division of wealth, creating a hierarchical pyramid topped by the affluent and powerful or the elite. This structure necessitates the concept of management and the role of a manager. Conversely, in Neolithic societies (Goddess culture), social order seemed to emerge organically, underpinned by an invisible network linking people with the cycles of nature, animals, plants, and the energies of the earth and sky. Individuals felt integrated into a larger, orderly whole, naturally acting in harmony without the necessity for rigid organization; this innate coordination stemmed from shared values and intrinsic motivation. In instances of ambiguity, resolution was sought through the circle or sage elderly women who, guided by the spirit of the Goddess, provided counsel to the assembly of priests and priestesses. While this description idealizes a scenario that may not have fully existed, the absence of warfare during this period, the prevalence of female figurines, and the connection of craft workshops with temples offer insights into the era, allowing us to infer aspects of societal organization with a degree of probability.

The figurines uncovered and the architectural layout of the villages suggest that, despite a communal social structure, each individual had their own dwelling and possessions, thereby bearing personal responsibility for themselves and their immediate environment. This is deduced from the prominent eyes featured in the sculptures, interpreted as symbols of alertness, vigilance, and attentiveness. However, these are not merely eyes but are depicted in the form of wheat grains (or date kernels), indicating a call for awareness and vigilance towards nature and agricultural practices as well. There is a harmony between nature and humanity, with the community being propelled by this interconnectedness. It appears that the large villages of the Goddess era were in tune with the spirit of the great mother, receiving guidance on their growth, prosperity, and future paths.

The Ceramic Period (6,400-4,500 BC) marks an era of widespread settlement across Israel, with the essence of the Goddess harmonizing the land under her guidance. In the initial 600 years following the advent of pottery, a sophisticated culture of stone and ceramics emerged, known as the Yarmukian culture, with its heartland located at Shaar Hagolan in the Jordan Valley. This development followed a phase where settlements were predominantly in the mountains (Pre-Ceramic Period B), leading to a return to the fertile valleys.

Shaar Hagolan Yarmukian Culture

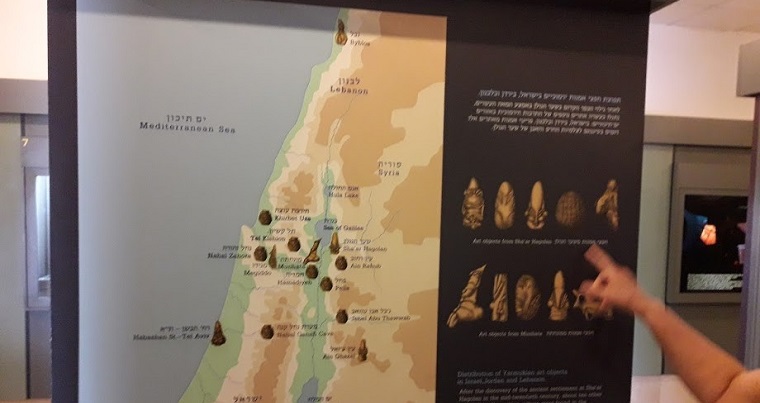

Shaar Hagolan is a kibbutz situated in the central Jordan Valley, close to the Sea of Galilee and at the meeting point of the Yarmuk and Jordan Rivers. Within the kibbutz’s fields, archaeologists uncovered a vast settlement over 8,000 years old, sprawling across an extensive 2,000 dunams. It is believed that the settlement housed between 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants, serving as a regional center. Initial excavations were conducted by Moshe Shtekalis in the 1940s, but the majority of discoveries and the publication about the “Goddess of Shaar Hagolan” were made by archaeologist Yosef Garfinkel. Furthermore, recent explorations have revealed more than 20 settlements throughout Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon, sharing cultural artifacts with Shaar Hagolan, suggesting a broad, interconnected civilization with Shaar Hagolan possibly at its core.

The excavated homes at Shaar Hagolan are spacious, segmented into numerous rooms, and feature an internal courtyard, making them ideal for extended family living. Some houses contain 10-20 rooms, with certain rooms arranged in pairs—one with a pebble floor and the adjacent one plastered. This setup hints at an underlying principle of duality, with some interpretations suggesting a division between areas for daily activities and others reserved for sacred household purposes. At the heart of these homes lies a substantial inner courtyard, concealed from the street and public areas. Previously, homes were considerably smaller, with a communal space beside each residence where most activities unfolded, effectively integrating personal living spaces with communal areas. Shaar Hagolan introduces, for the first time, a concept of private, open spaces isolated from external exposure, marking a significant social shift of the era.

