This article discusses Christian sites on the Mount of Olives within the context of the Via Palma pilgrimage route of the Middle Ages, as well as their broader significance. It covers locations such as Mary’s Tomb, Gethsemane, the Place of Ascension, Pater Noster Church, and the Santa Ana Church and Complex.

Mount of Olives

The situation in Jerusalem during the 13th century was intricate. For a brief span of 16 years (1229-1244), Muslims governed the Temple Mount while Christians controlled the rest of the city—a dynamic reminiscent of contemporary times. This period saw amicable relations between Muslims and Christians, fostering safe travel routes and enabling the development of the Via Palma pilgrimage route, which encompassed visits to Christian sites in Jerusalem.

After exploring the sites on Mount Zion, pilgrims descended the very steps traversed by Jesus from the room of the Last Supper to the area of Gethsemane, where he endured his most arduous hour before being apprehended by soldiers. Today, the “All Nations” Church occupies the spot where he grappled with the “Dark Night of the Soul.” Although the small Crusader and Byzantine churches that once stood there have vanished, the ancient olive trees endure, some dating back to the time of Jesus.

The pilgrims embarked on a profound journey, visiting significant sites on the Mount of Olives and its surroundings. They paid homage at Gethsemane and Mary’s Tomb nestled at the mountain’s base. Climbing to the site of the present-day Dominus Flevit Church, they stood opposite the Dome of the Rock, where Jesus wept over Jerusalem. Ascending the mountain’s summit, they reached the place of ascension, where Jesus ascended to heaven.

En route to Gethsemane, pilgrims also visited key locations in the Jehoshaphat Valley (Nahal Kidron), including Absalom’s Tomb, the Tomb of Zechariah, the Tomb of Benei Hezir, and the Gihon Spring. Each site held profound emotional and spiritual significance, resonating deeply with the pilgrims who identified themselves as true Israelites. The Shiloh Pool, in particular, held a special association with Jesus, further enriching their pilgrimage experience.

Descending the Kidron Valley, pilgrims encountered the Ben Hinnom Valley, where the monastery of Akeldama, or the Field of Blood, stood. This field was purchased by Judas Iscariot with the thirty pieces of silver he received for betraying Jesus. It served as a burial ground for those who perished along the pilgrimage route and housed a monastery, owned by the Hospitallers. The soil of the Field was deemed sacred, believed to aid in the resurrection of the dead. Pilgrims often took handfuls of this soil back to Europe to inter with their own remains, viewing the pilgrimage to Jerusalem as a preparation for death. They brought death shrouds or purchased clothing and souvenirs in Jerusalem to accompany them to the grave and into the afterlife.

During Jesus earthly life, significant events happened on the Mount of Olives. He entered Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives riding a white donkey, symbolizing the anticipated Messiah. Throughout the holy week leading to his crucifixion, he lodged in Bethany (Al-Eizariya) on the Mount of Olives, where he resurrected Lazarus. Additionally, he dried figs in Bethphage and wept over Jerusalem’s fate on the slope of the Mount of Olives. His final hours were spent at the foot of the mountain in Gethsemane. It’s no wonder that after his resurrection, he returned to the Mount of Olives to impart teachings to his disciples and ascend to heaven from there.

In this context, it’s worth noting that pilgrims on the “Via Palma” held great admiration for the architectural magnificence of the Muslim Dome of the Rock, which Crusaders referred to as the “Templum Domini.” They viewed it as a representation of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. The stark contrast between this awe-inspiring Muslim site, which they could not enter, and their own sacred places likely reminded them of the perceived spiritual conflict between Christianity and what they considered the entrenched and corrupted rabbinic Judaism of Jesus’ era. This sentiment resonates with Jesus’s lament over Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, as recounted in Luke 19:41-44, “If you, even you, had only known on this day what would bring you peace—but now it is hidden from your eyes. The days will come upon you when your enemies will build an embankment against you and encircle you and hem you in on every side. They will dash you to the ground, you and the children within your walls. They will not leave one stone on another, because you did not recognize the time of God’s coming to you.” Today the Dominus Flevit Church is at the place of weeping.

