Does God dwell in the house?

Why construct a house for God when even the heavens and the earth cannot contain Him? This query is posed by King Solomon himself, precisely during the dedication ceremony of the Temple. Solomon’s response is that the Temple acts as a conduit for prayers directed to God; it beckons God’s attention, with His ear and eye turned towards this sacred place, where He listens to the prayers offered and grants forgiveness. Yet, the answer is more complex than it seems, for in the same dedication speech (1 Kings 8), there is mention of how, upon the completion of the Temple and the placement of the Ark of the Covenant inside, a cloud filled the sanctuary, compelling everyone to exit due to the overwhelming presence. This suggests that the Temple was constructed as a dwelling for this divine presence, indicating that the Temple is indeed a house for God, rather than merely a conduit for prayers.

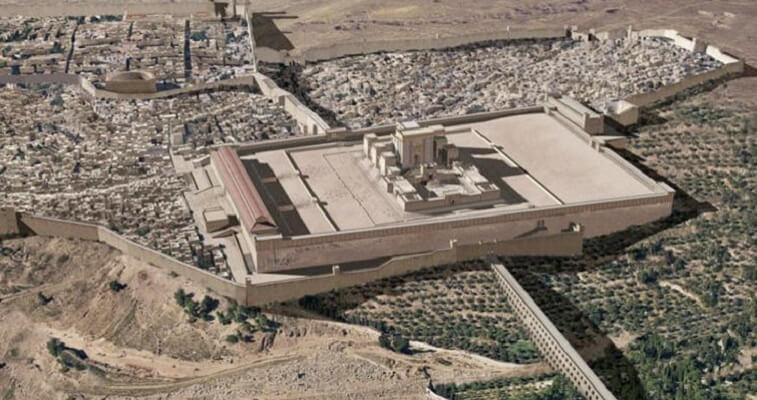

Therefore, the Temple in Jerusalem can be viewed from two distinct perspectives: the mystical perspective, which regards the Temple as a symbol and a means to connect directly with God; and the magical perspective, which perceives the Temple as a dwelling for an energetic presence, a manifestation of God on earth, where ten supernatural miracles occur daily. These viewpoints are reflected in the blessing and dedication speech of the Temple by King Solomon, showcasing the evolving perception and understanding of temples in the ancient world.

At the dedication of the Temple, Solomon poses a profound question: “But will God indeed dwell on the earth? behold, the heaven and heaven of heavens cannot contain thee; how much less this house that I have builded?” (1 Kings 8:27). The response to this inquiry is found in Solomon’s prayer: “And hearken thou to the supplication of thy servant, and of thy people Israel, when they shall pray toward this place: and hear thou in heaven thy dwelling place: and when thou hearest, forgive” (1 Kings 8:30). Thus, the house serves merely as a conduit through which the prayers of the people are heard; God, from His abode in the heavens, listens and offers forgiveness.

This is what Solomon is saying: “If any man trespass against his neighbour, and an oath be laid upon him to cause him to swear, and the oath come before thine Altar in this house: Then hear thou in heaven, and do, and judge thy servants, condemning the wicked, to bring his way upon his head; and justifying the righteous, to give him according to his righteousness. When thy people Israel be smitten down before the enemy, because they have sinned against thee, and shall turn again to thee, and confess thy name, and pray, and make supplication unto thee in this house: Then hear thou in heaven, and forgive the sin of thy people Israel, and bring them again unto the land which thou gavest unto their fathers. When heaven is shut up, and there is no rain, because they have sinned against thee; if they pray toward this place, and confess thy name, and turn from their sin, when thou afflictest them: Then hear thou in heaven, and forgive the sin of thy servants, and of thy people Israel, that thou teach them the good way wherein they should walk, and give rain upon thy land, which thou hast given to thy people for an inheritance. If there be in the land famine, if there be pestilence, blasting, mildew, locust, or if there be caterpiller; if their enemy besiege them in the land of their cities; whatsoever plague, whatsoever sickness there be; What prayer and supplication soever be made by any man, or by all thy people Israel, which shall know every man the plague of his own heart, and spread forth his hands toward this house: Then hear thou in heaven thy dwelling place, and forgive, and do, and give to every man according to his ways, whose heart thou knowest; (for thou, even thou only, knowest the hearts of all the children of men;)” (1 Kings 8:31-39).