Garfinkel interprets the architecture of the houses at Shaar Hagolan as reflecting three tiers of social organization: the nuclear family, the extended family or tribe, and the urban community. He proposes that the room pairs signify a bedroom and a storeroom for provisions, where a nuclear family—comprising parents and children—lived, raised, and stored their own food. Within the courtyards, water and milling facilities were available, indicating that food processing, and likely cooking, was a collaborative effort managed by the extended family, a practice believed to extend to craftsmanship as well. The homes were arranged following an urban plan, with paved and cobblestone streets discovered around them, suggesting a form of urban management.

A well constructed from large pebble stones was found on the edge of the settlement, signaling communal organization. The purpose of this 15-meter-deep well, showcasing remarkable technical skill, is uncertain, especially given its proximity to the Yarmk River, where water was readily accessible. It’s speculated that the well might have held religious or symbolic significance. Wells were considered sacred in the Celtic culture of Europe, symbolizing Mother Earth’s womb, suggesting a similar reverence could have existed here. A comparable well was unearthed at the Atlit Yam settlement, with earlier ritualistic wells also found in Cyprus.

Round storage pits located near the houses contained large jars, capable of holding up to 300 liters, likely used for storing grains and other agricultural produce. Flint tools and clay figurines were discovered alongside these urns, presumably placed there to protect the seeds through magical means, a practice observed in various cultural villages worldwide. The act of burying these urns might also carry magical significance, stemming from the belief that the earth Goddess’s power would imbue the wheat seeds with the energy to grow. This practice suggests that when the time came for planting, the seeds would already be familiar with the subterranean environment. Moreover, interring the seed jars in the earth symbolically linked them to the realm of the dead, who were thought to endow the seeds with the vitality to sprout.

At Shaar Hagolan, nearly 300 figurines were discovered, offering insights into the ancient Yarmukian religion, with almost all depicting women. These figurines, which can be as tall as 20 cm, are constructed from various clay body parts affixed to a sturdy clay core, forming a composite structure. The heads are elongated and pointed, with facial features attached to them, reminiscent of “Muppets.” The thighs and pelvis area of the legs are markedly thickened, about four times the thickness of normal legs, giving them an unusual appearance. The pelvis and buttocks are significantly accentuated and large, while the breasts are prominent but proportionately moderate. The surreal or exaggerated form of these figures has led archaeologists to view them as symbolic representations of the Goddess in a grotesque, perhaps even intimidating, guise, with the pronounced size of the buttocks and hips symbolizing fertility.

In certain figurines, the Goddess is depicted holding her left breast with her left hand, while her right hand rests on her right thigh. It is intriguing to observe that figurines from other regions of the world, such as Malta, and from other Yarmukian sites in Israel, like Bashan Street in Tel Aviv, present the Goddess in the same pose, with similarly exaggerated hips, reinforcing her association with fertility.

The figurines feature prominently large eyes, shaped like wheat sprouts, or alternatively, resembling the kernels of dates or coffee beans. Among these, 63 figurines have this distinct eye design, echoing the style seen in similar Goddess figures from the Balkans. The oversized eyes are interpreted by some as a general summons to awareness, while others view them as signifying a specific link to vegetation, highlighting the Goddess’s role as a guardian over the sprouting of wheat.

The figurines are notable for their prominent ears, which are depicted as elongated and feature what is considered the world’s earliest representation of earrings. On the abdomen of these figures, there is a distinct square marking where the navel is visible, suggesting that during the Goddess culture era, the navel was revered as a sacred body part, symbolizing the connection between a mother and her child via the umbilical cord. The depiction also gives the impression that the figure is clothed, with what appears to be a scarf wrapped around her neck.

While some interpret these figures as representations of extraterrestrial beings, I believe they are more accurately understood as symbolic. The Goddess figurines amalgamate human features, geometric patterns, elements of plants, animal parts, and objects resembling eggs. According to Marija Gimbutas’s interpretations in her books, these diverse elements symbolize various facets of the Goddess. The figurines typically measure about 10-15 cm in height, small enough to be carried in a pocket and transported from one location to another, which is precisely how they were used, serving as objects that bestowed blessings wherever they were taken.

At Shaar Hagolan, only one male figurine has been discovered, contrasting with the 153 female figurines. This male figure features a pointed head, eyes with a mischievous expression, and he is depicted covering his genitals with his hands. A similar statue was unearthed in Byblos, Lebanon, which also had a Yarmukian settlement. Additionally, at the Munhata site in the Jordan Valley, male figurines made of mud (rather than clay) were found, exhibiting distinct characteristics from those of the female figurines. These male figurines were constructed differently, featuring a narrow clay cylinder as their base, to which hands and male genitalia were attached, with emphasis placed on the legs and buttocks.