In Bethphage, there stood a Crusader church that housed a square rock believed to be the one Jesus climbed onto to mount the donkey for his entry into Jerusalem. Paintings adorned the rock, depicting scenes of Jesus’s disciples procuring the donkey, his triumphant entry into Jerusalem, and the resurrection of Lazarus. Palm Sunday processions from this site to the Church of Santa Ana were a significant tradition, possibly accompanied by symbolic processions on other days, akin to the Via Dolorosa today. Today, a splendid church constructed by the renowned church architect Barluzzi stands at this location.

Bethany (Al-Eizariya) held a special significance in the Christian tradition as the home of Martha and Mary, where Jesus stayed during the Holy Week preceding Easter. It was here that Mary Magdalene anointed Jesus with oil, and where he performed the miraculous resurrection of their brother Lazarus. Pilgrims would visit the remains of the magnificent church constructed by Melisinda in honor of Mary and Martha, and they would also explore the convent established by French nuns in the vicinity. Many would enter the empty tomb of Lazarus, echoing the hope for their own resurrection. They would recite the words of Jesus: “I am the resurrection and the life. The one who believes in me will live, even though they die; and whoever lives by believing in me will never die” (John 11:25-26).

Barluzzi’s architectural legacy on the Mount of Olives comprises four remarkable churches: the church in Bethphage, the church in Bethany, the Church of All Nations in Gethsemane, and Dominus Flevit Church. Each of these structures encapsulates a specific mystery linked to the events in the life of Jesus. Barluzzi was keenly attuned to the necessity of reenacting the Christian narrative in its original setting. Drawing inspiration from the resonance of Jesus’ voice across the mountains and valleys of Israel, he crafted architectural and artistic plans aimed at evoking religious fervor. Indeed, contemporary pilgrims attest that within the churches conceived by Barluzzi, they find themselves able to pray with genuine devotion.

Barluzzi deliberately aimed to cultivate a sense of holiness. In his own words: “In Palestine every holy place has a direct reference to a definite mystery of the life of Jesus. It is natural, therefore, to avoid the general type of architecture that constantly repeats the same designs, and instead to design the art so as to express the feeling called by that mystery. This is so that the faithful, upon entering the temple, will be able to easily construct in their thoughts the story of the gospel and concentrate in their meditation on thoughts appropriate to the mystery presented there, instead of choosing the art first and bending all other things to fit it. I think it is more appropriate to first establish the basic religious concepts of holy places for which the temple is will be built, and adapt the architecture to them.”

Sometimes he employed comparative religious studies terminology to elucidate his work: “In order to achieve the greatest and most moving artistic effect, an effort must be made to achieve maximum simplicity of line. In search of universal and profound qualities that would give maximum results with a minimum of commotion, almost an attempt to translate into architecture the grandeur and simplicity of The Holy Scriptures. These works were done more with the heart than with science, looking for the soul of things.”

Church of Gethsemane

At the bottom of the Kidron Valley, at the lowest point in Jerusalem, lies an olive grove known as “Gethsemani”. It was to this place that Jesus retreated after the Last Supper, accompanied by three of his disciples, to grapple with his impending fate and seek solace in prayer. Facing the imminent arrival of the soldiers and the looming prospect of crucifixion, he wrestled with his human nature and his divine purpose. This pivotal moment in his life is commemorated by a church built on the site, originally established during the Byzantine period and subsequently rebuilt by the Crusaders, eventually destroyed. In the 20th century, Barluzzi built a wonderful new church called “All Nations Church” in the same place.

The Christian mystery associated with Gethsemane is called “the dark night of the soul” or the “Agony in the Garden” Mystery. It is one of the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary, a challenging moment that we all may face in life, during which we are called upon to find inner strength. In this place, Jesus demonstrated human weakness for the first and last time in his life. Despite knowing what was to come, he struggled intensely, sweating blood and water, and pleaded with God to spare him from the “cup of poison”. He asked his disciples to stay awake and be with him during this dark hour, but they succumbed to sleep, illustrating the frailty of the flesh in contrast to the desires of the soul. This moment is significant not only for its personal anguish but also as a representation of the universal human struggle. Jesus, by enduring this agony, took upon himself the burden of all human suffering.

Jesus possessed both divine and human natures, with his human side reluctant to face the suffering and agony foreseen. This part of him recoiled at the thought of enduring the cross’s pain. Nonetheless, his divine essence prevailed, leading him to embrace the crucifixion as a necessary sacrifice, aligning with God’s will.

