Extracts from my PhD – Generators of the Sacred in Charismatic Sacred Places, Haifa University. 2023

Introduction to the existence Generators of Sacredness

Upon analyzing sacred sites within Israel, it becomes evident that locations deemed charismatic by the populace, notably significant and renowned for their profound impact on visitors, share certain traits that facilitate the experience of the Sacred. For instance, the attribute of unifying duality serves as a catalyst for this experience of the Sacred. Consequently, an individual visiting sites endowed with such features is more likely to undergo a significant experience compared to visiting a conventional religious site. This potential for a meaningful encounter is contingent upon and manifested through the visitor’s conduct while at the site.

The tomb of Maimonides in Tiberias, for instance, attracts a similar number of visitors to that of the adjacent tomb of Rabbi Meir Baal Hanes (the Miracle Worker), yet research[1] indicates that visitor behavior at these sites diverges significantly. The Rabbi Meir complex is considered charismatic, perceived as a place of miracles and distinction, in contrast to the Maimonides tomb complex, which does not evoke such perceptions, despite Maimonides’ greater significance and fame compared to Rabbi Meir Baal Hanes. Thus, it can be generalized that the tomb of Rabbi Meir Baal Hanes qualifies as a charismatic holy site, while the Maimonides tomb is categorized as an ordinary holy site. The difference is attributed to the site’s layout and structure, the traditions and narratives it embodies, and, as I interpret, the presence of Sacredness generators, rather than its historical or religious significance alone.

This phenomenon is mirrored within Christianity; not every church garners equal attention or stimulates what is known as numinous feelings, those associated with an experience of Sacredness[2]. Consequently, a greater number of visitors report experiencing transcendence at the Mount Tabor church than at the church in Kfar Cana, despite both sites holding significant importance, being integral to any pilgrimage route in the Holy Land, and according to tradition, being locations of Jesus’ miracles. However, the Tabor Church, perched atop a mountain with a breathtaking view of the Jezreel Valley and constructed through a special process that allowed the planner creative freedom, contrasts with the Kfar Cana Church, which is nestled among other buildings and constructed in a standardized pattern common to churches worldwide.

The argument presented in this research posits a distinction between charismatic holy sites, which elicit a sense of Sacredness, and those that do not. This differentiation is attributed to the presence of Sacredness Generators within charismatic holy places. An examination of ten renowned holy sites across Israel, representing various religious and spiritual traditions and constructed at different times, illustrates the operation of these generators and confirms their presence. Each of the selected sites was designed and constructed with a degree of freedom, not strictly adhering to pre-established templates. This autonomy allowed designers to infuse their personal visions into the sites, distinguishing them from conventional holy places, such as standard mosques, churches, or synagogues. The design process facilitated the deliberate or inadvertent incorporation of Sacredness Generators into the site’s layout, endowing these places with charisma, or in other terms, rendering them “genuine” holy sites.

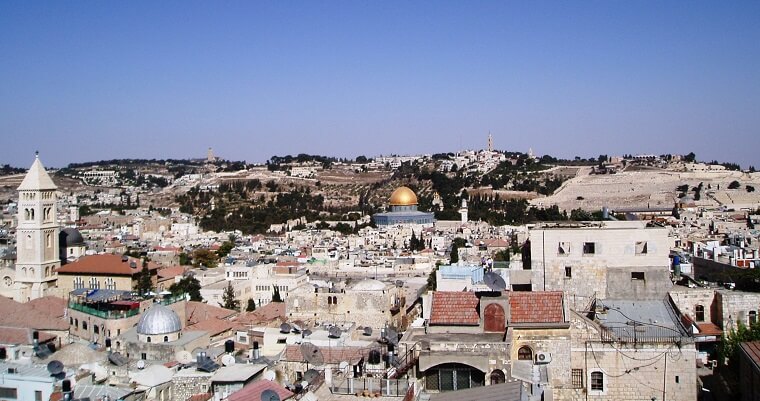

Three of the charismatic holy places located in Jerusalem are among the country’s most significant, well-known, and revered sites: The Wailing Wall, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and the Dome of the Rock. Extensive research and numerous publications have explored these sites, yet our current study aims to cast them in a novel light, demonstrating how Sacredness Generators enhance their allure and impact. Despite their differences, including distinct historical periods and sanctity within one of the three monotheistic religions, they share common Sacredness Generators. This shared aspect thus stimulates excitement and facilitates a religious experience for those who are receptive.

The Wailing Wall stands as the most sacred site for Jews globally, embodying a focal point of discourse, aspirations, and imagination. Similarly, the Dome of the Rock ranks among the top three sacred sites for Muslims worldwide, attracting attention, emotions, and discourse. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre holds the distinction of being the most sacred site for Christians around the world, drawing millions of pilgrims and serving as a model for churches across Europe[3]. Historically, it has captivated attention, feelings, and thoughts. This research argues that beyond their undeniable religious, national, and cultural significance, each site possesses Sacredness Generators that contribute to their popularity—elements that have often been overlooked by scholars.