In addition to the clay Goddess figurines, several stone figurines were unearthed at Shaar Hagolan, including one referred to as the “Venus of Shaar Hagolan,” which is currently on display in the local museum. This small figurine depicts a female figure with prominently emphasized buttocks, resembling a bird, and divided in two by a slit. According to Gimbutas’ interpretation, this figurine embodies two characteristic representations of the Goddess. Firstly, it symbolizes the connection between human and animal figures (such as a bird) that signify the Goddess. Secondly, it represents the Goddess’s ability to reproduce, illustrated by the presence of two bulging buttocks, signifying the transformation from one to two.

In my view, the significance of the figurines is illuminated by their proximity to the urns used for storing agricultural produce, which were buried in round pits in the ground. This placement suggests a potential magical purpose—to safeguard grains and seeds from pests, possibly explaining the figurines’ large eyes (perhaps intended to deter pests, including rodents), especially when they resemble grains of wheat.

Another type of figurine discovered at Shaar Hagolan, showcased in its captivating museum (as well as the Israel Museum), consists of round pebbles adorned with engravings. These engravings often depict the contours of a human face, primarily featuring schematic renderings of eyes, and occasionally a mouth or nose. This art form, characteristic of the Goddess era, showcases an abstract thinking ability reflected in the simplified depiction of facial features. Remarkably, these pebbles are exclusively crafted from limestone, despite the abundance of basalt pebbles in the vicinity, suggesting that limestone held significance in this case. Garfinkel highlights that the most prominent feature of both the pebbles and clay figurines is the eyes, a common trait observed in figurines from other Goddess cultures worldwide.

According to Eliade, a stone embodies a hierophany, representing the appearance of a deity, due to its eternal quality and its resemblance to bones in our bodies, which persist after death. Consequently, throughout earlier and later periods, numerous statuettes of Goddesses were crafted from stone, with only a few fashioned from bone, underscoring the significance attributed to stone. In essence, stone figurines of Goddesses can serve to establish a connection between the individual holding them and the realm of spirits, aiding in the process of death and rebirth. Conversely, figurines and depictions of Goddesses crafted from clay can facilitate a connection between the individual and the world of life, assisting in matters of procreation, childbirth, and growth.

The pebbles adorned with human symbolism are not the sole type of artistic pebbles discovered. On occasion, pebbles are found engraved with lines, arranged both lengthwise and crosswise in a net-like fashion. Sometimes these lines form grids or squares, while in other instances, they take on the shapes of crosses, stars, or even waves. The meaning behind these engravings remains unclear, with various interpretations proposed. Some view them as elements of fertility or rain rituals, while others suggest they may be linked to initiation or learning processes. Additionally, there are those who propose that the engravings served as early seals, symbolizing ownership of property. According to Lewis Williams’ interpretation, geometric shapes represent an artistic expression of the initial stage in the shamanic trance experience, offering a potential explanation for their presence. Alternatively, Marija Gimbutas interpreted these signs as components of a language system.

The shape of the pebbles themselves appears to hold significance, particularly when considering their circular or egg-like forms. It is plausible that these pebbles were believed to possess magical properties, such that the act of engraving upon them manifested the desired outcome of the engraving itself. Additionally, in the construction of the public well at Shaar Hagolan, large pebbles (this time made of basalt) were utilized instead of more easily manageable stones. This choice likely stems from the perceived magical qualities attributed to pebbles in general, thereby reinforcing the hypothesis that the well was dug for ceremonial rather than purely practical reasons.

According to the alternative researcher Zecharia Sitchin, during the dawn of agriculture and human civilization, beings from advanced civilizations across the galaxy visited Earth, traversing the skies in small spacecraft resembling round, egg-shaped pebbles. Consequently, ancient civilizations depicted their gods in the form of pebbles. This “theory” offers an alternative explanation for the significance of pebble art at Shaar Hagolan and other sites worldwide. Additionally, one can examine pebble art from a spiritual-energetic standpoint, suggesting that humans reside within an energetic field known as an aura, which takes on the shape of an egg, akin to the pebbles.