Based on this description, the Temple serves as a bastion of justice, where the wicked face their due consequences, and the righteous receive support and acceptance. Furthermore, the Temple’s presence fosters a symbiotic relationship among natural forces, the divine, and humanity. This relationship suggests that if humans maintain the sanctity of God’s house and adhere to the commandments (mitzvot), then nature will reciprocate with timely rain and plentiful harvests, warding off natural calamities and diseases. This covenant extends to human ecology as well, implying that as long as the Temple is preserved and the Israelites live according to the ethical standards it embodies (such as those outlined in the Ten Commandments), they will enjoy protection from adversaries and experience peace and harmony in their lives.

At its core, the Temple serves as a venue where divinity can manifest itself to humanity, allowing God to understand the hearts of individuals and guide them towards fulfilling their destinies through the intermediation of the temple. Conversely, it offers humans the opportunity to demonstrate their worthiness in God’s presence. Although the personal guidance provided by the monotheistic God is an internal process that fosters a union with the divine, it nonetheless relies on the presence of the Temple and adherence to the commandments. In essence, the Temple acts as a conduit for achieving a mystical and direct experience of the sacred, facilitating a profound religious connection.

In the subsequent passages, Solomon articulates a notion that highlights the universality of the Temple, marking it as a house of prayer for all peoples: “Moreover concerning a stranger, that is not of thy people Israel, but cometh out of a far country for thy name’s sake; (For they shall hear of thy great name, and of thy strong hand, and of thy stretched out arm;) when he shall come and pray toward this house; Hear thou in heaven thy dwelling place, and do according to all that the stranger calleth to thee for: that all people of the earth may know thy name, to fear thee, as do thy people Israel; and that they may know that this house, which I have builded, is called by thy name.” (1 Kings 8:41-43). This signifies that the Temple serves not just as a place of worship for the Israelites but for all humanity. Following Solomon’s vision and the prophets that succeeded him, the Temple is envisioned to become a house of prayer for all nations, fostering global peace, even extending to harmony among animals.

Solomon’s underlying belief is that God does not dwell in the Temple itself but within the individual, with the Temple serving merely as a means of facilitating connection with Him. The Temple provides a sacred space where prayers and pleas can be presented before God, who in turn, responds or at least listens to these entreaties. This concept is reinforced when, after Solomon’s prayer, God appears to him a second time in Gibeon, affirming: “I have heard your prayer and your supplication that you have made before Me; I have consecrated this house that you have built by putting My name there forever, and My eyes and My heart will be there perpetually” (1 Kings 9:3). This declaration underscores the enduring presence and attention of God towards the Temple, highlighting its role as a perpetual point of divine connection and oversight.

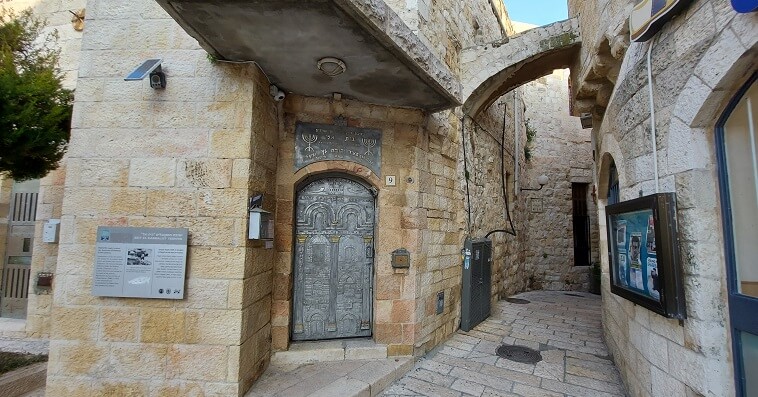

Solomon’s perspective on the Temple in Jerusalem laid the groundwork for a tradition of directing prayers towards Jerusalem, a practice that dates back to the era of the First Temple. This tradition is vividly illustrated in the prayer of Daniel, who, while in exile, prays towards Jerusalem. His prayer symbolically connects him with the heavenly Temple, seen as the counterpart and completion of the earthly Temple in Jerusalem, which was likely destroyed by the time of his prayers. Daniel’s act of praying towards the concept of a Temple underscores a profound shift towards a spiritual and ideational approach to worship. This tradition of orienting prayers towards Jerusalem, motivated by the historical and spiritual significance of the Temple, continues to be a central aspect of prayer practice to this dayץ