The additional four sites selected for this study include: the tomb complex of Rabbi Meir Baal Hanes in Tiberias, renowned among Jews for its exceptional significance in seeking blessings and salvation; the Church of the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, distinguished by its unique location, design, and beauty; the Sacred Center (Zawiya) of the Sufi Shadhili Yashruti order in Acre, which is currently undergoing reconstruction and was chosen for its insight into the creation of a modern charismatic holy site; and Rujum Al-Hiri, a prehistoric stone circle in the Golan Heights, noted as the largest and most remarkable ancient sacred site, offering a perspective on the earliest stages of religious and sacred place construction.

A thorough examination and analysis of these sites, guided by theories from leading scholars in comparative religion as outlined in my prior research[4], yielded a list of attributes characteristic of charismatic holy places. Four such attributes—connecting center (often referred to as the world axis), unifying duality, fractal complexity, and the sublime extraordinary—were identified for further exploration. Given that these characteristics are not merely two-dimensional and activate in conjunction with the visitor’s interaction with the site, I have termed them Sacredness Generators.

Firstly, it’s crucial to make a distinction between two types of religiosity and religious experience, just as one differentiates between an ordinary holy place and a charismatic holy place. Religious experience is characterized in religious studies as an encounter with holiness, and in the psychology of religion, it is described as an internal moment of conversion, transcendence, and sanctification that occurs to an individual unexpectedly. In my perspective, this is akin to Abraham Maslow’s notion of peak experiences or Carl Jung’s concept of the “self” experience. I contend that certain places have the potential to initiate a process that may lead to a religious experience. However, since this experience does not manifest automatically or universally, the connection between a person and a place cannot be merely seen as a straightforward stimulus-response interaction. While insights from environmental psychology are valuable, a deeper exploration beyond its scope is necessary to fully grasp this phenomenon.

When discussing sacred spaces, it’s common to hear individuals express that “a sacred place is a place in nature” for them, acknowledging that many people encounter peak experiences in natural settings. Yet, it’s important to recognize that not all natural environments are created equal; different locations can elicit varied experiences. For instance, a person standing atop a cliff in the Judean desert witnessing the sunrise (or sunset) is more likely to experience a sense of Sacredness than someone standing on the desert plateau at midday. Similarly, certain holy places—those characterized as charismatic—possess a higher propensity to invoke the experience of Sacredness in individuals.

The notion that there are holy places traditionally stems from the belief that locations exert influence on individuals. However, the prevailing view today is that a holy place is defined by the occurrence of religious activities, but this perspective is not entirely accurate. Insights from the psychology of religion indicate that normative religiosity is tied to aspects such as identity, security, and morality, and stands apart from mystical religious experiences that involve encounters with the unknown. The routine practice of religious observance can sometimes distance an individual from the spontaneous experience of unity with everything. Therefore, within the scope of this study, religiosity is defined in terms of personal and mystical experiences of connection to a force greater than ourselves. Consequently, in this research, holy places are identified as those that impact us and have the potential to evoke mystical religious experiences, rather than being defined by their conventional religious designations.

Before delving into the Sacredness Generators present in charismatic holy places, it’s essential to understand the experience of holiness that a person may encounter—examining the nature of sacred feelings, how they manifest, our perception of the surrounding world, and our entry into mystical experiences. Transpersonal psychology suggests that individuals can access a higher level of consciousness. Carl Jung discussed the concept of the self, while Abraham Maslow spoke of peak and plateau experiences, among other contributions from various thinkers. This exploration into human consciousness sheds light on Mircea Eliade’s insights, a pivotal religious scholar of the 20th century, regarding the characteristics of Sacred places, the dichotomy between the Sacred and the Profane, and the manifestation of the divine in mundane places and times, which he termed “hierophany” (the appearance of divine power).

Eliade posited that humans are capable of experiencing two realms: the everyday, profane, and routine; and the eternal, sacred, and meaningful. He suggested that there are specific places and times where the eternal and sacred realm manages to permeate the profane and temporal realm, resulting in the manifestation of divinity (Hierophany). According to Eliade, the essence of being human, or “homo religiousus,” involves a quest for special moments and places that facilitate a connection to the Sacred. This pursuit of sacred places and times imbues life with meaning.

The notion that a location can significantly impact an individual might seem far-reaching, given the common belief that what truly matters is what resides within our hearts and minds, regardless of our physical surroundings. However, this perspective is fundamentally challenged by research in environmental psychology[5]. Evidence suggests that we are profoundly influenced by our environments, with which we identify, interpret, and through which we engage with the world, projecting onto them archetypal patterns inherent to our psyche. While some view the sanctification of a place as akin to idolatry, studies indicate that the deep bond between a person and a location is intertwined with self-perception, memory, and the mechanisms of cognition and consciousness. Broadening our understanding of this connection sheds light on how a charismatic holy place has the potential to catalyze religious experiences.

The aim of this research is to elucidate the manner in which charismatic holy places exert influence on individuals, exploring how specific Sacredness Generators within these sites resonate with them. By comprehending how people perceive and are affected by sacred places, we can gain deeper insight into the reasons behind their popularity and the role these sites play or could play in individuals’ lives. The presence of Sacredness Generators renders a place impactful.