Another discovery in Shaar Hagolan consists of numerous clay weight beads, akin to those utilized in weavers’ looms. This indicates that the people of the Yarmukian civilization operated weaving and clothing workshops, responsible for producing the fine garments depicted on some of the figurines. Evidently, they raised sheep and goats, utilizing their wool, and cultivated flax to extract fibers for weaving. Additionally, various types of weights were unearthed, likely employed in fishing nets spread across the Sea of Galilee or local streams, marking the first instance of widespread weight usage. Among the findings are necklaces crafted from seashells, some sourced from the Red Sea hundreds of kilometers away, suggesting that women adorned themselves with jewelry.

The inhabitants of Shaar Hagolan crafted sickles from carved wood, incorporating obsidian or flint stone knives within them. They utilized these tools to harvest wheat and tend to the fertile soil of the Jordan Valley, cultivating crops like wheat, barley, and a range of legumes such as beans, chickpeas, and lentils. Furthermore, alongside sheep and goats, they had already domesticated cattle (cows) and pigs, potentially employing oxen for plowing purposes.

The inhabitants of Shaar Hagolan fashioned tools from wood, stone, and bone, using them for tasks such as plowing or tilling the soil (a primitive pitchfork-like implement was discovered at the site). They crafted axes for felling trees and possessed the skill to construct furniture and buildings with wooden roofs. Additionally, they were adept at using bows and arrows, as well as employing sophisticated knives, scrapers, drills, mortars and pestles, grinding boards, ancient threshing boards, sickles, bayonets, hammers, anvils, and more. Among the findings were hard stones with grooves, which, according to one interpretation by Shtekalis, symbolize the female genital organ and serve as ritual accessories in a matriarchal culture. However, Garfinkel contends that these stones were used for grinding and sharpening tools.

Regrettably, only a fraction of the Shaar Hagolan settlement has been excavated thus far, and no public buildings or cemetery have been uncovered. The discovery of such structures in the future could provide invaluable insights into the culture’s beliefs, lifestyle, and social organization. In the meantime, we can attempt to glean additional information from other Yarmukian sites.

The Yarmukian culture

In the region of Israel and its environs, more than 20 sites are linked to the Yarmukian culture. It appears that Shaar Hagolan served as the capital of a civilization that extended over vast distances. These sites include the ancient settlement near Tel Megiddo, Yarmukian remnants found in Murbaat Cave in the Judean Desert and Nahal Kana Cave in Samaria, Yarmukian settlements discovered at Tel Pharaoh in Samaria, Bismun village in the Hula Valley, Tel Kashion in the Lower Galilee, near Kibbutz Hazorea in the Jezreel Valley, Horvat Utza in the Western Galilee, Munhata in the Jordan Valley, and various other locations in Israel and Trans Jordan. Primarily, Yarmukian settlements are established on new sites rather than previously inhabited ones.

Even on Habashan Street in Tel Aviv, traces of the Yarmukian culture have been discovered, including a notable statuette depicting a seated Goddess. In this representation, the Goddess is depicted holding her left breast in her left arm and placing her right hand on her right thigh, a typical posture. However, what sets this statuette apart is the presence of what appears to be snake-like fangs beneath her mouth. This suggests, firstly, a notion of danger associated with women from Tel Aviv. Additionally, it implies that during the time of the Goddess, one of the animals symbolizing sacred femininity (also in the Land of Israel) was the snake, perhaps due to its symbolic associations with regeneration and shedding skin.

The Yarmukian culture pioneered large-scale pottery production, fundamentally transforming daily life. In each household, a substantial water jar was a common feature in the yard, while vast jars buried in storage pits alongside the house held wheat and other agricultural produce. Excavations across Yarmukian sites nationwide have yielded a diverse array of utensils, ranging from spoons to 300-liter silo jars. Among these findings are jars adorned with distinctive decorations, such as fish bone motifs (resembling herring) arranged in horizontal parallel stripes or zigzag patterns, often painted in red or black. While decoration was not obligatory for everyday use, the presence of such embellishments underscores the significance of art and aesthetics within Yarmukian culture, suggesting the potential existence of a symbolic language encoded within these designs.

According to Garfinkel, the Yarmukian culture thrived from 6,400 to 5,800 BC, coexisting alongside separate cultures in Jericho and Nitzanim in the Negev. While these cultures shared similarities, they were distinguished by variations in pottery decoration. Concurrently, the Yarmukian culture flourished alongside other prosperous matriarchal societies worldwide, engaging in trade relations with them. This trade included the importation of various stones to Yarmukian sites in Israel, such as obsidian (sourced closest from Anatolia), marble, and alabaster, with some trade likely conducted via ancient seafaring vessels.