Upon the arrival of the soldiers, accompanied by Judas Iscariot, to apprehend Jesus, Judas betrayed him through a kiss on the cheek. This act of betrayal, marking Jesus for arrest with a pre-arranged signal, compounded the treachery against his teacher and benefactor. As the disciples stirred, prepared to defend him, Peter even went so far as to sever a soldier’s ear. Yet, Jesus urged them to forego resistance, advocating for acceptance of God’s will. He counseled against retribution, calling for a response rooted in love rather than vengeance.

The “Church of All Nations” in Gethsemane, crafted by Barluzzi, stands as a testament to his architectural genius and marks his first major achievement. Central to his architectural philosophy is the fusion of events from Jesus’ life, as viewed through a Christian lens, into the very fabric of the church’s design. Barluzzi’s churches are conceived not merely as structures but as vessels of divine inspiration, each narrating the sacred mysteries of Jesus’ life. His aim was to guide visitors towards a profound, enlightening encounter through the interplay of architecture and art, unveiling the lessons embedded in these divine mysteries for our lives.

Within the churchyard, ancient olive trees stand sentinel, while the interior houses the rock upon which Jesus is believed to have leaned in Gethsemane. Barluzzi’s design and artistic expression within the church aim to embody the concept of the “dark night of the soul,” portraying not an individual’s struggle but a collective human ordeal. Emphasizing this theme, the pediment above the entrance features a mosaic. Here, on the right side, a woman clad in black cradles a deceased child, representing Europe in mourning for her lost children, casualties of the First World War. Behind her, figures from various nations who contributed to the church’s construction stand in solidarity. Erected in the aftermath of the war by countries once in conflict, the church serves as a beacon of peace and reconciliation.

Opposite this scene, the pediment’s mosaic presents ancient philosophers like Socrates and Virgil, depicted in states of distress, with one among them holding a book inscribed with the word “ignorance.” At the pediment’s center, a figure resembling a woman-angel extends her arms in a gesture that is part lamentation, part invitation to enter, bridging sorrow with welcome. Hovering above, a depiction of God and angels bear a book marked with the Alpha and Omega symbols, signifying the beginning and the end. Beneath the pediment, the architrave bears the inscription: “During the days of Jesus’ life on earth, he offered up prayers and petitions with fervent cries and tears to the one who could save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverent submission.” (Hebrews 5:7), drawing a connection between the biblical narrative and the themes of suffering and hope reflected in the church’s design.

The Church of Gethsemane, a testament to Barluzzi’s architectural brilliance, embodies poetry crafted from stone. Entering this sacred space immerses visitors in an atmosphere reminiscent of a dark, untamed wilderness. The church’s dark purple windows, fashioned from alabaster, filter in a somber light that bathes the interior in shadows—a deliberate nod to Christian liturgy where purple denotes repentance. Darkness is a prevailing theme here, contrasting with the Church of the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, where light prevails.

The church’s broad bronze doors are adorned with a Byzantine-inspired grillwork depicting a dense thicket of plants, symbolizing the pre-Christian chaos of the world. This motif echoes the entrance of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, reinforcing themes of chaos and redemption. Over the doorway, an inscription echoes Jesus’ words to His disciples in Gethsemane: “Stay with me and spend the night here.” This invitation extends to all who enter, beckoning them to delve into the profound mystery of the Agony in the Garden that unfolded within this hallowed place.

The inauguration of the Church of Gethsemane, alongside the Mount Tabor church, took place in 1924, marking a significant moment in religious and architectural history. Constructed in a neo-classical style atop Roman foundations, the church is adorned with Byzantine-style mosaics. However, the essence of its art and architecture is distinctly unique, inspired by the conviction that churches built on the sacred sites of New Testament events should embody those narratives. This principle led to the creation of architectural designs that break free from conventional norms, resulting in a category of “visiting churches” found exclusively in Israel.

The church’s decoration was entrusted to a cadre of skilled artists, many of whom were Italian masters specifically recruited for this project. Among them were the artisans responsible for the mosaics in the gable (tympanum) at the church’s front and those who completed the mosaics in the apses in 1949. The allure of these mosaics alone makes the church a must-visit destination. Yet, the artistic marvels within extend beyond mosaics, encompassing a wide array of artworks that contribute to the church’s spiritual and aesthetic resonance.