The Wailing Wall serves as a prime illustration of the novel perspective introduced by this research, given that the majority of literature on the Wall traditionally focuses on its historical, political, religious, social, or cultural significance. In my prior research, I explored the Sacredness characteristics present at the Wailing Wall, such as the concept of axis mundi. The current study delves deeper into how these characteristics alter the visitor’s perception and facilitate a distinct kind of experience, extending beyond mere symbolism. It examines how Sacredness Generators effectively mold the lens through which individuals interpret their environment. This research outlines the manner in which a charismatic holy place can guide a person towards a religious experience via Sacredness Generators. It’s crucial to reiterate that this process is not automatic; it requires active engagement and a particular personality structure or mental state to be fully realized. The argument posits that beyond the Wailing Wall’s historical and religious importance, symbolizing the Temple and redemption, there lies an additional, until now unnamed, factor that has enhanced its charismatic allure in recent decades. The creation of the plaza in front of the Wall and the site’s layout have integrated Sacredness Generators.

Specific attributes, discernible through the interaction between an individual and a location, play a pivotal role in facilitating a religious experience. It is not merely a single attribute, but rather a collection of characteristics functioning together that resonate within us—these are the Sacredness Generators, such as the Generator of Sublime Extraordinary. The presence of something atypical within a site (like the immense stones of the Wailing Wall) aids in transitioning our experience from the profane and mundane to the eternal and sacred. However, this shift requires more than just any form of extraordinariness; akin to the principle that it takes gold to produce gold, the extraordinary must possess a quality of sublimity to effectively guide us towards the sacred.

To comprehensively grasp the operation of Sacredness Generators, it’s crucial to engage with the various domains of human religious experience and the process of visiting a sacred site. This endeavor necessitates drawing upon a wide range of academic disciplines that shed light on human perception and experience, particularly in relation to place. This includes not only religious studies but also environmental psychology, phenomenology, transpersonal psychology, and the psychology of religion. While basing research on such a broad spectrum of knowledge presents challenges, it establishes a robust foundation for the theory of Sacredness Generators. This approach renders their characterization more encompassing, principled, procedural, and fundamentally sound. It acts as the metaphorical Philosopher’s Stone, enabling a deeper understanding of holy places in the Land of Israel.

Although the characteristics (generators) of sacredness in holy places may be influenced by education and culture to a certain extent, at their core, they are objective rather than subjective. This objectivity is rooted in archetypes embedded within our perception of reality, archetypes that connect to the higher, transpersonal aspects of the human psyche. This assertion can be substantiated through phenomenology and religious studies, with some mechanisms functioning as described by Mircea Eliade in his seminal work, “Patterns in Comparative Religion”[6]. However, the existing theory has its limitations. To enhance our understanding and complete the picture of how religious experience and visiting a sacred place are interconnected, it is necessary to delve into environmental psychology, transpersonal psychology, and the psychology of religion, as well as into critiques of art and aesthetic experience.

This research suggests that any place constructed in alignment with the typology of Sacredness Generators is likely to foster a phenomenology of holiness, potentially eliciting an inner mystical religious experience, or in other terms, an experience of the Sacred, both internally and externally, for visitors who are receptive and prepared. This is analogous to the way individuals exposed to a work of art crafted according to specific principles (such as combinations of colors, proportions, perspective) may undergo an aesthetic experience, provided they are open and ready for it. While one might dismiss a Picasso painting as nonsensical, claiming “my child could paint better,” the experience of the Sacred, much like the experience of art, is fundamentally an objective, essential, and natural aspect of human existence. This is because it relates to our innate complexity and the manner in which we perceive reality.

The four Sacredness generators

The inaugural Sacredness Generator is identified as the sublime extraordinary. It is essential for it to be extraordinary, as the Sacred distinctly diverges from the profane. However, not just any form of extraordinariness suffices; it must embody the Quality of the Sacred. This generator has been termed “sublime” because the experience of the numinous is associated with a benevolent and supportive force. This quality facilitates an individual’s openness and the awakening of dormant capabilities, archetypal perceptions, and transformation, as outlined by William James (1842-1910).[7] Essentially, the sacred site undergoes a process of sublimation once the Numinous manifests through the extraordinary. This sublimation results from a shift in our perception, altering how we engage with the place.

In my previous research, it was noted that all the sites examined possess a distinctive feature often overlooked by scholars. For instance, the unique aspect of the Wailing Wall is the sheer size of its stones. The contention is that if the stones of the Wailing Wall were of a “normal” size, the site would not possess the same level of charisma, nor would it have captivated the Jewish popular imagination as profoundly as it has. The architect Yosef Schenberger, responsible for designing the Wailing Wall plaza, seemed to intuitively grasp the significance of highlighting this unique characteristic. Thus, he made the decision to lower the ground surface, revealing two additional rows of these extraordinary, giant stones.[8]

Research indicates that extraordinary events amplify religious inclinations. For instance, sudden thunderstorms have been observed to heighten the incidence of travelers reporting supernatural encounters and heightened religious sentiments[9]. Psychologists suggest that such occurrences prompt individuals to perceive reality from a fresh perspective. However, the extraordinary does not invariably produce a sense of sacredness; it can also provoke feelings of dread, as seen in experiences described as “The Uncanny.” Regardless of the response, these moments provide an avenue for the numinous to infiltrate the ordinary, becoming enmeshed with the place’s memory[10].