If we tally the number of discovered Yarmukian settlements along with those of the Jericho and Nitzanim cultures, an estimated 20,000 individuals resided in them. Considering potential undiscovered settlements and other forms of habitation, including villages of different types and nomadic tribes, Israel’s population at the time likely ranged from 50,000 to 100,000 people—a considerable figure. Regrettably, only three graves have been unearthed across all Yarmukian culture sites, providing limited insight into their beliefs regarding the afterlife. In these instances, the bodies were interred in a bent position and remained intact, with the heads still attached to the skeletons.

The equivalent of Vinca

Concurrently with the emergence of the Yarmukian Goddess culture in Israel, a similar culture called Starcevo arose in the Balkans around 6,200 BC. This culture later evolved into the Vinca culture, which thrived from approximately 5,700 to 4,500 BC. The Vinca culture has been extensively studied, thanks to the meticulous research conducted by Marija Gimbutas. Gimbutas provided an insightful interpretation of the spirituality and practices associated with the Vinca culture, making it intriguing to draw comparisons between these two civilizations.

Similar to Shaar Hagolan, the archaeological site of Vinca, located not far from Belgrade, exhibits orderly and paved streets, large and advanced houses, a developed material culture, and imported goods from distant regions. Vinca was a settlement with a population of at least 2,000-3,000 people, akin to Shaar Hagolan, which served as a cultural hub spreading across vast territories. The figurines discovered in Vinca share common features with those found in Shaar Hagolan, featuring prominent eyes and symbolic pottery decorations. It appears that these two settlements were part of the same cultural sphere, sharing mutual influences and characteristics.

Vinca, situated atop an artificial hill by the Danube River, reveals the remnants of hundreds of houses constructed from wood and mud, some measuring up to 80 square meters in size. These dwellings featured wooden frames with clay and mud walls, roofs composed of wooden beams layered with mortar and straw, and floors made of wooden beams covered with clay. The fireplaces, integrated into the houses, were equipped with cooking stoves and chimneys, serving dual purposes of cooking and heating. This ingenious design ensured a warm, smoke-free, and well-insulated environment, demonstrating remarkable efficiency in energy utilization. The sophisticated construction techniques employed in these houses, dating back 8,000 years, attest to the advanced knowledge of the ancients in building and heating technologies.

The houses discovered in Vinca, reveal a technological sophistication far beyond what was known in later periods. Remarkably, these dwellings were predominantly devoid of gardens, suggesting that a significant portion of the population may have been merchants or craftsmen, rendering Vinca as perhaps the oldest city in Europe. It’s conceivable that Vinca’s merchants traversed the Balkans, importing various goods to their cultural hub, with the prized obsidian stone from Romania’s Carpathian Mountains being among the most significant. This volcanic glass, renowned for its sharpness, remains utilized in surgeries today, yet the Vinca people employed it for a myriad of tools, including knives, razors, leather scrapers, and arrowheads. Operating from their central location near Belgrade, they distributed these products to the numerous Vinca settlements spanning the Balkans, from Greece to Romania.

In addition to obsidian, Vinca engaged in trade of locally produced paints, salt sourced from mines in Bosnia, and various stones vital to Neolithic (Goddess culture) practices. Vinca represented not merely a culture but a way of life permeating hundreds of settlements across the Balkans, spanning from Greece to Romania, Croatia to Bulgaria, over centuries. Situated at a pivotal crossroads in the Balkans, the urban nucleus of Vinca, positioned at the convergence of the Sava and Danube Rivers, served as a vital hub for both waterborne and terrestrial trade routes.

Agricultural techniques of the period underwent technological advancements, with an increased utilization of fertilizers contributing to enhanced yields and releasing some individuals to pursue specialized crafts. Within the Vinca culture, livestock such as goats, sheep, cows, and likely oxen for plowing, were raised and utilized, thereby reducing manual labor. Crops cultivated included wheat, barley, and flax, the latter serving as a source for clothing production. Surviving artifacts from excavations, such as statues and pottery, provide insights into the attire worn during this era.

In addition to trade and agriculture, the people of the Vinca culture, particularly women, demonstrated prowess in various crafts and excelled in their endeavors. They mastered the art of weaving textiles using an ancient loom they developed, producing garments such as socks, shirts, and pants. With adept skill, they drilled round holes in hard stones using a rotating reed drill and sand. They innovated in creating advanced ceramics, employing techniques such as repeated firing and glazing. Their craftsmanship extended to the creation of delicate and sophisticated stone tools, and notably, they were among the first in human history to produce copper, predating the Chalcolithic period. Evidently, copper held a symbolic significance for them, and they crafted axes and various implements from this material.

