Generators of Sacredness in the Wailing Wall

A considerable amount of literature has been devoted to the Wailing Wall, encompassing historical, political, and religious perspectives, as well as to a lesser degree, the architectural aspects of the newly constructed Wailing Wall plaza and the various traditions it embodies. Following the liberation of Jerusalem in 1967 and the subsequent development of the Wailing Wall plaza, the site has acquired additional layers of meaning, both national and religious. Furthermore, visits to the Wall have assumed cultural, folkloristic, and personal dimensions. I contend that, in certain cases, dependent upon the individual, the purpose, and the process of the visit, there exists an additional dimension: the desire for a religious experience at this location.

The increasing development and popularity of visits to the Wailing Wall, which mirrors the trend observed in the visits to the tombs of certain Zadikim, are also influenced by this dimension. In both instances, the purpose of the visit is to experience the sacred, a phenomenon that is augmented by what I refer to as ‘Sacredness Generators.’ These are elements inherent in the architecture, layout, characteristics, and ethos of the site that contribute to its sacred atmosphere.

The capacity of the Kotel to evoke religious experiences is evidenced by the fact that it is not only Jews who feel the sacredness of the place, but also others, particularly those who visit independently[1]. It is not merely the wall itself, but the comprehensive arrangement of the plaza and its interaction with the surrounding environment that contributes to this phenomenon. The widespread popularity of the site is captured in numerous photographs, suggesting that its appeal is not solely historical or political, but also relates to its unique physical attributes. Moreover, the experience of visiting the Wailing Wall can facilitate a transformative process in individuals, akin to a hero’s journey, leading them through significant personal change or conversion.

The experiences of visitors at the Wailing Wall are not uniform; they are influenced by subjective factors such as cultural background and objective factors related to personality structure. The likelihood of undergoing a religious experience at the site also hinges on the visitor’s preparatory measures and mental state, the journey they undertake, but significantly on the interactions they have within the place—the external environment impacts the internal psyche. The foundational argument of this article posits a profound connection between an individual and a place, which resonates on multiple levels, serving as a wellspring of self-identity and eliciting a range of emotions and feelings. Encountering a place is akin to encountering another person, necessitating an interaction that predominantly occurs on an unconscious level, beneath the surface. The aim of this paper is to elevate this interaction to the level of consciousness, elucidating the processes and outcomes associated with visiting sacred, charismatic locations and the ensuing religious or mystical experiences.

The psychic connection between an individual and a location can often be understood through the lens of memories. When prompted to recall our earliest or most significant memories, they are frequently tied to a specific place, or sometimes to a physical sensation within the body. This phenomenon underscores the universal experience of returning to a familiar environment—such as home—and the diverse array of emotions and sensations it evokes, often referred to as affect. Similarly, the contrasting feelings elicited by entering a “welcoming” hotel room versus one that “doesn’t seem right” further illustrate this intricate relationship. These experiences highlight how our perceptions and emotional responses to places are deeply interwoven with our sense of self and our memories.

Just as ordinary feelings and emotions are evoked in association with a place, so too is the sensation of sacredness in certain locales, which for the purposes of this article, we will refer to as “charismatic” sacred places. Many individuals report feeling a divine presence in nature, yet not every natural setting evokes the same response; some locations trigger profound feelings while others do not. For example, the experience atop a desert cliff at sunrise significantly differs from the sensation felt on a desert plateau at midday. Similarly, certain built environments inspire awe and wonder, whereas others fail to evoke such reactions. When engaging with nature, we tend to imbue it with life, leading to the association of specific places and objects, such as trees or rocks, with spiritual entities. In the field of religious studies, the manifestation of the sacred in physical locations and objects has been termed hierophany by Mircea Eliade. This paper aims to identify and discuss the general characteristics (generators) of a place that facilitate such occurrences.

To thoroughly explore this topic, it is imperative to first define what constitutes the Sacred and what does not, as contemporary interpretations of this concept can be vague, and not everything deemed Sacred truly embodies this quality. Drawing upon the insights of eminent scholars in the field of comparative religious studies—such as William James, Rudolf Otto, and Mircea Eliade—the Sacred is associated with profound emotions and feelings, including gratitude and awe. It involves the recognition of being part of something greater, powerful, and awe-inspiring, coupled with the understanding that this formidable power is benevolent and the source of joy.

Rudolf Otto endeavored to define the characteristics of the numinous experience, or the encounter with the Sacred. According to his analysis, when in contact with the Sacred, an individual may experience a spectrum of feelings distinct from the ordinary, including: the sensation of being created, accompanied by a sense of humility (creational feeling); the Mysterium Tremendum, which evokes a profound awe and mystery; Majestas, the recognition of an overwhelming majesty; Deinos, indicating the daunting or fearsome aspect; Fascinans, the allure or captivating quality of the sacred; and Augustum, suggesting a revered or exalted state. Otto posits that the experience of the Sacred is akin to a heightened form of religious emotion, akin to those described by individuals who have attained enlightenment or union with the divine, where duality merges, opposites unite, and the transpersonal aspects of an individual are engaged. In such a state, one’s perception, consciousness of time, thought processes, emotional responses, and even physical condition undergo transformation. This article asserts that certain elements within the structure and layout of the Wailing Wall plaza facilitate the induction of the Sacred experience and can be engaged during a visit by those who are predisposed to such encounters.

The phrase “those who are predisposed to such encounters” refers to the idea that not every individual will have the same depth of experience or reaction in the presence of what is considered sacred or sublime, similar to the varying responses people have when exposed to masterpieces of art. For instance, while many may view the paintings of Van Gogh or the sculptures of Raphael, not everyone will undergo a profound aesthetic experience. This suggests that while art transcends mere subjectivity and resonates with universal archetypes of perception, the capacity to fully engage with and appreciate a work like the Mona Lisa hinges on the individual’s personality structure, cultural background, previous exposure to art, and the cumulative experience and education in art perception accumulated over their lifetime. Despite these individual differences, certain aspects of beauty are universally recognized and can evoke similar responses across diverse audiences.

Just as there are certain universal principles of beauty—such as proportions, compositions, and combinations—that are innately perceived as beautiful by humans, similarly, standing on a desert cliff at sunrise can offer anyone a profound experience of nature, potentially leading to what is known as a peak experience. The transformation of light, the softness and refinement of colors, the gradual unveiling of the landscape, and the striking appearance of the red sun, distinct from the ordinary, all contribute to a heightened sense of the sacredness of time and place, transcending individual differences. Naturally, if one is preoccupied with their cellular phone, this connection to the environment can be significantly diminished, regardless of their location. However, generally speaking, the human experience of beauty and awe in the presence of certain natural phenomena remains a shared experience, supported by the natural conditions described.

Moreover, certain practices can amplify the experience of a special place and time, such as maintaining silence and adopting a posture of stillness with focused concentration during the sunrise, or ascending a high mountain in the predawn darkness with the intention of witnessing the sunrise. This balance of focus and intention on one side, and openness and surrender on the other, is crucial. The same principles apply to visiting sacred sites. For instance, experiencing the Wailing Wall at sunrise, when the plaza is less crowded, the colors are soft and delicate, the surrounding sights gradually come into view, and dawn prayers begin, can profoundly affect us differently than visiting during midday under the harsh sun, amidst the bustling crowds of a Bar Mitzvah, when noise and commotion hinder any possibility of a personal, internal process.

Even in the absence of ideal conditions, provided there are no significant obstacles to a genuine experience during a visit, the “Sacredness generators” will become active in the interaction between the visitor and the site. These generators exist potentially within the complex’s patterns, its structure, art, layout, and composition before the visit. During the visit, they are animated within the perceptions of visitors who are receptive to mystical experiences, initiating, fueling, and encapsulating these experiences. The external structures resonate with archetypes within the visitor’s perception, altering it and facilitating an encounter with the Sacred. This interaction underscores the dynamic relationship between the physical environment of a sacred site and the internal receptivity of the visitor, enabling a profound experience of the Sacred.

This experience, whether subtle or profound, which may often remain at the unconscious level, is what imbues specific sacred places with their charismatic allure. The presence of these “Sacredness generators” is a primary reason such locations gain popularity and capture our imagination, drawing us to them in the same instinctual manner we are drawn to a beautiful person. The essence of the phenomenon lies in the transformation that occurs upon entering the sacred space: the presence of these generators alters our perception, crafting a new, sublime, and transcendental image of the place in our minds. This reconstructed perception, powerful and compelling, imposes itself upon us, triggering an experience that is typically unexpected and beyond rational explanation. The encounter with the sacred thus transcends ordinary perception, inviting a deeper, often ineffable, experience that resonates deeply within the individual.

Although the characteristics—or “generators”—of sacredness in sacred places might vary across cultures, at their essence, they are objective rather than subjective. This objectivity is rooted in our way of perceiving reality through the higher, transpersonal parts of the human psyche. This claim can be substantiated using the phenomenology of religious sciences, as Mircea Eliade elaborates in his seminal work “Patterns in Comparative Religion”[2]. Nonetheless, one should not rely exclusively on this source. Evidence supporting the existence of these sacredness generators can also be found in other academic domains, including environmental psychology, transpersonal psychology, the psychology of religion, and even the critique of aesthetics and art. These interdisciplinary insights collectively affirm the objective foundation of sacredness in certain locations, beyond the subjective interpretations influenced by cultural lenses.

In the subsequent sections, we will delve into the Sacredness generators present within the Wailing Wall complex, focusing on the context of a personal and undisturbed visit. This entails an exploration that provides ample time, space, and openness for the visitor to undergo a transformative process of change and absorption. Our analysis will commence with a brief historical overview of the site, highlighting aspects pertinent to our study. Following this, we will introduce and discuss the existence and function of the four primary Sacredness generators: the Sublime Unusual, Unifying Duality, Connecting Center, and Fractal Complexity. Through specific examples from the Wailing Wall, we aim to enhance our comprehension of how these generators operate, not only within this particular sacred site but also in understanding their broader application and impact in sacred spaces.

History of the Wailing Wall

Numerous traditions and legends are associated with the Wailing Wall, such as the belief that “Shekinah never departed from the Western Wall of the Temple” (Bamidbar Rabbah, 11, 2). However, many of these are anachronistic and pertain specifically to the Western Wall of the Temple structure itself. The veneration of the Wailing Wall, which constitutes part of the retaining walls surrounding the Temple Mount and is distinct from the Temple edifice, emerged relatively late in history. While early traditions might have referenced this section of the retaining wall due to its proximity to the Holy of Holies, its significance only began to amplify during the Mamluk period[3]. Individual prayers at this site commenced in the 17th century, with the first public prayer recorded in 1650[4]. The transformation of the Wailing Wall into a pivotal religious site correlates with the development of the Jewish quarter in the sixteenth century, acquiring further depth and significance throughout the twentieth century. The prominence of the Wailing Wall has also evolved in tandem with the progression of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

In the Ottoman period, the Wailing Wall served as a locus for the religious mourning of Jews over the destruction of the Temple, coupled with prayers for its prophesied divine restoration and redemption, as it was believed the Temple would descend from heaven fully constructed. The practice of mourning involved tears and supplications, giving rise to the appellation “Wall of Tears.” It was during this time that the custom of placing written requests between the stones of the wall emerged, further cementing the Wailing Wall’s role as a tangible interface between the devout and the divine.

The “miracle” of the Six-Day War and the iconic images of soldiers and public figures praying at the Wailing Wall ignited a wave of messianic fervor, leading to the demolition of the Moghrabi Quarter adjacent to the Wailing Wall and the establishment of the contemporary plaza. This development effectively created a distinct space, delineating it from the residential areas of the Jewish and Muslim quarters, thereby amplifying the site’s sanctity[5]. The reclaiming of the Wailing Wall was heralded as a pinnacle in the journey towards national independence, prompting even secular Israelis to regard the wall as a symbol of national identity, and drawing them to visit it frequently. The tradition of placing notes with personal petitions between the wall’s stones gained momentum, paralleled by the initiation of bar mitzvah ceremonies at the plaza on Mondays and Thursdays—days associated with Torah readings[6]. Furthermore, the plaza emerged as a venue for significant national events, including soldiers’ swearing-in ceremonies, underscoring its role as a focal point of religious, national, and spiritual inspiration[7].

My contention is that the development of the site has come to symbolize, for many, the return of the Jewish people to Jerusalem after centuries of exile. In recent years, the Wailing Wall has seen a surge in popularity among traditional and national religious communities, increasingly representing the essence of the Temple in Jerusalem. The demolition of the adjacent houses and the establishment of a spacious plaza in front of the Wailing Wall have crafted a sacred expanse that is sufficiently large to be remarkable and sufficiently delineated to be distinct—sanctified from the secular, with security checks at the entrance further marking the transition from the external to the sacred internal. The site’s expansion and complexity have transformed it into a “World of its own,” facilitating an “Imagio Mundi” (World Image). The focalization on the wall within this newly formed structure has elevated it to an Axis Mundi, a symbolic center of the world. The integration of the plaza with the wall, along with the reflection of the wall in the plaza’s stone pavement, accentuates both horizontal and vertical dimensions. Collectively, these elements have created an environment conducive for the Wailing Wall site to evolve into a charismatic and impactful presence for its visitors. The deliberate and incidental incorporation of Sacredness Generators within this reimagined structure has imbued the site with a dynamic and potent sacredness.

While the Wailing Wall carries significant historical and religious weight, serving as a reminder of the Temple and a national emblem, the roots of its popularity extend beyond these factors. The unveiling of the Wall, the construction of the Plaza, and the meticulous arrangement of the site have led to the incorporation of four Sacredness Generators, namely: the Sublime Extraordinary, Unifying Duality, Connecting Center, and Fractal Complexity. The essence and impact of these generators will be explored in detail, shedding light on how they contribute to the site’s profound influence and attraction for visitors. These elements not only enhance the physical and aesthetic appeal of the Wailing Wall but also deepen its spiritual and symbolic significance, drawing individuals into a closer engagement with the sacred.

Sacredness Generator Sublime extraordinary in the Wailing Wall

The Sacredness Generator termed the Sublime Extraordinary is capable of manifesting through attributes that are remarkable in size, volume, height, or beauty—any extraordinary physical characteristic that draws our attention to the site we are visiting, prompting a shift in our perception from the mundane to the sacred. The encounter with something unusual sharpens our focus and enhances the sensitivity of our perception. This heightened awareness activates our senses, leading us to perceive the environment in a way that differs from our previous encounters. Within this new state of awareness, the Sacredness Generators begin their operation, where the presence of certain external archetypes triggers the activation of corresponding archetypes within us. This encounter with the extraordinary ushers in the numinous experience, potentially evoking feelings of fear and surprise, which in turn can give rise to wonder and awe. Through this process, the extraordinary aspect of the environment acts as a catalyst, transforming our ordinary experience into one that is deeply connected with the sacred.

A pivotal aspect of the Wailing Wall’s profound impact on its visitors, contributing to its charisma and capacity to facilitate inner religious experiences, is, from my perspective, derived from the extraordinary dimensions of its stones, the expansive size of the Plaza, and the imposing height of the Wall itself. The deliberate architectural decision to lower the Plaza towards the Wall places visitors at its base, thereby magnifying the Wall’s stature and the monumental scale of its stones, engendering a sense of sacredness. This design choice, as articulated by architect Yosef Schenberger, was intentional: “By lowering the area adjacent to the Wall, he aimed to amplify the Wall’s presence and dominance over its immediate environment.”[8] This strategic manipulation of spatial dynamics not only enhances the physical impression of the Wall but also deepens the spiritual and emotional engagement of those who come to witness it, reinforcing the Wall’s symbolic potency.

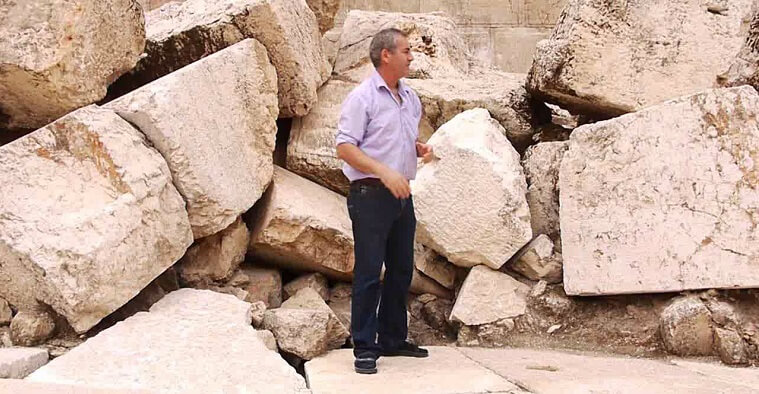

In the course of redeveloping the Wailing Wall site, significant modifications were made to enhance its sacred character. The prayer area was excavated further into the ground, revealing two additional layers of the wall’s massive stones, thereby extending its height to nineteen meters. Furthermore, a large and distinctively segmented plaza was constructed, leading up to the wall, surrounded by several buildings and spaces. This redevelopment introduced three Sacredness Generators into the site: Unifying Duality, Fractal Complexity, and the Connecting Center. The Sacredness Generator of the Sublime Extraordinary was already inherent to the site due to the immense size of the stones; however, this feature was further accentuated throughout the construction process. These architectural and spatial enhancements not only underscored the physical grandeur of the Wall but also deepened its spiritual ambiance, reinforcing the site’s capacity to engender a profound sense of the sacred among its visitors.

The remarkable size of the stones is often the most striking feature for visitors at the Wailing Wall, capturing their attention, becoming a focal point for photographs, and, in my perspective, playing a central role in sanctifying the site for people beyond just the Jewish community. It transcends the historical significance, the two thousand years of diaspora, and the religious, national, and historical relevance of the place. My argument posits that a significant portion of the wall’s allure is derived from the extraordinary dimensions of its stones. Had the Wailing Wall been constructed with stones of a “normal” size, it likely would not have elicited the same profound impact. This unique characteristic is further amplified by the tradition of inserting notes between the stones, marking a pinnacle in the visitor’s experience and the personal journey undertaken during their visit. The stones become more than mere structural elements; they are interacted with—touched, caressed, spoken to, leaned upon, and cried over—imbuing them with life and thereby facilitating a hierophany, transforming them into “stones with a human heart” (Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, “Machher Kotelno”, 1939). The extraordinary scale of the stones enhances this intimate dialogue between the visitor and the sacred, contributing to the Wall’s unique spiritual resonance.

A significant aspect of the Wailing Wall’s influence on visitors is attributed to its towering height and the substantial size of its stones, which exude a sense of power. The plaza’s design, sloping towards the Wall, positions the visitor before an extraordinary structure that is perceived as a portal to a different realm[9]. This physical impasse, marked by its remarkable characteristics, prompts a shift towards a spiritual dimension. Mircea Eliade posits that a stone can become a conduit for hierophany, a manifestation of the sacred[10]. In the context of the Wailing Wall, the extraordinary size of its stones plays a crucial role in facilitating this spiritual phenomenon, but the impact is not solely due to their size. The stones acquire a “sublimity” that is intertwined with the historical depth of the site and its connection to the Temple, thereby acting as a Sacredness Generator of the Sublime Extraordinary. Eliade suggests that a stone epitomizes the eternal, making it a potential symbol of divine presence or power. However, as Rani elucidates, not every stone achieves the status of a hierophany: “And thus a stone, which is merely a stone, is transformed by the observer into a vessel of energetic presence and sanctity.”[11]. This transformation underscores the interplay between the physical attributes of the stones and the collective consciousness and historical memory of the observers, imbuing the stones with a profound sense of sacredness beyond their material existence.

The stones of the Wailing Wall hold deep and widespread sacred significance for all Jewish people, and they also resonate with other visitors to the site. My argument contends that the charisma of these stones, and thereby the capacity of the Wailing Wall to catalyze an inner religious experience of sanctity, is derived in part from their extraordinary dimensions. The size of the stones, along with the wall and the plaza, captivates attention and intimates the presence of another realm governed by laws distinct from those of our mundane world. This suggestion of an alternate reality, marked by the stones’ imposing presence, plays a pivotal role in the spiritual and emotional impact of the Wailing Wall, prompting visitors to contemplate and engage with the sacred.

Sacredness Generator Unifying duality in the Wailing Wall

When we begin to perceive our surroundings in a new light, they seem to acquire human-like qualities, exerting both emotional and physical effects on us. The environment becomes animated, imbued with life—though these qualities are often subtle and concealed. It engages us through invitation, suggestion, revelation, and communication, transforming into a mirror for our internal processes and consequently shaping them. For instance, the rising sun not only symbolizes joy but can also elicit feelings of happiness, while darkening clouds might symbolize gloom and provoke fear. This dynamic interaction between our perception of the environment and our internal emotional state underscores the profound impact our surroundings can have on us, acting as a catalyst for emotional and psychological experiences.

Our engagement with the environment is far from neutral; as we familiarize ourselves with a place, we imbue it with layers of mental, emotional, and even physical significance. In the context of a sacred site, this interpretive process draws us closer to the sublime and the numinous. This connection is facilitated by the presence of duality within the sacred space—a duality that may be contrasting yet interconnected, offering either a complementary or amplifying relationship between opposing elements. These manifestations of duality, such as the interplay between the horizontal and vertical dimensions or the juxtaposition of heaven and earth, mirror the internal dichotomy within us: the physical aspect tethered to the mundane and the spiritual (or mental) realm linked to the sacred and eternal. The activation of the Sacredness Generator of Unifying Duality cultivates a sense of interconnectedness among all things, fostering a profound unity between the different parts of ourselves, ourselves and the place.

Transitioning from an examination of the individual stones to the broader architecture of the Wailing Wall compound reveals another aspect of the Sacredness Generator Unifying Duality at work within the layout of the Wailing Wall Plaza and its relationship to the Wall itself, manifested in the interplay between the horizontal and vertical vectors of the site. This aspect, while not immediately apparent, significantly contributes to the Wall’s charisma. A subtle yet profound connection exists between the wall and the plaza’s flooring, established unintentionally but effectively influencing visitors on an unconscious level. This interconnection, bridging the divide between the earthbound (horizontal) and the transcendent (vertical), enriches the sacred ambiance of the place, engaging visitors in a deep, albeit often subconscious, dialogue with the space.

Initially, the convergence of the horizontal and vertical vectors (the wall and the plaza flooring) represents a transition from the physical journey to the spiritual quest, facilitated by prayer on-site. Approaching the towering and majestic wall, which entails a descent, and positioning oneself beside and beneath it, integrates these horizontal and vertical dimensions. The vertical dimension is perceived as a conduit to the divine, further enhanced by the historical presence of the Jewish Temple beyond the wall. The site’s architects, Yosef Schenberger and Shlomo Aharonson, intentionally designed the pathway leading to the wall, aiming to impact the visitors’ experience profoundly[12].

Another evident duality emerges from the visible space of the Plaza juxtaposed with the invisible aspects symbolized by the wall and its concealed elements. In numerous sacred architectural practices, the concept of a hidden portal holds greater significance than an overt entrance. This principle is manifested in designs such as the sealed or obscured windows found in Barluzzi’s churches on Mount Tabor and Mount of Beatitudes, or through the veiling of the sanctuary within the Temple, the symbolic false doors for spirits in ancient Egyptian tombs, among others. The significance of the Wailing Wall stems from what lies beyond its visible structure, specifically, the hidden site of the Temple Holy of Holies, and the foundation rock of the world. Thus, the physically sealed wall represents a spiritual gateway. The act of inserting notes with prayers and requests into the wall’s crevices serves to metaphorically ‘open’ this spiritual portal.

My interpretation suggests that the Wailing Wall is subconsciously regarded by visitors as a portal to an alternate reality, which is why it becomes the focal point for their requests, supplications, and prayers. The act of turning towards the wall, standing before it, fundamentally alters the impact of prayer. The physical act of positioning oneself in front of a distinct medium—namely, a towering wall adorned with massive stones—deepens and amplifies the experience of being in the space, potentially catalyzing an inner religious awakening. This phenomenon may also relate to a deep-seated archetype within our subconscious, akin to confronting an impassable rock cliff in nature, at which point humanity finds itself at the mercy of a greater force.

Additionally, there’s an element of the Wailing Wall that might not be immediately apparent but is perceived on an unconscious level. As the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus (circa 500 BC) posited, nature tends to conceal its wonders, among which are specific proportions like the golden ratio, also known as the divine proportion[13]. It’s therefore intriguing to note that the dimensions of the Wailing Wall align with the golden ratio. This proportion is observed between the upper, Ottoman part of the wall, constructed with smaller stones and measuring five meters in height, and the lower, Herodian section, comprised of massive stones and standing approximately thirteen meters tall. The figures five and thirteen are integral to the Fibonacci sequence, which is the mathematical representation of the golden ratio.

Two proportional relationships exert a profound effect on humans, as they represent archetypes within our aesthetic perception. One such relationship is the golden ratio, revered for its dynamic and beautiful qualities[14], while the other is the two-thirds and one-third ratio, esteemed for its harmony. The ratio between the height of the entire Wailing Wall, nearly nineteen meters, and its width, exceeding fifty-six meters, adheres to the two-thirds and one-third ratio—a harmonious proportion. Furthermore, as demonstrated earlier, the presence of the golden ratio, albeit unconsciously perceived, further enhances the wall’s dimensions. The incorporation of these two ratios in the wall’s dimensions serves to evoke a sense of holiness among visitors to the site, with the golden ratio forging a connection between the wall, the visitor, and the Plaza.

In Platonic geometry, the union of two elements necessitates a mediator, a role fulfilled by the geometry and proportions of the golden ratio[15]. According to this perspective, fire and earth, two fundamental elements composing our world, require the golden ratio to bridge them. While fire instigates growth and development within the earth, the path of its expansion, occurring through the earth, aligns with the golden ratio. Fire embodies movement, while earth embodies stability, and the proportion of the golden ratio serves as the intermediary between them. Thus, on an unconscious level, the presence of this proportion in the Wailing Wall establishes a connection between the vertical wall and the horizontal square.

However, discussions with the site’s researcher, Dr. Shmuel Bhatt, suggest that there may have been no deliberate intention to adhere to these specific proportions in the exposure of the Wall[16]. The decision to lower the extension (thus raising the Wall) was driven by a desire to enhance the sense of awe and reverence (a Religious emotion) associated with the site. Additionally, the lowering of the extension was conceived with the idea that the descent towards the wall would symbolize a preparatory step for spiritual ascent—a physical descent indicating the necessity for humility in the presence of the divine[17]. In essence, there was a conscious intention for the Wailing Wall to serve as a transitional space where individuals would traverse between horizontal and vertical planes. However, there was no conscious consideration of the golden ratio, and any apparent alignment with it was likely coincidental or attributed to divine intervention.

In my interpretation, the focal point around which the site is organized is the wall itself. The central principle shaping the space is the act of prayer and supplication in front of a wall symbolizing the Temple. The visit to the site revolves around this central motive, with the mana of the Temple transferred to the Kotel as a conduit to the Divine. Just as the Temple served as a locus where prayers were communicated and answered, serving as a nexus between God and the people of Israel, similarly, the Wall is perceived as a medium through which prayers are conveyed and received[18]. The Wailing Wall thus stands as a link between God and Israel, bridging the Sacred and the Divine.

In addition to the unifying duality inherent in the Kotel, there’s also an observable presence of separating duality. Konin suggests we’re witnessing the inception of a new phenomenology regarding the manifestation of holiness in Israel, characterized by an accentuation of Jewish nationalism and a juxtaposition with the nations of the world[19]. This contrast is evident in the juxtaposition of the Wailing Wall plaza with the Dome of the Rock and the plaza of the Temple Mount situated above it. However, interpretations may vary, and some observers may perceive a profound connection between the two religions and their respective Sacred places.

Sacredness Generator Connecting Center in the Wailing Wall

The Sacredness Generator Connecting Center is reminiscent of Eliade’s concept of the Axis Mundi and Imagio Mundi. According to Eliade, every human dwelling and Temple serves as a microcosm, housing a center where the world is perpetually recreated. This center serves as a nexus connecting different physical realms (underworld, earth, and sky) and different planes of existence (Sacred and profane), often symbolized by archetypes such as mountains, trees, columns, or rocks. I would further argue, as elucidated elsewhere, that the center need not necessarily be physical; it can also manifest as an orientation or narrative.

Undoubtedly, the center acts as a focal point where creation undergoes perpetual renewal, serving as a hub of human activity. From ancient times, it may have been symbolized by the fire within a cave, evolving into the pole within a hut as settled structures emerged. This highlights the notion that the center serves as a conduit through which the Sacred manifests within the profane—a site of Hierophany where the axis of the world connects different planes of existence. Hence, I chose to incorporate the term “connecting” into its definition, emphasizing that it signifies not merely a physical center but rather a point of connection to the Sacred.

Indeed, the foundation rock within the Jewish Temple epitomizes the concept of a connecting center. It is revered as the site where the world was initially created and where this act of creation perpetually unfolds, bridging the realms of existence—the Sacred and the profane. The Wailing Wall, symbolizing the Temple, assumes paramount significance as the most Sacred site for Jews and a revered destination for pilgrimage. Positioned closest to the Holy of Holies, housing the foundation rock, it serves as a focal point for Jewish prayers worldwide, directing their devotion towards the sacred site of the Temple in Jerusalem, now symbolized by the Wailing Wall.

Noga Collins-Kreiner delineates the Wailing Wall as an established locus and a focal point for continuous acts of prayer, vows, and the depositing of notes. Rituals are conducted with formality, segregating men from women, and adhering to modest attire and head coverings [20]. She contends that unlike many popular pilgrimage destinations, the Wailing Wall lacks folkloric activities such as feasting, music, or expressions of joy. Notably absent are the customary distribution of sweets, the lighting of candles or torches, as well as commercial enterprises, stalls, itinerant vendors, mendicants, blessing bestowers, or supplicants within or proximate to the Wailing Wall precinct. Consequently, while the site does not conform to Turner’s concept of ‘liminality,’ it occupies a central position culturally, politically, geographically, and socially [21].

Contrary to Noga Collins-Kreiner’s depiction, the Kotel does indeed include certain folkloristic elements, notably evident during Bar Mitzvah celebrations. For many, the journey to this site represents a liminal experience, symbolizing transition and personal growth. While Collins-Kreiner emphasizes its symbolic national significance, the center I refer to acknowledges both its physical and spiritual dimensions. Physically, it encompasses numerous focal points dispersed along the entirety of the wall. Spiritually, its importance stems from the profound connection between the wall and the foundational bedrock of the Temple.

Sacredness Generator Fractal Complexity in the Wailing Wall

Once a connection is established between the planes, and the stones in the Wall transcend mere physicality to become Heirophanies, the entire environment undergoes a perceptual shift. Reality itself transforms as our perception, shaped by this connection, reorders and recreates the world around us. This is where the Sacredness Generator Fractal Complexity comes into play, aiding us in constructing our new worldview, the Imagio Mundi, based on inherent archetypes of holiness within us. For instance, a square oriented towards the four directions represents such an archetype, as does a division into three parts nested within each other. The four-fold orientation correlates with our spatial perception, delineating the world into forward, backward, right, and left, while the tripartite division mirrors our cognitive processes of conscious, semi-conscious, and subconscious, or the temporal flow between past, present, and future. These archetypes within us resonate with cosmic arrangements in the external world; for example, the tripartite division reflects the arrangement of the sun, earth, and moon, or the dimensions of space. Similarly, the square archetype mirrors the four states of matter (solid, liquid, gas, and plasma). Jung emphasized the pivotal role of these archetypes in shaping our perception [22].

The new world we construct in our minds mirrors the essence of the Sacred; we project our archetypes onto our surroundings, shaping our perceptions of what we encounter. If a place possesses the appropriate “anchors,” it can manifest in the image we desire to perceive. As Goethe once remarked, we tend to see what we seek, a principle echoed in gestalt theory. For instance, the concept of holiness in Judaism posits a nesting of entities within each other (Mishnah, Kelim 1, 69), illustrating ten degrees of sanctity ranging from the borders of the Land of Israel to the Holy of Holies in the Temple. This concept finds contemporary expression in the layout of Jerusalem and the positioning of the Wailing Wall Plaza within it. Accessing the Wailing Wall necessitates a progression through various stages, from arriving in Jerusalem, entering the Old City through one of its gates, traversing the alleyways to the security checkpoint at the plaza’s entrance, proceeding through the plaza toward the prayer area, and finally reaching the Wall itself. This journey, often influenced by practical considerations such as security, establishes a hierarchical structure of sanctity akin to a hero’s journey with distinct stages. This hierarchy resonates with the multifaceted aspects of holiness within us, including the super-ego and transpersonal consciousness alongside the ego and id.

The journey to the Kotel encompasses three primary stages, each representing distinct levels of Sacredness: the expansive city of Jerusalem, the ancient walls encircling the Old City, and the Sacred site itself. This tripartite division finds resonance in the phenomenology of other sacred sites such as the Church of the Sepulcher and the Dome of the Rock. The number three holds typological significance and recurs in many Sacred places. A contemporary visitor to Jerusalem traverses three concentric circles of increasing holiness, reinforced by the prominence of the walls enclosing the Old City, embellished with surrounding gardens. The presence of thresholds, such as the city gates, and the unique nature of the Sacred site further delineate these stages. Collectively, these elements contribute to the aura of Sacred places and cultivate a sense of holiness.

The contention is that without the distinction between the modern city and the ancient city, without the imposing gates marking the entrance to the old city, without the unique atmosphere of the alleyways leading to the wall, and without the personal security checks required at the entrance to the plaza of the Wailing Wall, the experience of visiting it would be fundamentally altered.

Borders, boundaries, and thresholds play pivotal roles in the phenomenology and materialization of the Sacred. The division within the Wailing Wall plaza serves to cultivate a selective and dynamic ambiance. Yosef Schenberger, the planner of the plaza, envisioned the lower square as akin to a synagogue and the upper square as resembling a synagogue courtyard, with the entire complex embodying a Sacred space characterized by varying degrees of holiness, reminiscent of the Temple. On days of large gatherings, such as holidays, prayers extend to the upper square. Conversely, on regular days, the upper plaza welcomes all without restrictions, serving as a space for communal gatherings and national ceremonies (e.g. Holocaust Memorial Day), while the lower plaza remains dedicated to holiness and prayer. However, akin to the Temple courtyard’s “integral part of the Sacred place, where some of the main Religious and social ceremonies were held, so the synagogue courtyard was also used as a part of the building itself”[23]. Thus, the upper plaza complements the lower plaza, intertwining the social and national dimensions with the religious and spiritual aspects. This interconnectedness between parts forms a cohesive organism, reflecting the principles of fractal complexity, which imbue the world image with vitality and endow the place with charisma.

Upon entering the Wailing Wall plaza, one is transported into a distinct realm where various interconnected parts coexist. The prayer area itself resembles a divided synagogue, with separate sections for men and women, instilling a sense of geometry and order. Adjacent to it lies a spacious public square, alongside essential amenities such as bathrooms and toilets. Surrounding the plaza are diverse religious structures like the Kotel yeshiva, with the hidden entry to the Kotel tunnels nearby. Open archaeological excavations lend an aura of antiquity to the surroundings, while a narrow curved bridge offers a vantage point overlooking the plaza, leading to the Temple Mount. Additionally, the wide esplanade hosts various gatherings and occasional temporary structures. The upper plaza harmonizes with the lower plaza, delineated by an artistic fence, enhancing the interconnectedness of the space.

To reach the holiest part of the Wailing Wall, which is the wall itself, one embarks on a transformative journey akin to that of a hero [24]. Upon entering the prayer area, one traverses another threshold, symbolized by the necessity to adjust clothing – men don a Kippa while many women wear scarves. The descent to the prayer space, the call for silence, and the arrival at the wall adorned with unique stones and tucked notes, collectively alter the visitor’s state. This effect is not solely attributed to the two millennia of exile and the connection to the Temple but also to the intricate layout and complexity of the place, augmented by the Sacredness Generator Fractal Complexity it embodies.

The Sacredness Generator Fractal Complexity is evident in the deliberate division of the Wailing Wall plaza into two tiers of sanctity. According to Shmuel Bhatt, Zerakh Verhaftig, the Minister of Religious Affairs during the site’s planning, justified the creation of distinct levels near the Wailing Wall by stating, “So that the crowd can approach with reverence, even in the Holy of Holies there should be preparation… there should be steps” [25]. The planner and architect, Yosef Schenberger, envisioned the area nearest to the wall as a kind of synagogue, while the square to the west of it was conceived as a synagogue courtyard. The contrast between these two areas was underscored by the introduction of varying height levels and an ornate iron fence. Furthermore, the courtyard serves as a transitional space, a buffer zone between the street and the synagogue, serving as an introduction or preparation before the worshiper enters the sanctuary within. Schenberger elaborates on this notion, stating, “This preparation includes the preparation of the body: the removal of dust, the adjustment of clothing, and a place for handwashing before prayer. The physical preparation of the body also leads to the preparation of the soul” [26].

In conclusion, the separation between the two levels of the Wailing Wall plaza, as well as the demarcation between the site and its surroundings, coupled with the intricacy of the site’s layout, its expansive size, and the multitude of components within it, collectively engender a Sacredness Generator Fractal Complexity. This complexity is further accentuated by the dimensions of the Wailing Wall, the geometric ratios inherent within it, and the proportions of the plaza, among other factors. In this context, the fractal resembles the Temple, where various degrees of holiness were delineated: the Ezra (courtyard), the Hall, and the Holy of Holies. These different parts of the Temple symbolize aspects of the human body (with the Holy of Holies representing the head, the Hall signifying the body, and the columns Boaz and Yachin in the courtyard symbolizing the legs), as well as elements of the world itself.

In this context, it is worth noting a remarkable observation: the dimensions of the Kotel plaza coincide with those of the Ezra (courtyard) in the Temple. The width of the Ezra was 62 meters, approximately equivalent to the length of the Wailing Wall itself (60 meters, an unalterable figure). Similarly, the length of the Ezra was 85 meters, mirroring the exact length (within centimeters) of the combined lower and upper parts of the Kotel plaza. As far as my knowledge extends, there was no deliberate intention in the planning to achieve this alignment. Consequently, the question arises: could this alignment be more than mere coincidence?

In conclusion:

With the construction of the Wailing Wall Plaza, a new phenomenology of the Sacred emerged, coinciding with the escalating national, cultural, and religious significance of the site, spurred by the miraculous events of the Six-Day War and the burgeoning religious trends within the State of Israel. The Kotel garnered heightened attention due to its revamped physical configuration. While always serving as a site of prayer and pilgrimage, a poignant reminder of the Temple, recent years have witnessed the development of folklore and customs around the Wailing Wall that were absent in earlier times. These developments are subconsciously influenced by the deliberate and unconscious placement of Sacredness generators during the reconstruction process.

The current layout of the Wailing Wall Plaza lends itself to the possibility of experiencing inner mystic religious encounters during visits, provided they are individual and uninterrupted, allowing for full immersion in the site. The Sacredness generators present within the vicinity have the potential to evoke such experiences in certain individuals. While there are also communal religious experiences associated with public prayers and rituals at the Wailing Wall, this aspect warrants exploration in a separate article. This article focuses on the individualistic approach to religious experiences and recognizes them as a universal inherent capacity of humanity, transcending place, culture, and time.

Bibiliography

אוטו, רודולף, הקדושה: על הלא־רציונלי באידיאת האל ויחסו לרציונלי, תרגמה: מרים רון, תל־אביב: כרמל, 1999.

אליאדה, מירצ’ה, תבניות בדת השוואתית, תרגם: יותם ראובני, תל־אביב: נמרוד, 2003.

אריאל, ישראל, בית המקדש בירושלים, ירושלים: מגיד, 2005.

בהט, דן, “לתולדות התקדשותו של הכותל המערבי”, בתוך: אלי שילר וגבריאל ברקאי, הכותל המערבי, ירושלים: אריאל (תשס”ז), עמ’ 40-33.

בהט, שמואל, “‘להבדיל בין קודש לחול’: עיצובה של רחבת הכותל המערבי אחרי מלחמת ששת הימים ומשמעויותיו”, קתדרה 174 (תש”ף), עמ’ 181-155.

בן אריה, זאב, מאפייני קדושה במקומות קדושים בישראל, חיבור לשם קבלת התואר מוסמך האוניברסיטה, אוניברסיטת חיפה, 2019.

בר, דורון, לקדש ארץ: המקומות הקדושים היהודיים במדינת ישראל, 1968-1948, ירושלים: יד יצחק בן־צבי, תשס”ז.

ג’יימס, ויליאם, החוויה הדתית לסוגיה: מחקר בטבע האדם, תרגם: יעקב קופליביץ, מהדורה שנייה, ירושלים: מוסד ביאליק. 1959.

יונג, קרל גוסטב, פסיכולוגיה ודת, תל־אביב: רסלינג, 2005

ליביו, מריו, חיתוך הזהב: קורותיו של מספר מופלא, תרגם: עמנואל לוטם, תל־אביב: א. ניר, תשס”ג.

קולינס־קריינר, נגה, המאפיינים והפוטנציאל התיירותי של עלייה לרגל לקברי צדיקים, דוח סופי מוגש למשרד התיירות, חיפה: אוניברסיטת חיפה, 2006.

Eliade, Mircea, The Sacred and The Profane: The Nature of Religion, tr. Willard R. Trask, New York: Harcourt, 1959.

Rennie, Bryan S., Reconstructing Eliade: Making Sense of Religion, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1996.

footnotes

[1] Indeed, testimonials such as this one from TripAdvisor highlight the profound impact that individual visitors experience at the Western Wall. This particular review, dated September 22, expresses deep emotional connection and spiritual resonance with the site. The reviewer, despite not being Jewish, was deeply moved by the devotion and Sacredness of the place, even spending two consecutive nights praying there for extended periods. Such accounts underscore the universal allure of Sacred places and the transformative power they hold for individuals, transcending cultural or religious affiliations.

[2] מירצ’ה אליאדה, תבניות בדת השוואתית, תרגם: יותם ראובני, תל־אביב: נמרוד, 2003, עמ’ 17-15.

[3] האזכור הראשון הוא מהמאה החמש־עשרה, לפי מאמרו של דן בהט, “לתולדות התקדשותו של הכותל המערבי”, בתוך: אלי שילר וגבריאל ברקאי, הכותל המערבי, ירושלים: אריאל (תשס”ז), עמ’ 34.

[4] Before this was not possible because the place was apparently full of buildings

[5] Ibid 206

[6] Ibid 210

[7] In the galleries in the Jewish Quarter you can find many paintings of the Wailing WAll

[8] בהט, “להבדיל בין קודש לחול”, עמ’ 161

[9] דורון בר, לקדש ארץ: המקומות הקדושים היהודיים במדינת ישראל, 1968-1948, ירושלים: יד יצחק בן־צבי, תשס”ז, עמ’ 214.

[10] אליאדה, תבניות בדת השוואתית, עמ’ 137

[11] Rennie, “Mircea Eliade and the Perception of the Sacred in the Profane”, p. 76

[12] בהט, “להבדיל בין קודש לחול”, עמ’ 161.

[13] https://www.textologia.net/?p=5875

[14] מריו ליביו, חיתוך הזהב: קורותיו של מספר מופלא, תרגם: עמנואל לוטם, תל־אביב: א. ניר, תשס”ג, עמ’ 193-189.

[15] שם, עמ’ 83. רואים זאת ביחס שבין הפאונים האפלטוניים.

[16] This is evident from the correspondence with Dr. Bhatt in the e-mail on February 12, 2023.

[17] בהט, “להבדיל בין קודש לחול”, עמ’ 159.

[18] Kings 1. 8

[19] בהט, “להבדיל בין קודש לחול”, עמ’ 143.

[20] קולינס־קריינר, המאפיינים והפוטנציאל התיירותי של עלייה לרגל לקברי צדיקים, עמ’ 33.

[21] Ibid p. 34

[22] יונג, קרל גוסטב, פסיכולוגיה ודת, תל־אביב: רסלינג, 2005

[23] בהט, “להבדיל בין קודש לחול”, עמ’ 168.

[24] קמפבל, ג’וזף, הגיבור בעל אלף הפנים, תרגום: שלומית כנען, תל־אביב: בבל, 2013.

[25] בהט, “להבדיל בין קודש לחול”, עמ’ 167.

[26] Ibid p. 168