The sublime extraordinary serves as a pivotal Sacredness Generator, initiating a shift in how we perceive a place, potentially leading to a religious experience. In our daily lives, we often take our surroundings for granted, necessitating something to disrupt this norm and capture our attention[11]. The sublime extraordinary not only captures our attention but also influences our emotions, alters our sensitivity, and heightens our awareness. It activates an alternative mode of perception, enabling us to experience the numinous. Thus, the presence of an unusual element in a holy site—deemed the sublime extraordinary Generator—is crucial in rendering a sacred place charismatic and impacting its visitors.

The second Sacredness Generator identified is unifying duality. Carl Jung posited that the self represents the core of our personality, an elevated ideal towards which we must aspire to fulfill our destiny, characterized by the coming together of opposites. The journey of human life involves the merging of dichotomies—conscious with unconscious, persona with shadow, id with super-ego, among others. One emblem of the self is the mandala, which harmonizes the square and circle, symbolizing the “Philosopher’s Stone.” Jung believed that this synthesis of opposites engenders a transpersonal experience, absent in ordinary life. Thus, it can be argued that a defining feature of charismatic Sacred places is the Union of Opposites, which may manifest in various forms. An analysis of charismatic holy sites reveals the presence of duality within them. The contention here is that this duality fosters a process of reconciling opposites within oneself, being dynamic rather than static. Consequently, the Sacredness Generator of Unifying Duality involves an external duality that conceals an inner, unifying thread, revealing a hidden unity.

The Sacredness Generator of unifying duality is foundational to Mircea Eliade’s discussions on Hierophany (the manifestation of the divine) and Kratophany (the manifestation of power) within sacred spaces. Eliade presents the notion of two distinct realms: the mundane and profane versus the sacred and eternal. He maintains that, on occasion, the Sacred can manifest within the Profane—this phenomenon is identified as Hierophany, engendering a focal point where the cosmos is incessantly reborn (Axis Mundi). Eliade articulates that the objective behind every human settlement, temple, and sacred site is to forge such a nexus, motivated by the innate human yearning to transition from the fleeting to the everlasting, to reconnect with the Sacred (the Myth of Eternal Return).

The manifestation of the sacred within the profane represents a merging of these two realms (a unification of opposites). Rennie[13] interprets Eliade’s teachings as delineating two modes of perception within us, rather than as statements about ontological reality. Should we embrace his interpretation, Eliade’s concepts align seamlessly with Abraham Maslow’s theories[14] on peak and plateau experiences. Duality, in this context, is understood as a facet of human perception: we experience reality on one level and interpret it on another. This perspective is echoed in the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl[15] and others. Essentially, we embody both matter and spirit. The argument presented in our work is that physical manifestation of duality in sacred spaces—whether through duplication (such as two towers), the convergence of elements (a circle meeting a straight line, or the interplay of vertical and horizontal axes), or any other form—facilitates the integration of these dual modes of perception within us.

The third Sacredness Generator, termed “fractal complexity,” delves into depths that are not immediately apparent. Charismatic Sacred places are invariably expansive and intricate, forming a microcosm replete with hierarchy and internal dynamics. Such a sacred site must possess sufficient size and complexity to mirror the unconscious (and conscious) archetypes we hold regarding the world’s structure and human nature, especially from a spiritual and abstract perspective. The manifestation of this Sacredness Generator within a charismatic Sacred place is frequently represented through the site’s geometry and geometric patterns.

Generally, a fractal is a geometric shape that replicates the whole within its smaller components, revealing identical patterns at every scale, nested within each other. Within the scope of this research, the concept of fractal extends beyond mere geometry. Its application implies that a Sacred place reflects or embodies a reality greater than itself, such as the cosmos, the world, or the structure of the human, all perceived in abstract terms. A Sacred site encapsulates the abstract spiritual dimensions of the world as we perceive it. Our systemic categorization and understanding of the world engender a sort of archetypal framework we ascribe to it. This archetypal order is what is mirrored within the Sacred place and is what the Sacredness Generator of Fractal Complexity activates.

During my investigation of charismatic holy places in Israel, I identified this Sacredness Generator, which aligns closely with Eliade’s concept of the Sacred place as an Imago Mundi, suggesting that the holy site serves as a reflection of the universe and humanity. The holy place symbolizes both the world and humanity[16]. However, it’s crucial to clarify that the holy site does not merely symbolize or reflect phenomena such as the sunrise; instead, it re-enacts the process of sunrise, thereby evoking in an individual the impact of witnessing a sunrise. This effect is akin to experiencing abstract art, where one awaits the emergence of impressions and interpretations prompted by the artwork.

Put simply, the charismatic Sacred place mirrors the intricate patterns found in the numinous universe. This fractal-like quality awakens subconscious archetypes within individuals, which are linked to the religious experience. For instance, the sunrise embodies a spiritual archetype inherent within us—a transition from darkness to light, from potentiality to action. Hence, when the numinous essence of the sunrise is reflected in the architectural design of a holy place (such as the dual horizon depicted in the pylons of ancient Egyptian temples, symbolizing both physical and spiritual sunrise), it triggers a similar “sunrise” within ourselves. The Sacred place activates perceptual patterns akin to those evoked by witnessing the sunrise in nature, thereby elevating the Sacred Place to a moment of profound holiness.