The Vinca culture, spanning across the Balkans, predominantly revolved around agriculture, yet it also boasted significant regional trade hubs. Evidently, the cohesive society was underpinned by intricate and sophisticated spiritual beliefs centered around the worship of the Goddess. We term it a “culture” due to the discovery of similar pottery and lifestyle remnants across numerous settlements in the Balkans, extending from Greece to Romania, suggesting their integration within a vast trade and exchange network, maintaining constant contact with one another.

The culture thrived in peace, untouched by conflict or war, resembling a utopian society that endured for 1200 years. Gimbutas, in her work “The Civilization of the Goddess,” cites Vinca as evidence supporting her assertion that ancient matriarchal utopian societies, far more advanced and sophisticated than commonly believed, once flourished.

In the museum at the Vinca site, a wide array of artifacts is showcased, including jewelry, precious stones, urns adorned with distinctive spiral decorations, bowls, vases, jars, stones with drilled holes, and numerous figurines depicting Goddesses. Some of these figurines were carried as talismans by travelers, symbolizing the protection of the Goddess during their journeys. Additionally, in certain houses, bull skulls with horns coated in a mud mask were displayed, echoing a symbol of the Goddess culture also found at Çatalhöyük.

All the houses in Vinca were uniform in size, indicating an absence of class distinction between the residents. Despite being a culture engaged in commerce, people were satisfied with meeting their own needs and did not pursue the construction of palaces or the accumulation of wealth for luxury living. Instead, they fostered connections with themselves, each other, and the Great Mother. This divine figure, symbolizing safety and prosperity, remained vigilant, providing assistance in times of need. Her unwavering gaze reflected a gentle approach, eschewing violence. Similarly, the Vinca culture rejected violence, as evidenced by the absence of remains indicating wars, fortifications, injuries, or weaponry. It is presumed that they adhered to a social organization, likely religious, which marginalized violent individuals and restrained destructive impulses, allowing their villages to thrive peacefully—a sort of Human golden age enduring for many years.

One of the most remarkable discoveries showcased in the local museum at Vinca is a black glazed clay jar topped with a lid fashioned in the likeness of a cat’s head (or a similar animal), complete with prominent eyes and ears. An archaeologist who participated in the excavations suggests that these large eyes and alert ears symbolize the vigilant and aware individual, embodying the ideal of this culture. Inside the jar were seeds intended for the next year’s crop. On both the jars and figurines, there are symbols that might represent an early form of writing. Over a thousand objects bearing this ancient script have been unearthed across the Balkans, predominantly on clay artifacts. Typically, only a single symbol appears on each item (although in Romania, tablets known as Tartarian Tablets have been discovered, featuring multiple symbols).

The dancer from Wadi Raba

Towards the end of the ceramic period in Israel, a new cultural phase emerges known as the Wadi Raba culture, named after a site near Rosh Haayin along one of the tributaries of the Yarkon River. This culture lasted for a thousand years (5,500-4,500 BC). While it might seem relatively brief from a prehistoric perspective, it actually spans a longer period than the time elapsed from the beginning of the Crusades to the present day. Archaeologist Joseph Garfinkel suggests that during this time, there were significant agricultural settlements, some of which continued the settlements of the Yarmukian culture. It was a period characterized by prosperous agricultural communities that remained largely unchanged for over 2,000 years.

One of the notable sites of the Wadi Raba culture is Ain al-Jarba in the Jezreel Valley, where a fascinating jar was unearthed featuring a relief of two dancers. Throughout history, the ancients often depicted dancers on jars due to their rounded shape, which allowed for a depiction of a circle of dancing figures, unlike flat stone slabs. Depictions of dancers from the era of the Goddess culture can be found in various locations worldwide, but the relief discovered on the jar from Wadi Raba marks the first of its kind found in Israel.

Dance held a significant role in the Goddess culture. Garfinkel delved into this subject [1] and demonstrated how numerous paintings, reliefs, and figurines of dancing figures, often representing Goddesses, have been uncovered in sites across the Middle East and the Balkans. According to Garfinkel, excavations at 140 sites dating back to the era of the Goddess culture in the Balkans and the Middle East, including Çatalhöyük, have revealed over 300 dance scenes.

At a site corresponding to the Wadi Raba culture period, located in Dumesti, Moldova, archaeologists unearthed 12 figurines depicting male and female dancers engaged in dynamic poses. Garfinkel suggests that these dances were integral to religious ceremonies, serving as a conduit to enter trance states to connect with the spirit world or to symbolize the cycles of life and death. He posits that these dances were likely accompanied by music and drumming, each playing a distinct role. The rituals appear to have parallels with those of contemporary “primitive” tribes in Africa, which induce states of trance and ecstasy.