The interior of the church is characterized by its spacious hall, which, despite being segmented by six slender columns, maintains an aura of expansive unity. Crowning this space are 12 modest, flat domes, each representing one of the 12 nations that participated in the First World War and subsequently united to construct the church as a symbol of reconciliation and peace. This inclusive dedication has earned it the name “the Church of All Nations,” embodying a testament to the possibility of harmony and cooperation beyond conflict. Flags of various nations, including France, Germany, the United States, Italy, and England, adorn each dome, serving as a reminder of their joint commitment to peace. Beneath these domes, the floor features mosaics—some of which are restorations from an earlier church on this site, weaving historical continuity into the fabric of the church.

On the eastern side, the church expands into three apses: a prominent central one flanked by two smaller ones. Directly in front of the central apse lies a natural rock, integral to the church’s foundation, believed to be where Jesus endured his agonizing vigil, sweating blood and water. This rock is encircled by what resembles a low barbed wire fence, evoking images of the brutal trench warfare of the First World War and perhaps symbolically echoing the crown of thorns. Within this poignant setting, two silver doves are depicted ensnared at the fence’s corners, while pairs of black doves seem to drink from a poisoned chalice, further deepening the church’s layers of symbolic meaning and historical reflection.

In the apse mosaic above the rock, created with Byzantine techniques yet infused with a style reminiscent of Van Gogh, Jesus is depicted leaning against the rock, with His disciples slumbering beneath a nearby tree. The entire scene is imbued with a sense of mourning: trees bow inward, the sky is speckled with clouds, and a sorrowful God gazes down, cradling His head. This combination of the rock, the emotive mosaic, the barbed wire-like fence, and the ensnared birds under dim lighting, vividly conveys the profound distress Jesus experienced during His Agony in the Garden. The atmosphere is heavy with the gloom of a dark night, suggesting an inescapable sense of despair enveloping everyone present.

Amid this somber tableau, however, there is a singular beacon of hope and salvation: the dome situated directly above the rock. This dome, distinct from the church’s other eleven, features a golden hue with a central blue circle held aloft by angels. Openings within the dome allow beams of sunlight and the twinkle of stars to penetrate the darkness below. This “spiritual sun” motif, a recurring element in Barluzzi’s work seen in Mount Tabor and his other churches, symbolizes a divine intervention, offering a glimmer of hope and guiding light amidst the shadows.

The Christian mystical tradition posits that beyond the tangible illumination of the physical sun lies a spiritual light, akin to a spiritual sun. Contrary to the physical sun’s depiction as a yellow circle against a blue sky, the spiritual sun is envisioned as a blue circle on a yellow background, symbolizing the inversion of realities between the spiritual and physical realms. This concept suggests that the dynamics of the spiritual world often stand in stark contrast to those of the physical world. For instance, in the material realm, giving away diminishes what one possesses, while in the spiritual domain, generosity enriches one’s spiritual bounty. Hence, the antidote to the dark night of the soul lies in the spiritual light, with a focus on the spiritual realm where order, significance, reward, and hope prevail over worldly chaos. The mysteries of life’s hardships remain elusive, rooted in a realm beyond our understanding, guiding us towards embracing all experiences with love as the answer lies in another world.

In the church’s left (north) apse, the narrative of Judas Iscariot betraying Jesus with a kiss is vividly portrayed, accompanied by soldiers wielding torches that cast ominous light, symbolizing impending doom. This scene captures the zenith of adversity at the most challenging moment, portraying a scenario where evil appears triumphant, leaving no apparent avenue for escape.

Conversely, the right (south) apse presents a path through this darkness: Jesus is portrayed radiating spiritual light, surrendering himself to the soldiers while inhibiting Peter from resistance. Here, the trees that once bent inward now reach outward, reflecting Jesus’s reconciliation and acceptance of his destiny with love, as the sky clears. The inscription beneath this mosaic, “Jesus saith unto them, I am he” (John 18:5), marks Jesus’s acknowledgment of his fate. When the disciples awaken post-ordeal, ready to defend, Jesus’s instruction to Peter, “Put up thy sword into the sheath: the cup which my Father hath given me, shall I not drink it?” (John 18:11), underscores the theme that understanding and accepting the enigmatic challenges of our world comes through love.

All nations Church

Mary’s tomb

The New Testament leaves Mary’s fate somewhat ambiguous, leading to the emergence of various traditions. One such tradition suggests that she moved to Ephesus with John, where she ultimately passed away and was assumed into heaven. Nonetheless, a more widely accepted belief is that she remained in Jerusalem, living among the early Christian community as depicted in the Acts of the Apostles. At the end of her earthly life, it is said that she “slept” on Mount Zion and was laid to rest in Miriam’s tomb within the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Miraculously, when the tomb was opened three days later to allow Thomas the doubter, who arrived late, to pay his respects, it was discovered empty; Mary had been assumed into heaven. This belief is underpinned by the notion that, having borne God in her womb, Mary’s body was divinized and taken to heaven alongside her soul. Thus, when her tomb was revealed to be vacant, it affirmed her heavenly assumption, a truth that persists to the present day (Dogma).

Following her interment, a celestial assembly comprising angels, prophets, and the heavenly hosts, led by Jesus, descended to escort Mary’s soul to paradise. In this moment, Mary’s soul, envisioned as an infant cradled by Jesus, presents a poignant inversion of the earthly image of Mary holding the infant Jesus. This spiritual tableau mirrors the physical relationship they once shared, symbolizing a divine reversal. As Mary’s life on earth concluded, her disciples and followers congregated to honor her, witnessing the divine procession led by Jesus to retrieve her soul. Overwhelmed by the sight, they offered prayers to Mary, imploring her to intercede on their behalf in the heavenly realm.

The Crusaders, recognizing the significance of Mary’s tomb, erected one of the kingdom’s most majestic churches around it. Queen Melisende commissioned the construction of a grand monastery and cathedral atop the site, which included a cave housing both Mary’s vacated tomb and Melisende’s final resting place. This sacred complex fell under the stewardship of the Templar order, transforming it into a pivotal center for Christian ritual and contemplation, dedicated to exploring the depths of the Christian mystery.

From the 12th century onward, Crusaders and pilgrims journeying to Israel introduced a renewed veneration and significance of Mary, significantly shaped by the teachings of Bernard of Clairvaux. Bernard, a pivotal figure of the 12th century, played a crucial role in founding the Templar Order, the Cistercian Order, and launching the Second Crusade, and is commemorated in Latrun. His influence post the Cluny reforms elevated the Virgin Mary to a prominent status within Christian devotion. By the 11th century, prayers dedicated to Mary began to be crafted, subsequently integrating into the liturgy. Among these were “Salve Regina” (Hail, Holy Queen) and “Alma Redemptoris Mater” (Loving Mother of the Redeemer), heralding the onset of Marian devotion. The 12th century saw the addition of two more liturgical hymns to this Marian repertoire: “Ave Regina Caelorum” (Hail, Queen of Heaven) and “Regina Caeli” (Queen of Heaven), further enriching the liturgical celebration of Mary’s role in Christian faith.

The proliferation of Mary’s worship, alongside other revered female figures like Mary Magdalene, during the 12th century is closely linked with the surge in pilgrimage activity, notably evident in the “Via Palma” in Israel. The inclusion of Marian sites along the pilgrimage routes imbued these journeys with additional sacredness and depth, making such locations pivotal to the pilgrims’ experience. Among these, Mary’s tomb in the Jehoshaphat Valley emerged as a key destination, enriching the spiritual landscape of the “Via Palma.”

Pilgrims traversing the “Via Palma” would immerse themselves in the profound narratives of Jesus’s trials, his moments of vulnerability, and the betrayal he faced, all of which unfolded amidst the ancient trees centuries earlier. In seeking solace and divine intervention, which seemed elusive during their meditative reflections on these events, they found comfort and hope at Mary’s tomb. It was here that pilgrims fervently sought Mary’s intercession, propelled by the belief that Jesus could not deny his mother’s requests. Armed with prayers like the Hail Mary and carrying images of Mary cradling the infant Jesus, they approached her tomb with faith in the power of her advocacy, confident that her petitions on their behalf would find favor.

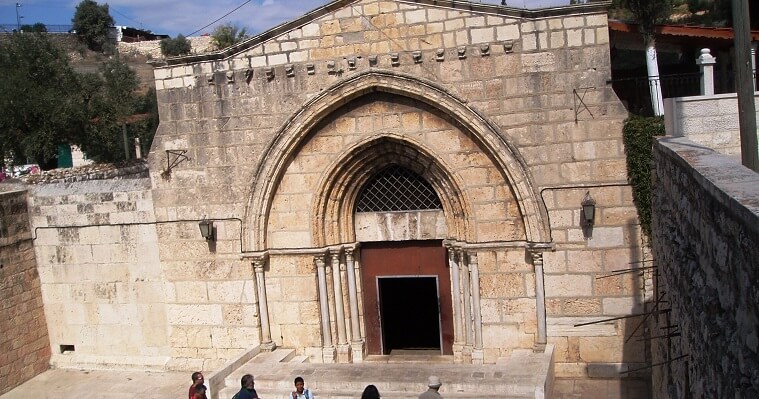

The Church of Mary’s Tomb, predominantly situated within a vast underground crypt, originates from a grand Crusader church constructed by Melisande, Queen of Jerusalem, in the 12th century, in partnership with the Templars. This era marked the Crusades as a time when the site served not only the Templars but also Benedictine monks affiliated with the Cluny reform movement. These monks adhered to the teachings of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who was also a guiding spiritual figure for the Templars, making this site a hub of intense spiritual engagement. Presently, the ownership of the building rests with the Greek Orthodox and Armenian churches.

The rise in Marian devotion is intricately linked to the Crusades, considered by some as a form of armed pilgrimage. It’s noteworthy that the day designated for embarking on a Crusade was chosen to coincide with the day of Mary’s Assumption into heaven, underlining her significance. Her image was prominently featured on the flag of the Pope’s envoy among the first crusaders. Mary’s tomb, the site of her Assumption, became a focal point of veneration immediately following Jerusalem’s capture by the Crusaders. Godefroy de Bouillon, one of the leaders of the First Crusade, erected a monastery on this site, possibly in appreciation of Mary’s perceived support. Later, in 1130, Queen Melisende, in collaboration with the Templar Knights, constructed a complex that included a magnificent church, underscoring its importance to her by choosing it as her final resting place.

Miriam’s tomb is situated at the lowest point in Jerusalem, nestled at the base of the Mount of Olives, the city’s highest eastern elevation. This arrangement likely mirrors ancient sacred geography where caves, embodying the earth’s womb, were revered as sanctuaries of the feminine divine, in contrast to the mountaintop’s association with male deities. Notably, Mary’s assumption to heaven took place from Jerusalem’s lowest point, juxtaposing Jesus’s ascent from its highest peak, each ascent distinct in nature and outcome.

Mary’s assumption is celebrated on August 15th, marked by grand processions originating from her birthplace at the Church of Santa Anna, situated within the old city’s walls near the Lions’ Gate, proceeding westward across the Jehoshaphat Valley to her tomb just outside the city walls. Additionally, the Gethsemane area hosts commemorative ceremonies. Adherents of the Orthodox tradition, who follow the Julian Calendar, observe Mary’s assumption on August 25th, with a procession that begins at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and culminates at Mary’s tomb, honoring her heavenly journey in a display of devotion and tradition.

Place of Ascension

The summit of the Mount of Olives stands as Jerusalem’s highest point, situated to the east of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Uniquely oriented towards the east, in contrast to other churches, this positioning ensures that the sunrise over the Mount of Olives, as viewed from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, daily reenacts the resurrection of Jesus. This natural phenomenon serves as a symbolic representation of Jesus, often likened to the Sun, illustrating the cosmic interplay of night and day that mirrors the Christian narrative of Jesus’s death and resurrection. Furthermore, the sun’s ascent over the Mount of Olives into the sky also signifies Jesus’s ascension to heaven from this very location, intertwining the celestial movements with the foundational events of Christian faith.

Christian tradition holds that Jesus ascended to heaven from the peak of the Mount of Olives, where a rock bearing his footprint marks this sacred event. Interestingly, Mary’s tomb is situated at Jerusalem’s lowest point, within the depths of the Kidron Valley (also known as the Valley of Jehoshaphat), just east of the Temple Mount. Yet, further east, the Mount of Olives rises as the city’s highest elevation. This geographic contrast poignantly illustrates that Mary’s ascent to heaven originated from the lowest locale, whereas Jesus ascended from the highest. The English language captures this distinction through specific terms: Jesus’s departure is referred to as the Ascension, while Mary’s is known as the Assumption. Pilgrimages to these sacred sites—representing the Ascension of Jesus and the Assumption of Mary—are integral to Christian faith, reflecting a deep-seated belief in the Mount of Olives as the location from where Jesus will return and initiate the resurrection. This act of visiting both sites not only honors these pivotal moments but also resonates with the anticipation of Jesus’s second coming, viewing the Ascension and Assumption as harbingers of this future event.