The final Sacredness generator is the connecting center, also known as the world axis, which is a fundamental element in Eliade’s phenomenology of a holy place[17]. The world axis represents the central point that links heaven, earth, and the underworld, often symbolized by pillars, cosmic mountains, or sacred stones. It is at this center where continuous creation occurs and the connection between different planes of existence is established, leading to the manifestation of the sacred through the profane in an act of Hierophany. From my perspective, the center plays a crucial role in orientation, serving as a focal point that requires active engagement from the participant. Insights from environmental psychology indicate that orientation is the initial step in perceiving, interpreting, and engaging with a new environment. Moreover, the center serves as a connection not only between hypothetical planes of existence but also between individuals and their surroundings in a fundamental sense. It facilitates a connection to alternate modes of perception and states of mind within ourselves through focused attention, akin to the practice of meditation. Therefore, I have chosen to designate this generator as the connecting center.

Eliade’s theories emphasize that within every sacred place lies a center—an axis mundi—where creation undergoes continual renewal. Unlike other animals, humans construct and reconstruct their world constantly[18]. Thus, every dwelling serves as a microcosm of the universe, featuring a dynamically renewing center—an axis connecting various planes. While this aspect of holiness is commonly addressed in phenomenological discussions due to its widespread recognition, a deeper examination reveals that the construction of one’s world stems from an inner process of focus and attention.

Human attention functions like a spotlight, focusing on a singular point at any given moment. Consequently, the center represents more than just a geographical or physical location; it serves as a focal point for attention, signifying a shift in the way individuals perceive the world. The concept of the center operates within both sacred and profane contexts, influencing our interpretation of the surrounding environment. However, when the center connects individuals to other planes of existence, it becomes a Sacredness generator. Therefore, a true axis mundi transcends mere geographic centrality, encompassing a vertical connection between planes. Additionally, orientation towards the center, such as praying towards a holy place, imbues it with significance for the individual and may facilitate a connection with the divine. One can liken the process of prayer to a horizontal journey that transforms into a vertical axis upon reaching the center—the destination. This notion is echoed in the Islamic tradition of “The Israʾ and Miʿraj,” which recounts Muhammad’s nocturnal journey to the farthest mosque. The argument posited here is that proper centering, or orientation, can facilitate a connection between planes, leading to mystical religious experiences. This understanding challenges common misconceptions regarding Eliade’s teachings.

Given that we’re discussing a center that isn’t strictly geographical but rather serves as a point of orientation, it’s conceivable that the center could be something external to the Sacred place, such as the sun or even an abstract concept like a miraculous story. When orientation occurs, the focal point inevitably becomes the center. Considering that orientation is directed towards something beyond our immediate surroundings, the apparent duality between center and liminality in the phenomenology of Sacred places, as described by Eliade and Victor Turner, is reconciled. This duality is merely a matter of perspective.

The connecting center operates along both horizontal and vertical axes. It doesn’t inherently possess a center of its own; rather, it depends on an external point of reference from the observer. This external perspective facilitates a connection between planes. The Sacredness generator of the connecting center relates to the process of focusing, which broadens perception and allows the numinous to manifest through it, akin to the role of a mantra in meditation.

In summary, the four Sacredness generators often operate in tandem, interconnected and influencing one another. One way to conceptualize this is as follows: the sublime extraordinary captures our attention, guiding it towards the connecting center – the axis of the world. Surrounding the connecting center is the unifying duality, bridging the external and internal worlds, the Sacred and the profane. When the connecting quality of the center is activated, we are prompted by the fractal complexity of the place to recreate it anew according to archetypal sacred principles. We find ourselves no longer in the same place as before, but in the “abode” of the divine, presenting the opportunity for religious mystical experience. While the generators may function independently or in various configurations, their presence is essential for facilitating the perceptual shift necessary for such an experience.

Does the current research recognize the existence of sacred generators?

The thesis positing the existence of Sacredness generators in charismatic sacred places is fully articulated here for the first time, likely to provoke scholarly debate. Several foundational assumptions underpin this work, some of which may be contentious: firstly, distinguishing between ordinary sacred places and what I term “charismatic” sacred places is inherently challenging. Secondly, the link between visiting such places and experiencing religious mysticism remains unproven and is seldom addressed in religious studies, despite its implicit (and occasionally explicit) presence in the primary body of this field’s independent research.

Religious studies emerged as an independent field with the contributions of notable scholars such as William James[19], James Fraser[20], Emile Durkheim[21], and Rudolf Otto[22]. They contended that religious belief is an innate human faculty, advocating for the examination of religious phenomena from this perspective. However, the comprehensive exploration of religious phenomena and their connection to sacred sites was pioneered by Mircea Eliade[23], whose theories provide a foundational reference point for this work. It is important to recognize that Eliade approached these theories from a phenomenological rather than a mystical standpoint. In recent years, contemporary scholars have continued Eliade’s work, employing the phenomenological method to explore the manifestation of the sacred within the profane. Notable among them are Michael Rappengluk[25] and Rennie, who offer insights into and elaborations on Eliade’s teachings. In Israel, studies have also emerged that engage with Eliade’s characterizations, particularly his concept of the center as the world axis[26].