The earliest depictions of dance in our region date back to rock paintings from 10,000 years ago, found at the Dhuweila site in eastern Jordan. Garfinkel notes that these paintings feature four dancing figures wearing masks and holding hands. Similarly, the dancers from Wadi Raba also appear to wear masks, suggesting that dance served as a means of communication with forces beyond human realms, akin to the shamanic tradition.

Williams, who examined the ancient rock paintings of the Bushmen [2], highlights the significance of dance as a tool wielded by shamans to induce altered states of consciousness, facilitating experiences of death (the departure of the soul from the body) and subsequent rebirth. He posits that dance also served as a method of healing. In his analysis, Williams draws parallels between the trance dances depicted in the rock paintings of Bushman shamans and those of the hunter-gatherer period, suggesting continuity in the utilization of such practices across different cultural contexts, including that of the Goddess culture.

During the Wadi Raba culture, pottery techniques advanced significantly. Jars were fired at higher temperatures, resulting in superior quality vessels with distinctive shapes, often adorned with intricate decorations. These jars were commonly found in black and red hues. Notably, for the first time, reliefs of animal and human figures appeared on the sides of the jars. Among these, the most renowned is undoubtedly the “dancer” figure from Wadi Raba.

The Ain al-Jarba (Wadi Raba) site lies on the northeastern side of the Menashe highlands. Apart from the dancer’s jar, another intriguing artifact was discovered—a jar with a wide opening adorned with a relief of a snake coiled within itself. The snake, as seen in the statuette from Bashan Street in Tel Aviv, was one of the symbols associated with the Goddess and also symbolized medicine. It is plausible that the jar containing the snake relief stored materials related to medicine. Conversely, the jar adorned with dancers may have contained items associated with dance rituals, possibly part of shamanic worship, such as narcotic plants.

The Wadi Raba culture exhibited a significant influence from the Halafian culture, primarily observed in northern Syria and Iraq. Notably, the Halafian Goddess figurines bear striking resemblance to those found in Vinca. These Goddess figures from the Halafian culture depict the deity holding both breasts with both hands and protruding them, akin to the sculptures discovered in Ain Ghazal. They share similar attributes with the Goddess figurines unearthed in Shaar hagolan, featuring prominent hips, accentuated pelvis, seated posture, and pointed lower limbs.

In addition to Ain al-Jarba, several other sites in the region are associated with the Wadi Raba culture. Jericho, Kabri, and Tel Tsaf in the Beit Shean Valley are among them. At Gesher, female figurines carved on flat stone slabs were discovered, along with pottery bearing similarities in decorations and artistic motifs to that of the Halafian culture. Furthermore, numerous stone seals adorned with Halafian geometric patterns were unearthed. These findings suggest the possibility of immigration from the regions of the Halafian culture in northern Syria and Iraq to the Land of Israel during that period.

Tel Tsaf

Israel’s diversity mirrors a microcosm of the world, encompassing various influences within its borders. Each region carries a distinct quality or energy, reflecting its unique characteristics. The Beit Shean Valley serves as a notable example of this phenomenon. Its ambiance differs from other parts of Israel, characterized by numerous springs, a profound connection to the land, and a sense of abundance. Some may even perceive an energy reminiscent of African or Egyptian landscapes.

The Beit Shean Valley occupies a strategic position as a crossroads, linking the Jezreel Valley and the Mediterranean Sea to the west, and the Jordan Valley and Transjordan to the south and north, respectively. Throughout history, this geographical importance led to the establishment of significant cities, with Beit Shean itself emerging prominently along the banks of Nahal Harod, at the valley’s most central and impressive location. However, the roots of habitation in the area trace back long before the rise of urban centers, with Tel Beit Shean being among the villages of the Wadi Raba culture during the 6th millennium BC. While little remains from this ancient period at the Tel Beit Shean site, further exploration of the Wadi Raba period directs attention southward to Tel Tsaf.

Tel Tsaf, situated near Kibbutz Tirat Zvi close to the Jordan River, stands out as one of the oldest and most significant sites in the Beit Shean Valley. Excavations have revealed remains of a remarkable settlement dating back 6,500 years, boasting a wealth of particularly intriguing artifacts. Among these discoveries are jars adorned with depictions of ancient birds and snakes, marking the first instances of such imagery found in Israel. Both birds and snakes held symbolic significance within Goddess cultures, as highlighted in previous discussions on representations of the Goddess. Their presence in the paintings, figurines, and decorative motifs of Tel Tsaf aligns with this broader context.