The practice of directing personal prayers towards the Temple in Jerusalem is distinctively Jewish, setting it apart from other religious practices in the ancient world, where prayer within the temples was conducted in the immediate presence of the deities housed therein. Solomon’s emphasis on the Temple as merely a conduit for prayer to God not only refines but also elevates its significance. This approach eventually leads to the spiritualization of the Temple, transitioning its role from a concrete physical entity to a more abstract concept.

The inclination to view the Temple in a mystical light, as a medium for connection and a place of prayer rather than solely as a site for the physical presence of God and the performance of sacrifices, became more pronounced during the Second Temple period. This shift coincided with the decline of ancient magical cultures of Egypt and Mesopotamia and their replacement by the vibrant Hellenic culture. Hellenism, with its opposition to magical practices and its promotion of philosophy, science, and mystery cults, provided a contrasting backdrop. Amidst the influence of Hellenic culture, Judaism began to transform its foundational elements, placing greater emphasis on study, prayer, and discussion rather than on ritual worship. This transition reflects a significant evolution in the religious and cultural practices of the Jewish people, adapting to the changing intellectual and spiritual landscape of the time.

Solomon’s invocation concerning the Temple marks a pivotal moment in history, indicating a shift from a focus on magical practices to a symbolic and mystical-spiritual engagement with religion and sacred spaces. The Temple evolves into a symbol for the Jewish people, serving as a conduit for prayer and, eventually, as a gateway to mystical experiences that allude to an abstract, heavenly Temple rather than just the tangible structure on Earth. This transformation signifies the Temple’s transition from a place believed to house a supernatural presence to a concept and symbol embodying deeper spiritual meanings and connections. This development in the perception of the Temple reflects broader changes in religious thought and practice, highlighting an increasing inclination towards the abstract and the transcendent in the spiritual landscape.

The Temple transforms into a celestial Temple

In the preceding chapters, we focused on the Temple in its physical form, which might have given the impression that the building itself holds significance. However, this is not the case. My fundamental belief is that the true essence of the Temple resides within individuals, rather than in wood and stone. When Moses stands at Mount Sinai, the concept is that God will come to dwell among humanity, as expressed in the verse “make for me a Temple and I will dwell among them”. Yet, the people were fearful. Hence, God provided them with a intermediary tool they could relate to as a means of connecting with Him – a Tabernacle and a Temple. This was necessary because they emerged from Egypt, where the prevailing culture revolved around magic and Temples.

Solomon constructed the Temple as the final act in the Creation process. However, even during the consecration blessing of the Temple, he acknowledges that God does not solely reside within its walls. Consequently, subsequent to the Temple’s construction, a transformative journey began, gradually elevating it towards a heavenly state. This evolution aims to restore the Sacred to its rightful abode, within humanity and in the celestial realm. Facilitated by the great prophets of the first temple era, this process encompasses both the prophesied destruction of the physical structure and the presentation of a spiritual Temple—an ideal reality anticipated to manifest in the ultimate culmination of days.

At its inception, Judaism operated as a Halacha-based religion, emphasizing worship, morality, and purity, as delineated in the Torah’s laws, with the Temple in Jerusalem serving as the focal point of worship. However, during its evolution, another dimension was incorporated into Judaism: the proactive morality advocated by the prophets. While drawing inspiration from the Temple, this moral aspect diverged from dependence on external temple rituals, guiding individuals inward toward the intrinsic Temple within themselves.

In essence, Judaism introduced two significant departures from preceding religions: an emphasis on mysticism over magic, highlighting the belief that God resides within humanity and lacks a physical form or likeness; and a focus on morality derived from the acknowledgment that humans are created in the image of God. This emphasis on morality is reflected in commandments such as “Thou shalt not murder” found in the Ten Commandments. With the emergence of the great prophets, another dimension was added: active morality, not merely adherence to mitzvot (laws), but proactive engagement in rectifying the world’s wrongs. Individuals were called to actively seek opportunities to do good in the world. This principle is evident in the teachings of Isaiah, the foremost of the great prophets, who exhorted: “Learn to do right; seek justice. Defend the oppressed. Take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow” (Isaiah 1:17). Isaiah explicitly challenged the prevailing temple worship of his time, declaring: “The multitude of your sacrifices—what are they to me?” says the Lord. “I have more than enough of burnt offerings, of rams and the fat of fattened animals; I have no pleasure in the blood of bulls and lambs and goats” (Isaiah 1:11).

The prophets vehemently opposed the prevailing belief among the Israelites that sacrifices and pilgrimages to the Temple would provide blanket protection from all evils. They challenged the notion of worship as the ultimate prerequisite for divine favor and criticized the hypocrisy of the priests, as well as the idolization of the Temple and Jerusalem. Isaiah, followed by Jeremiah and other prophets, conveyed the message that mere acts of worship held no inherent value in the eyes of God. Rather, what truly mattered were the principles of humanity, justice, and morality. They asserted that the Temple itself held no inherent sanctity, and emphasized the importance of adhering to the moral laws encapsulated in the Ten Commandments.

The great prophets foresaw that Israel’s transgressions would result in the Temple’s destruction, a consequence brought about by God Himself, intended as a lesson for the children of Israel. However, they prophesied the eventual construction of another Temple, one characterized by greater justice and righteousness. Thus, the local God transcends to become the God of history, utilizing the actions of mighty powers as instruments to discipline the people of Israel and guide them back to the correct path. The future Jerusalem embodies a celestial ideal, where nations will no longer wage war against each other, and harmony will reign, symbolized by the imagery of the wolf lying down with the lamb.

The great prophets primed the hearts and minds of the Israelite people for the impending destruction of the physical Temple. They severed the people’s reliance on the tangible structure and elevated it to an ideal of a spiritual heavenly Temple. By universalizing God, independent of any specific time or place, the prophets enabled the Israelites to sustain their faith and identity even after the Temple’s destruction. This allowed them to persevere on their path of advancement despite exile, as they clung to the concept of the Temple rather than its physical manifestation.

Isaiah stands as the foremost among the great prophets, delivering his prophecies against the backdrop of the Assyrian Empire’s expansion, the fall of the Kingdom of Israel in 730 BC, Sennacherib’s campaign against Judah, and the looming threat of Jerusalem’s conquest, ultimately averted by miraculous intervention. It appears that God’s wrath is stirred, leaving the Jews puzzled about His desires: He rejects sacrifices, offerings, incense, and even prayers. Instead, His demand is for justice, benevolent deeds, pure intentions, and proactive care for orphans and widows. This marks Isaiah’s profound innovation, injecting a dimension of active morality and universality into Jewish religion. Henceforth, the Jews are called to set an example for the entire world, their spiritual and moral message transcends mere ritual and is intended for all of humanity.

Following Isaiah, the next significant prophet is Jeremiah. His prophecies unfold against the backdrop of the waning days of the Kingdom of Judah. This period is marked by the religious reforms initiated by Josiah, his tragic demise in the Battle of Megiddo, the ascent of the final Jewish monarchs, the land’s conquest, the fall of Jerusalem, the Temple’s destruction in 586 BC, and the subsequent Babylonian exile. Jeremiah bore witness to the fulfillment of his prophecies, experiencing firsthand the Temple’s destruction and the exile. He himself was later exiled to Egypt, where some of his later prophecies offered solace and comfort.

Jeremiah boldly opposed the worship practices in the Temple and the reliance on the Ark of the Covenant while it still resided there. Some speculate that he might have been the individual who concealed the Ark beneath the Temple’s courtyards. Since Jeremiah’s time, the Ark has vanished from biblical mention. He envisioned a profound transformation in humanity: “Lord, I know that people’s lives are not their own; it is not for them to direct their steps” (Jeremiah 10:23). This change necessitated a new moral code and religious comprehension, leading to the establishment of an eternal covenant between God and the children of Israel: “I will make an everlasting covenant with them: I will never stop doing good to them, and I will inspire them to fear me, so that they will never turn away from me” (Jeremiah 32:40). This concept mirrors a new creation of humanity, with potentially far-reaching implications.

According to Menashe Dubshani, Jeremiah invalidated the sanctity attached to physical locations and instead emphasized the historical covenant forged between God and the Israelites at Mount Sinai. For this reason, he does not explicitly reference Mount Sinai, indicating that Jerusalem and the Temple hold little significance in his teachings. This perspective allows for a connection with God even in exile. Jeremiah envisioned a new covenant inscribed on the hearts of individuals rather than on stone tablets. He underscored the inner, universal essence of Jewish faith, devoid of geographical constraints, spanning from the Exodus from Egypt to the end of days. However, despite this emphasis, Jeremiah’s prophecies retained a national focus, suggesting that the annulment of the sanctity of place is not absolute, and Jerusalem held some importance to him.

Jeremiah commenced his prophetic career during the reign of Josiah. Several years into his ministry, the King discovered the book of Deuteronomy within the Temple, a manuscript dating back to the days of Solomon. This discovery prompted a comprehensive religious reform. The book, also known as the “Mishne Torah,” was publicly read in a solemn ceremony, serving as a pivotal moment for purifying the Temple and the entire nation from foreign religious influences. Its laws and narratives introduced a new dimension to religious practice, serving as a moral compass accessible to all. This volume concentrated and elaborated on the stories found in the Torah, highlighting themes of social justice and the significance of the Temple. Regarded as Moses’s final address and ethical testament, the book made the teachings of the Torah widely available to the masses of Israel. It became a spiritual resource carried by the exiles into captivity, its moral guidance, alongside the prophets’ messages of both impending doom and consolation, aiding in their endurance through the devastation.

During the same period as Jeremiah, another significant prophet emerged: Ezekiel ben Buzi, who also served as a priest. The fact that both Jeremiah and Ezekiel were priests underscores the shift in religious attitude and morality advocated by the prophets, which permeated priestly circles. This shift marked a transition in the nature of priesthood—from a focus on ritualistic duties within the Temple to a more holistic approach resembling that of modern-day rabbis, seeking social and personal reforms. These new prophetic priests served as both wisdom teachers and mystics, delving into the mysteries of the Merkavah (divine chariot) vision. While tied to the Temple, they transcended its physical confines through their reliance on a spiritual Temple.

The Temple served as a source of inspiration for those who frequented its courts and chambers, likely influencing the prevalence of priests among the ranks of prophets. However, following their prophecies, what emerged as paramount was not the physical Temple itself but rather the belief in the existence of a spiritual Temple—an idealized concept of the Temple embodied in a new body of teachings. Essentially, the earthly Temple served as a blueprint for an ideal spiritual Temple that currently exists in the higher realms but is destined to manifest on earth in the future. Thus, after the Temple’s destruction, the prophet Ezekiel received a vision of the Temple for the future.

Ezekiel, a priest from the Temple, experienced exile to Babylon alongside Jehoyachin. His prophetic ministry commenced several years before the Temple’s destruction in 586 BC and continued for many years, including during his time in exile. Ezekiel’s prophecies are characterized by vivid visions, notably the merkavah (chariot) vision depicted in the first chapter, which holds significant importance in Jewish mystical experience. In this vision, the heavens open, allowing the prophet to ascend to heaven and behold the structure of the divine realms. However, before reaching this celestial vision, Ezekiel encounters three formidable barriers, vividly described in verse 4: “I looked, and I saw a windstorm coming out of the north—an immense cloud with flashing lightning and surrounded by brilliant light. The center of the fire looked like glowing metal.”

The cloud and the fire symbolize the presence of the Shekinah in the Temple, while the storm represents the inner turmoil experienced by those who approach the Sacred. The wind of the storm signifies the initial encounter with Holiness, characterized by a state of mental emptiness where thoughts are suspended. In this state, the inherent spiritual vibrations within the soul intensify. The condition of the cloud represents a phase where all thoughts are quieted and expelled from the mind, resulting in a kind of mental opacity that precludes conventional perception, yet allows for a profound experience of God and His teachings. This state may be akin to the fog within the devir. The blazing fire symbolizes the encounter with the realm of energies, often leading to overwhelming emotional intensity that can be challenging to endure. This spiritual light mirrors the presence of God’s glory between the two cherubim above the Ark of the Covenant.

Ezekiel’s pioneering contribution lies in his visionary exploration of the divine realms, offering an alternative to the physical Temple as a conduit for spiritual experience. His revelation paved the way for the conception of a heavenly Temple. Indeed, the Merkavah system, detailed in Ezekiel’s vision, largely supplanted the physical Temple, encompassing its various facets. Mystics from the later period of the Second Temple era expanded upon Ezekiel’s vision by incorporating additional passages from biblical literature into their esoteric teachings. These included descriptions of angels offering praises before God, Daniel’s prophetic visions, passages from the Psalms, the first chapter of Genesis, the Song of Songs, and more. These diverse sources were interwoven to craft a captivating and enigmatic depiction of the celestial realm. At the heart of this vision stands the Merkavah, with the throne of honor atop which the Lord resides, surrounded by encampments of angels—some holding official roles, while others are devoted to praising and singing before Him. This visionary tableau has largely supplanted the physical Temple as the ultimate aspiration and means of connecting with God.

Parallels can indeed be drawn between Ezekiel’s visions and the teachings of the spiritual schools of ancient Egypt, particularly the Hermetic tradition, as well as other spiritual schools in the ancient world. These teachings employ symbols, archetypes, numbers, letters, and even colors to elucidate the process of creation and the principles governing the universe. According to these teachings, everything originates in the energetic-spiritual realm before manifesting in the physical world. Human existence follows a similar pattern: individuals are initially conceived as spiritual beings, embodying the archetype of the “ancient of all ancients,” before assuming physical form created from the earth. Just as the teachings of ancient spiritual traditions prioritize the spiritual over the material, Judaism places importance on the spiritual Temple, which transcends physical constraints. Therefore, even in the absence of the earthly Temple, the spiritual essence and teachings of Judaism persist, ensuring its continuity and resilience.

Freemasons and the Temple

According to the Masonic tradition, the knowledge of Sacred architecture originated in Egypt and was later transmitted to the Phoenicians, eventually reaching the builders of the Temple in Jerusalem. The builders of the pyramids and temples in Egypt were renowned as great magicians and advanced scientists. Through their structures, they expressed the dimensions of the earth, the structure of the universe, and the nature of humanity, creating environments conducive to human development. Solomon and Hiram Abiff continued in their footsteps. This is echoed in 1 Kings 7:13-14, which describes how King Solomon enlisted Hiram, a skilled craftsman in bronze, to assist in the construction of the Temple: “King Solomon sent to Tyre and brought Hiram, whose mother was a widow from the tribe of Naphtali and whose father was from Tyre and a skilled craftsman in bronze. Hiram was filled with wisdom, with understanding, and with knowledge to do all kinds of bronze work. He came to King Solomon and did all the work assigned to him.”

In 2 Chronicles 2:13, it is stated: “I am sending you Hiram-Abiff, a man of great skill, whose mother was from Dan and whose father was from Tyre. He is trained to work in gold and silver, bronze and iron, stone and wood, and with purple and blue and crimson yarn and fine linen. He is experienced in all kinds of engraving and can execute any design given to him. He will work with your skilled workers and with those of my lord, David your father.”

Both the Book of Chronicles and the Book of Kings mention two individuals named Hiram: one is Hiram, King of Tyre, and the other is the craftsman he dispatched, known as Hiram Abiff. The latter Hiram is central to the Masonic tradition, and while the Bible provides limited details about him, Freemasons have drawn from additional sources and developed their own narratives. They have crafted an elaborate mythology surrounding his character, which plays a significant role in Masonic lore and rituals.

The story, as it is recounted in various Freemasonic lodges, typically features a hero named Hiram Abiff or Adoniram, with “Abiff” meaning “father.” Hiram hails from the Phoenician royal lineage and possesses expertise in the esoteric secrets of Sacred architecture, including numerology, geometry, measurement, and their practical application in art and construction. He assumes a leadership role in overseeing the construction of the Temple and infuses it with knowledge of the spiritual realms, influencing its dimensions, proportions, layout, architectural design, and choice of materials.

The builders of the Temple were organized into three distinct groups and ranks: apprentices, workers, and masters, all of whom were free men. Each group was exposed to secret knowledge commensurate with their rank, facilitating their personal development. Given the vast number of workers involved, Hiram did not know each one personally. To differentiate between the ranks, each was assigned a specific password: “Boaz” for apprentices, “Yachin” for workers, and initially, “Jehovah” for the masters. Alongside these passwords, each rank was also associated with a unique sign, hand posture, and specific handshake. The words “Boaz” and “Yachin” derive from the names of the two copper pillars Hiram constructed at the temple’s entrance, as described in 1 Kings 7:21: “He erected the pillars at the portico of the temple. The pillar to the south he named Yachin and the one to the north Boaz.”

During the distribution of wages to the workers, each worker would approach Hiram, presenting the appropriate signs and uttering the password to receive their salary. However, on one occasion, Hiram was accosted by three workers who demanded the master’s password and signs. In their attempt to coerce him, one struck Hiram on the head with a hammer, another on the Temple with a plumb, and the third on the other Temple with a level. As a result of this attack, Hiram perished and was laid to rest on the slope of the Mount of Olives. The story continues with the discovery of his body, but its significance lies largely in its symbolism. Embedded within the narrative are the secrets of initiation into the higher ranks, wherein a symbolic death and resurrection occurred—a motif commonly found in initiation rituals across various ancient traditions.

According to Freemasonic tradition, during the construction of Herod’s Temple, there were individuals among the builders who possessed esoteric knowledge. This knowledge had been passed down through the ages by guilds of builders, ensuring its continuity. Following the first temple period and Solomon’s reign, Freemasonry found a foothold in Rome, among associations of builders who were formally recognized and granted independent status by King Numa Pompilius as early as the 7th century BC. As a result, these builders adopted the religion of Mithras, the Persian sun god, which contained elements of Masonic initiation. A school of Sacred architecture was established at Lake Como, producing skilled artisans such as Maimus Gracchus, who played a role in the construction of Herod’s Temple.

In Masonry, the three ranks—apprentice, fellowcraft, and master—are symbolically linked to the virtues of faith, hope, and charity (generosity). This symbolism finds expression in the design of Solomon’s Temple, which comprises three main sections: the ground floor, the middle chamber, and the Holy of Holies. These three levels serve as the foundation for the three degrees in Freemasonry, corresponding to the three stages of initiation, and the three systems of symbols employed within the craft. They represent ascending levels of awareness and spiritual enlightenment.

In operative Freemasonry, the apprentice’s task involved refining raw stone into building blocks using tools like the measure, hammer, and chisel. Once polished, the Freemason would then place these worked stones accurately using instruments such as a protractor, level, and plumb line. On the other hand, the master builder, after meticulously inspecting the quality of the work and selecting stones deemed suitable for use, would apply cement between them using a Masonry Trowel to join and fortify them together. As a result, the Masonry Trowel became emblematic of the master builder in Masonic tradition, symbolizing the moral imperative to foster brotherhood and kindness among fellow Masons. Consequently, the Masonry Trowel held significant symbolic importance within the fraternity.

The level, utilized to ascertain horizontal surfaces on the ground, represents the principle of equality among all individuals. It embodies the democratic ideal that inspires us to collaborate with others and collectively embrace the virtues of equality and justice. Conversely, the plumb, employed to determine vertical alignment, symbolizes the notion of nobility and our aspiration to elevate and cultivate our intellect and spirit. In Freemasonry, the Sacred Book is opened in lodges with verses from Amos 7:7-9, which depict the Lord standing beside a wall constructed accurately with a plumb line in hand, emphasizing the importance of integrity and adherence to moral principles.

The protractor serves as a symbol of the connection between the horizontal and vertical dimensions, bridging the gap between the level and the plumb. It represents the harmonious integration of two opposing vectors that would otherwise appear contradictory. The moral lesson derived from this symbolism is profound: just as the plumb and the level are united within the protractor, individuals of diverse natures and conflicting viewpoints must strive for unity. Similarly, the compass, which symbolizes earth and sky, matter and spirit, carries a special significance. Our happiness and progress in Freemasonry and in life will flourish as we integrate and blend these opposing elements together.