The current research draws partly from the insights of Eliade and other religious scholars. However, its innovative essence primarily stems from interdisciplinary studies that approach the topic from various angles. This multidimensional approach facilitates fresh insights and understandings. For instance, in anthropological studies, scholars like Victor Turner[27] and Clifford Geertz[28] have contributed significantly to comprehending religious phenomena and their potential relationship with sacred places.

In the realm of psychology, a burgeoning branch known as transpersonal psychology is illuminating the sacred in human beings and religious mystical experiences. This field owes much to the contributions of Carl Jung[29], who was influenced by both Eliade and James. Jung delved into the collective unconscious, archetypes, the self, and the psyche. Similarly, Abraham Maslow explored peak experiences and plateau experiences. Presently, several researchers are extending their work. For instance, Lionel Corbett is further developing Jung’s concepts[30], while Nicole Gruel is expanding upon Maslow’s ideas[31].

From the perspective of transpersonal psychology, it is possible to gain insights into the mystical religious experiences that can occur when visiting charismatic sacred places. These experiences involve the convergence of the sacred and profane planes, as Eliade describes, transpersonal psychology studies shed light on how the characteristics of a place facilitate this process. For instance, studies on peak experiences in natural settings[32] suggest that unique physical features of a location can enhance such experiences. This suggests the potential for peak experiences to be supported by the distinctive attributes of specific sacred sites. Transpersonal psychology also provides valuable insights into the process and experience of visiting a sacred place.

Psychology offers further avenues for examining the interaction between a charismatic sacred place and individuals, particularly through the emerging field of Religious psychology, also known as the psychology of religion. This area of study delves deeply into religious experiences, religiosity, and religious phenomena, seeking to explain and define concepts such as religious belief, the triggers for religious experiences, and the various forms of religiosity. Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle have authored a comprehensive book on this topic, which serves as a valuable reference in my research[33].

Another crucial perspective that psychology offers in understanding the relationship between individuals and their environment is environmental psychology. This field explores the psychological impact of the environment on individuals, focusing on the connection between people and their surroundings, as well as their perception of different places. Therefore, it holds significant relevance to our research. A seminal text on this subject was authored by four prominent experts: William Ittelson, Harold Proshansky, Leanne Rivlin, and Gerry Winkel[34], which I reference in my work. Additionally, various studies on human perception of places, particularly sacred ones, have been conducted by scholars such as Veikko Anttonen[35], Larry Shiner[36], Kim Knott[37], and numerous others.

Another discipline that significantly contributes to our comprehension of how we perceive places, including charismatic sacred ones, and the potential involvement of Sacredness generators therein to induce religious experiences is phenomenology. This philosophical approach was pioneered by German-Austrian philosopher Edmund Husserl[38] (1859-1938), German philosopher Martin Heidegger[39] (1889-1976), and French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty[40] (1908-1961). Their insights will serve as foundational elements in our study

Viewed from another perspective, art criticism and studies offer substantial contributions, particularly concerning aesthetic experiences and their relevance to the interaction between individuals and sacred places. Understanding how individuals perceive artworks and the impact of such encounters can provide insights into how Sacredness generators facilitate religious experiences. Noteworthy in this context are the works of Dora and Erwin Panofsky[41] and Wassily Kandinsky[42], as well as the collection of studies edited by Michael Mitias[43], which delve into the potential for aesthetic experiences and their phenomenology.

Numerous studies have explored holy places extensively, often focusing on their historical, geographical, cultural aspects. These studies offer valuable insights into the dynamics between individuals and their surroundings. Recently, there has been a growing body of literature examining the general characteristics of sacred places and their impact on human experience. While these studies partially complement Eliade’s phenomenology, they often fail to distinguish between charismatic and ordinary sacred sites, thus missing the essence of the matter. Additionally, research has delved into the experiences of individuals who visit these holy sites and the processes they undergo during their visits. Noteworthy in this regard are Eric Cohen’s studies[44], along with the works of Noga Collins-Kreiner, particularly her research on Christian[45] and Jewish holy places. These studies offer valuable quantitative and statistical data to support the theories presented in this work.

Last but not least, it is worth noting that there has been a recent surge in more focused studies on the characteristics, typology, and phenomenology of sacred places across various religions. These studies delve into sacred places within Christianity[46], Islam[47], Judaism[48], and the Baha’i religion[49]. Additionally, there are emerging research efforts focusing on specific sacred places in Israel[50] and around the world[51], as well as general studies exploring various characteristics of the Sacred. For instance, Emilie van Opstel’s book examines the subject of thresholds and doors in the ancient world[52]. In this context, Thomas Barrie’s comprehensive work on sacred architecture[53] is particularly noteworthy. Barrie views architecture as a mediator between the sacred and the profane, and given that most sacred sites are built environments, his insights are highly relevant to our research.

In conclusion, the existing studies on sacred places in Israel cover a wide range of topics including historical, political, sociological, geographical, and artistic aspects. While many of these studies offer valuable insights, they often lack a comprehensive understanding of the unique phenomenon of charismatic sacred places. This work introduces a new approach, which could be termed “sacred phenomenology,” aimed at comprehending and characterizing these charismatic sacred sites. It distinguishes between two types of sacred places and posits that certain places possess a special influence on visitors due to their deliberate design and inherent Sacredness generators. In the following chapters, we will delve into a detailed exploration of these generators and their nature

Comments

[1] קולינס־קריינר, נגה, המאפיינים והפוטנציאל התיירותי של עלייה לרגל לקברי צדיקים, דוח סופי מוגש למשרד התיירות, חיפה: אוניברסיטת חיפה, 2006.

[2] Otto, R. 1959. The idea of the holy: [an inquiry into the non-rational factor in the idea of the divine and its relation to the rational]. Penguin, Harmondsworth

[3] George Jeffery, A Brief Description of the Holy Sepulcher Jerusalem and Other Christian Churches in the Holy City: With Some Account of the Mediaeval Copies of the Holy Sepulcher Surviving in Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010

[4] בן אריה, זאב, מאפיינים של קדושה במקומות קדושים בישראל, עבודת מ.א. 2019

Ben arie, Zeev. Characteristics of Holiness in Holy Places in Israel, Thesis University of Haifa, 2019

[5] Ittelson, William H., Harold M. Proshansky, Leanne G. Rivlin, and Gary H. Winkel, An Introduction to Environmental Psychology, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974.

[6] מירצ’ה אליאדה, תבניות בדת השוואתית, תרגם: יותם ראובני, תל־אביב: נמרוד, 2003, עמ’ 17-15.

Eliade, Mircea. Patterns in comparative religion. U of Nebraska Press, 2022.

[7] ויליאם ג’יימס, החוויה הדתית לסוגיה: מחקר בטבע האדם, תרגם: יעקב קופליביץ, מהדורה שנייה, ירושלים: מוסד ביאליק. 1959, עמ’ 170.

James, W. 1950. The varieties of religious experience: a study in human nature. The Modern library, New York

[8] שמואל בהט, “‘להבדיל בין קודש לחול’: עיצובה של רחבת הכותל המערבי אחרי מלחמת ששת הימים ומשמעויותיו”, קתדרה 174 (תש”ף), עמ’ 181-155

Bahat Shmuel, Lehavdil Ben Kodesh Lehol, Ḳatedrah be-toldot Erets-Yiśraʼel ṿe-yishuvah 174, 155–181.

[9] Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi and Michael Argyle, The Psychology of Religious Behavior, Belief and Experience, London: Routledge, 1997, p. 84

[10] Dylan Trigg, The Memory of Place: A Phenomenology of the Uncanny, Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2012, pp. 12-17

[11] William H. Ittelson, Harold M. Proshansky, Leanne G. Rivlin, and Gary H. Winkel, An Introduction to Environmental Psychology, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974, p. 91

[12] קרל גוסטב יונג, פסיכולוגיה ודת, תל־אביב: רסלינג, 2005, עמ’ 128.

Jung, C. (2017). Psychology and religion. In Religion Today: A Reader (pp. 272-274). Routledge.

[13] Bryan S. Rennie, Reconstructing Eliade: Making Sense of Religion, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1996, p. 13

[14] Abraham H. Maslow, Religions, Values, and Peak-Experiences, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1964, p. 65

[15] אדמונד הוסרל, על הפנומנולוגיה של הבין-סובייקטיביות: מבחר כתבים, תרגמו: שמאי זינגר ואלעד לפידות, תל־אביב: רסלינג, 2016, עמ’ 66-63.

[16] Jean Holm and John Bowker (eds.), Sacred Place, London: Continuum, 1998, p. 114

[17] מירצ’ה אליאדה, תבניות בדת השוואתית, תרגם: יותם ראובני, תל־אביב: נמרוד, 2003, עמ’ 222.

Eliade, Mircea. Patterns in comparative religion. U of Nebraska Press, 2022.

[18] מירצ’ה אליאדה, המיתוס של השיבה הנצחית: ארכיטיפים וחזרה, תרגם: יותם ראובני, ירושלים: כרמל, תש”ס, עמ’ 18. Eliade, M. 1954. The myth of the eternal return. Pantheon Books, New York

[19] James, W. 1950. The varieties of religious experience : a study in human nature. The Modern library, New York

[20] Frazer, J.G. 1952. The golden bough : a study in magic and religion. The Macmillan company, New York.