In Tel Tsaf, like in other villages influenced by Goddess culture, unique figurines of Goddesses have been uncovered. These figurines stand out due to their distinct violin-like shape, a feature not seen in earlier periods. The violin figurines found in Tel Tsaf and other settlements across Israel are characterized by their flat form, featuring a wide and expansive base representing the pelvis, with small breasts attached to the central body. These figurines typically possess a long, slender neck, although they often lack a head. Alongside these representations of Goddesses, excavations have also revealed figurines depicting “ordinary” animals such as dogs, cattle, and sheep.

In Tel Tsaf, much like in other villages influenced by Goddess culture, obsidian stones were discovered, likely imported from Turkey. However, alongside these, ancient copper was also found, primarily used for decorative purposes rather than toolmaking, suggesting possible origins from Armenia. Additionally, pottery indicative of the Tel Obeid culture from Mesopotamia was unearthed, indicating extensive trade networks and peaceful interactions with distant regions. Alongside imported goods and raw materials, numerous stamps were unearthed, suggesting a centralized economic administration and organizational structure within the community.

The village boasted spacious houses along with grain silos neatly arranged in the courtyards. Numerous artifacts such as grindstones, ovens, and various implements were unearthed, indicating that the settlement served as the agricultural hub of the region. Notably, among the discoveries were some of the earliest evidence of olive pits, suggesting the early domestication of olives in the area. Additionally, jars adorned with distinctive decorations featuring rhombuses and intricate networks of geometric lines were uncovered. Stone weights, similar to those found in Shaar Hagolan, were also found, likely used for spinning yarn, showcasing the advancement of crafts such as pottery, weaving, and spinning within the community.

The excavation at Tel Tsaf yielded the largest collection of prehistoric beads in Israel, comprising strings of hundreds of beads. Among them were beads crafted from ostrich eggshells, as well as others made from minerals in various colors such as green, red, orange, black, and white. In a burial site located near the silos, archaeologists discovered the remains of a woman adorned with a remarkable string of 1,668 beads encircling her hips. Positioned over her grave was a copper awl, suggesting her elevated status, possibly as a sacred woman. She may have held a significant role, such as a shaman overseeing the mystical craft of beadmaking or a priestess entrusted with safeguarding the community’s grain stored in the silos.

One notable discovery at Tel Tsaf is the presence of male infant skeletons interred within earthenware jars buried in the ground. Traditionally, archaeologists have interpreted such findings as sacrificial offerings, even when the skeletons were found beneath the floors of structures, as in the case of Tel Tsaf. However, Eliade offers an alternative explanation. According to him, ancient cultures perceived the soul as originating from the earth itself. In this worldview, Mother Earth bestowed strength not only upon human mothers but also upon their offspring. Therefore, women would give birth directly on the ground and place their babies upon it. When infants were small, they might be laid to rest in shallow holes covered with leaves, allowing them to absorb the earth’s elemental energies as they slept. This practice, rooted in the profound connection between fertility, birth, and the earth, symbolized a return to the nurturing embrace of Mother Earth, facilitating the cycle of rebirth. Similar customs, such as burying the placenta in the ground or passing infants through natural rock formations believed to possess magical properties, are also found in various primitive societies and enduring folklore traditions.

The practice of burying infants in jars may be linked to the storage of wheat kernels in similar vessels. In the belief system of these ancient cultures, the deceased played a crucial role in the germination and growth of wheat, symbolizing the control over what lies beneath the earth’s surface. Just as seeds buried in the ground hold the promise of new life, so too do the bodies of the departed. This perspective sheds light on the interment of infant skeletons, likely those who died naturally, within buried jars. Similar customs and beliefs are also found in archaic Greece, suggesting a broader cultural context for such practices. The predominance of male infants in these burials may reflect the belief that the earth, viewed as a feminine entity, required stimulation from the masculine force to facilitate fertility and growth.

Although located near the Jordan River like Shaar Hagolan, Tel Tsaf also features a significant discovery—a five-meter-deep well containing pottery fragments at its base. While archaeologists initially interpreted these fragments as merely broken vessels, there is speculation that they were intentionally shattered as part of ceremonial rituals. This notion gains support from the discovery of green stone beads and fragments near the well, suggesting a possible symbolic significance to the act of breaking the pottery.

[1] Garfinkel, Y. (1998). Dancing and the beginning of art scenes in the early village communities of the Near East and southeast Europe. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 8(2), 207-237

[2] Wallis, R. J. (2009). Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods