The Thracians

According to the currently accepted opinion (though some dispute it), the Thracian tribes arrived in the Balkans during the great migrations of the Indo-European people 3,000-4,000 years ago, settling in areas that are now Bulgaria, northeastern Greece, and the European part of Turkey. In the regions of Romania and northern Bulgaria, the Getae tribes, closely related to the Thracians, also settled. In the past, these tribes were considered barbarians, and this is how the Greeks viewed them. However, archaeological findings discovered in recent years show that they actually had an advanced material culture, developed religion, and deep spiritual teachings. The Thracian culture reached a historical peak in the 4th-5th centuries BC, influencing Greek culture and the creation of the Orphic mystery school.

The Thracians are named after Thrax, the son of Ares, the war god, who lived in Thrace. They flourished at the same time as the Mycenaean culture in the Peloponnese, the Minoan culture in Crete, Troy, and the cultures in Anatolia during the 2nd millennium BC. In the classical period (4th-6th centuries BC), they constituted an independent and powerful entity that existed alongside Athens and Sparta, adopting some elements of Greek culture. Until recently, it was thought that the Thracians did not have writing, but excavations have shown that they did, although it has not yet been deciphered. A long inscription in large, clear letters was discovered at a sacred rock site in the Rhodope Mountains, known as the Sitovo Inscription.

Greek writers describe the religion of the Thracians as follows: the Thracians despised death, mourning the birth of a baby and burying the dead with joy, which explains the amazing courage they showed in battle. They placed religious value on death and were people poor in material wealth but rich in spirit. They believed immortality was achieved while alive through a ritual of initiation.

The Thracians were known for their excessive drinking ability, and most treasures found in their tombs are wine goblets. Thus, the traditions of Dionysus found a home in Thrace, and some say they originated in the forests of Thrace. According to Herodotus, the Thracians worshiped Dionysus, Artemis, and Ares, but the king believed he was the son of Hermes.

The Thracian earth goddess had a son who was first associated with the sun and then with vegetation. In all his manifestations, he would die every year and be reborn. Later, he was associated with Dionysus or a god named Sabazios, and the center of his worship was in Perperikon in the Rhodope Mountains. The remains of his cult persist to this day in the folklore traditions of Bulgaria, such as fire-walking and the Kukeri masks.

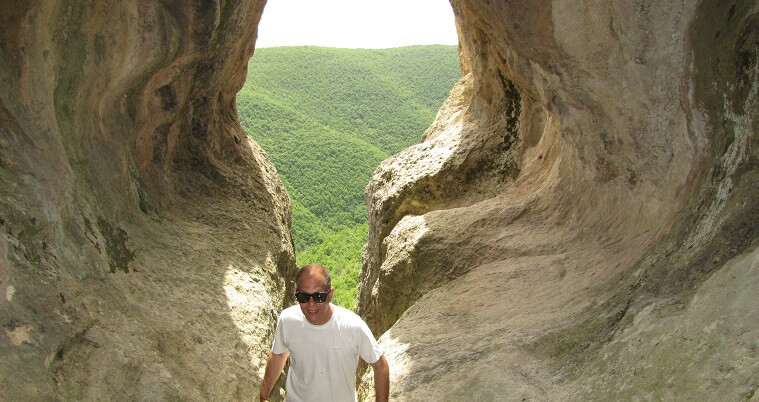

The Thracians adopted the holy places in the mountains dedicated by the ancient goddess-worshipping people and cultivated them. Some of these sites were in the form of a gate or a womb, where they were symbolically reborn during their annual celebrations. The sacred sites were connected to the forces of the sun and the moon and the energies of the earth. Eliade argues that the Thracians had a myth of a sacred marriage between the god of the storm and the sky and mother earth, corroborated by the traditions of the sacred center in Samothrace.

Thracian society was ruled by an aristocracy of priest-kings, somewhat similar to the Celtic Druids, deeply involved in religion and mysticism and seeking eternal life. The prophet and teacher of the Thracians was Orpheus, the legendary musician from Greek mythology

Indo-European Spirituality

The spirituality of the Indo-Europeans had several characteristic features: first, history was seen as circular, based on cycles, as were the life and death cycles. Time was not perceived as linear, leading from creation to redemption, as in the spirituality of the Semitic people. Additionally, the Indo-Europeans believed in an ancient struggle between good and evil. They believed that this world is only an illusion, a screen, and that there are other unseen worlds beyond this world of matter, which are the real worlds.