[21] Durkheim, Émile and Cladis, M.S. 2001. The elementary forms of religious life. Oxford University Press, Oxford

[22] Otto, R. 1959. The idea of the holy : [an inquiry into the non-rational factor in the idea of the divine and its relation to the rational]. Penguin, Harmondsworth

[23] Eliade, Mircea. A history of religious ideas volumes 1 + 2 +3. University of Chicago Press, 2014. And others

[24] Bryan S. Rennie, Reconstructing Eliade: Making Sense of Religion, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1996,

[25] Michael A. Rappenglück, “Cave and Cosmos, a Geotopic Model of the World in Ancient Cultures”, in Juan Antonio Belmonte and Mauro Peppino Zedda (eds.), Lights and Shadows in Cultural Astronomy: Proceedings of the SEAC 2005, Isili, Sardinia, 28 June to 3 July, Isili: Associazione Archeofila Sarda, 2005, pp. 241-249; idem, “Constructing Worlds: Cosmovisions as Integral Parts of Human Ecosystems”, in Jose Alberto Rubino-martin, Juan Antonio Belmonte, Francisco Prada, and Anxton Alberdi (eds.), Cosmology Across Cultures: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at Parque De Las Ciencias, Granda, Spain 8-12 September 2008, Astronomical Society of the pacific, 2009, pp. 107-115

[26] Zali Gurevitch and Gideon Aran, “Never in Place: Eliade and Judaïc Sacred Space”, Archives de sciences sociales des religions 39 (1994), pp. 135-152; Benjamin Z. Kedar and R.J. Zwi Werblowsky (eds.), Sacred Space: Shrine, City, Land: Proceedings from the International Conference in Memory of Joshua Prawer Held in Jerusalem, June 8-13, 1992, New York, NY: New York University Press, 1998

[27] Victor Turner, “The Center out There: Pilgrim’s Goal”, History of Religions 12 (1973), pp. 191-230

[28] Clifford Geertz, “Religion as a Cultural System”, in Michael Banton (ed.), Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion, London: Routledge, 1966, pp. 1-46 (rep. 2004)

[29] Jung, C. (2017). Psychology and religion. In Religion Today: A Reader (pp. 272-274). Routledge.

[30] Lionel Corbett, The Religious Function of the Psyche, London: Routledge, 1996

[31] Nicole Gruel, “The Plateau Experience: An Exploration of Its Origins, Characteristics, and Potential”, Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 47 (2015), pp. 44-63

[32] Matthew G. McDonald, Stephen Wearing, and Jess Ponting, “The Nature of Peak Experience in Wilderness”, The Humanistic Psychologist 37 (2009), pp. 370-385

[33] Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi and Michael Argyle, The Psychology of Religious Behavior, Belief and Experience, London: Routledge, 1997,

[34] Ittelson, William H., Harold M. Proshansky, Leanne G. Rivlin, and Gary H. Winkel, An Introduction to Environmental Psychology, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974

[35] Veikko Anttonen, “Space, Body, and the Notion of Boundary: A Category-Theoretical Approach to Religion”, Temenos 41 (2005), pp. 185-201

[36] Larry E. Shiner, “Sacred Space, Profane Space, Human Space”, Journal of the American Academy of Religion 40 (1972), pp. 425-436

[37] Kim Knott, “Spatial Theory and the Study of Religion”, Temenos 41 (2005), pp. 153-184

[38] Ferrarello, S. and Applebaum, M. 2014. Phenomenology of intersubjectivity and values in Edmund Husserl. Cambridge. Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, England

[39] Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, tr. Joan Stambaugh, revised by Dennis J. Schmidt, Albany, New York: SUNY Press, 2010

[40] Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, Phenomenology of Perception, tr. Colin Smith, New York: The Humanities Press, 1962.

[41] Dora Panofsky and Erwin Panofsky, Pandora’s Box: The Changing Aspects of a Mythical Symbol, New York: Pantheon Books, 1956

[42] Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Bexar County, TX: Bibliotech Press, 2012

[43] Michael H. Mitias (ed.), Possibility of the Aesthetic Experience, Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1986

[44] Eric Cohen, “A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences”, Sociology 13 (1979), pp. 179-201

[45] Collins-Kreiner, Noga, et al. (eds.), Christian Tourism to the Holy Land: Pilgrimage during Security Crisis, Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate, 2006.

[46] Robert Austin Markus, “How on Earth Could Places Become Holy? Origins of the Christian Idea of Holy Places”, Journal of Early Christian Studies 2 (1994), pp. 257-271

[47] Karen Armstrong, “Sacred Space: The Holiness of Islamic Jerusalem”, Journal of Islamic Jerusalem Studies 1 (1997), pp. 5-20

[48] Gurevitch and Aran, “Never in Place: Eliade and Judaïc Sacred Space”

[49] Michael Steven Meizler, Baha’i Sacred Architecture and The Devolution of Astronomical Significance: Case Studies from Israel and the Us, Thesis Diss., University of Arkansas, 2016

[50] Nurit Stadler and Nimrod Luz, “The veneration of womb tombs: Body-Based Rituals and Politics at Mary’s Tomb and Maqam Abu al-Hijja (Israel/Palestine)”, Journal of Anthropological Research 70 (2014), pp. 183-205

[51] Myra Shackley, “Space, Sanctity, and Service: The English Cathedral as Heterotopia”, International Journal of Tourism Research 4 (2002), pp. 345-352

[52] Emilie M. van Opstall, Sacred Thresholds: The Door to the Sanctuary in Late Antiquity, Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018

[53] Thomas Barrie, The Sacred In-Between: The Mediating Roles of Architecture, Abingdon: Routledge, 2010