The rock imprinted with Jesus’ footprint is one among three sacred rocks that together delineate Jerusalem’s “Messianic line” or spiritual ley line. This trio includes the Golgotha Rock and the Foundation Rock situated on the Temple Mount. These sites are interconnected: the Jewish Temple, constructed atop the Foundation Rock, was oriented eastward, facing the Mount of Olives’ summit. Similarly, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built over Golgotha, features an entrance facing east towards the Mount of Olives, diverging from the traditional westward orientation of other churches. This precise alignment of the three rocks along an east-west axis, with the Mount of Olives’ peak as the focal point, underscores a profound spiritual and historical connection among these significant locations.

In the 4th century, a significant Byzantine church was erected at this location, only to be demolished by the Persians in the 7th century AD. Upon their arrival in Jerusalem, the Crusaders constructed a large octagonal church, at its heart an open-to-the-sky Aedicule surrounded by slender columns, adorned with special capitals featuring griffons—mythical creatures part lion, part eagle. These griffons symbolized Jesus’ ascension to heaven and the dimensional transition it entailed (from the element of fire, represented by the lion, to air, symbolized by the eagle). Following Jerusalem’s capture by Saladin, the church was destroyed, and the site transitioned into Muslim hands. During the Ottoman period, a mosque was established nearby, with the ascension site and its rock sheltered by a small original cupola becoming part of the mosque’s courtyard. Presently, this area forms a spacious courtyard encircled by walls, primarily visited by Christian pilgrims. The courtyard’s centerpiece is the small cupola sheltering the sacred rock.

Adjacent to the Ascension site, the Pater Noster Church and convent house an ancient cave, celebrated for its connection to the foundational Christian prayer, “Our Father in Heaven.” This site is commemorated for Jesus’s teaching of this prayer to His disciples, a moment alluded to in Acts 1:3, which describes Jesus appearing to His followers over forty days, offering them teachings on the kingdom of God. The cave served as the final resting place for several Byzantine Patriarchs of Jerusalem, figures familiar to many pilgrims. Over this sacred cave, the Byzantines erected the grand Eleona Church, later restored by the Crusaders.

Pilgrims visiting were often struck by the breathtaking vistas of Jerusalem from the mountain’s peak, with views extending to the Judean desert and Transjordan on the opposite side. The mountain, dotted with monks’ caves and cells, offered a spiritual journey through its holy sites and churches. Visitors would venerate the Rock of Ascension and possibly time their visits to coincide with the poignant moments of sunrise or sunset. Within the hallowed confines of the ancient cave, pilgrims devoutly recited the Lord’s Prayer, echoing the words taught by Jesus: “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. For Thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory forever. Amen” (Matthew 6:9-13).

The Church of Our Father in Heaven, established at the close of the 19th century, occupies the historic site of the Byzantine Eleona Church. At the church’s entrance, visitors are greeted by the tombstone of a reclining woman, representing the French princess Aurelia de Bussy. In 1866, she journeyed to Israel, acquiring the church’s ruins, remnants from the Crusader period. By 1875, she had overseen the construction of the present building, subsequently entrusting it to Sister Xavier, a Carmelite nun from France, for the Carmelite nuns’ use. Presently, the monastery is home to 17 Carmelite nuns. The monastery’s courtyard now features the “Our Father” prayer showcased in over 160 languages, each rendered on elegantly designed ceramic tiles, reflecting the global reverence for this foundational Christian prayer.

Gnostic mystical traditions suggest that Jesus imparted more than just the prayer and its significance; He also introduced the disciples to the deeper Christian mysteries on the Mount of Olives, possibly within this cave or another. Caves, symbolizing introspection and depth, serve as apt metaphors for such spiritual initiation. The Ascension Mystery, in particular, illuminates the anticipated future event of the resurrection of the dead, when humanity is believed to return to a spiritual state, residing in heaven and savoring the delights of the spiritual realm. This prospect offers hope, yet it necessitates individual growth and transformation. Achieving this vision involves ascending the spiritual ladder, an endeavor metaphorically represented by the rosary. The summit of the Mount of Olives, with its sites of the Ascension and the nearby Our Father in Heaven church, presents a prime location for contemplation on the Ascension Mystery, inviting reflection on spiritual elevation and the promise of eternal bliss.