Indo-European culture was, to some extent, a culture of magic, but unlike Egyptian magic, it was closer to nature. They brought new religious concepts to the Balkans, including a spirituality based on a male sky god, a cyclical concept of life, and an aspiration for eternal life. The Indo-Europeans excelled in the use of iron and the domestication of horses. They had superb war skills, tribal organization, new mythologies, and language. Organized according to hierarchical social classes, they introduced advanced mental and religious concepts, a spirit of initiative and action, and a drive for fulfillment and self-improvement.

According to Professor Salman, the source of the spirituality of the Indo-European peoples was the northern School of Atlantis, which found a home in Central Asia in the area of the Trim basin, starting from the 8th millennium BC. From there, spiritual teachers were sent to establish study centers and encourage the creation of new communities worldwide. These communities developed into nomadic peoples, farmers, and builders of megaliths. Together with the worshipers of the goddess, the population of Europe was fused and created. The spiritual teachers established spiritual schools and centers of prophecy throughout Europe, forming a network of knowledge dissemination that influenced the development of human culture. Thus, when the last waves of emigrants came to the Balkans and Europe, the nations of Europe—such as the Slavs, Celts, Thracians, and Baltic peoples—were influenced by these centers of learning and initiation.

One of the spiritual centers of the Slavs was in Kiev, where the enlightened Scythians kept the wisdom of Atlantis. They called it the “Mysteries of the Hyperboreans.” The Hyperboreans were mythological people who lived beyond the source of the North Wind. The Greeks thought that the areas north of Thrace were the land of Hyperborea. Later, Scythianus became the teacher of the Scythian cavalry tribes that ruled the plains of Eurasia from the 8th to 2nd centuries BC. According to Salman, the spiritual center of the Thracian tribes was on the island of Samothrace in the northern Aegean Sea.

Orpheus

According to the classical Greek version, Orpheus was the son of the Muse Calliope and the god Apollo. According to most sources, he was born in Thrace or Peira in northern Greece. Orpheus was a favorite of the muses, who received a miraculous lyre from his father as a gift. Even as a child, he proved to be a talented musician. What he loved most of all was to play. When Orpheus played, birds stopped flying and gathered around him to listen, people paused their work to hear the wonderful melody, and everyone suddenly saw their friends in a different, positive light. The world seemed a good place to live in. Even the trees listened intently, and it felt as though the entire universe stopped in its tracks to listen. Orpheus was a wonderful musician like no other, and it seemed that when he played, he was in other worlds. Day and night, Orpheus amazed with his playing. It was his passion, his love, his life. However, there was one thing he loved even more in the world—beloved Eurydice, who also loved him.

Life seemed perfect for Orpheus: he had a profession he loved more than anything, he had uniqueness, a vocation, a destiny, and most importantly, he had love. He intended to marry Eurydice and live happily ever after. But life had other plans for him. Life has surprising turns, and in every great joy, there is a kernel of destruction. On the appointed day of their wedding, Eurydice was bitten by a poisonous snake and died. Overcome with grief, Orpheus decided to take advantage of his extraordinary musical skills and do something no one had done before—descend to the underworld and rescue his beloved from the grip of death.

Many difficulties awaited him on the way: slippery and dark slopes, unexplored abysses, the three-headed dog Cerberus that threatened to devour him, and the terrible River Styx. He overcame all these obstacles with the help of his lyre and his courage. Finally, he stood before the ruler of the underworld, Hades and Persepone, and played a sad song about the fate of human beings, who, upon barely touching happiness, have it immediately taken from them.

The music and song were so touching that even the hardened Hades shed a tear and agreed to release Eurydice from the underworld, on the condition that Orpheus would walk forward and not look back on their way up. A seemingly simple condition, but one that everyone fails to uphold.

As they ascended, after a long and arduous journey, when Orpheus finally saw the light at the end of the tunnel, he was suddenly overcome by a desire, a spirit of madness that took hold of him, and he glanced back to see if Eurydice was still with him. That was enough: Eurydice was there, but immediately she was dragged back to the underworld, and the rocks closed in on her forever. All she managed to say was, “Farewell.”

Orpheus was overcome with grief: not only had his beloved been taken from him forever, and not only had he made the long and difficult journey in vain, but it was entirely his fault, due to a momentary lapse of judgment. Orpheus could not contain the sorrow, guilt, and consequences of his actions and went out of his mind. He spent the rest of his life as a madman in the forests of Thrace until he accidentally stumbled upon an ecstatic ritual of the priestesses of Dionysus (Bacchian)—women who would get drunk and go wild in the mountains. They tore him to pieces, and thus his life ended. The enraged Dionysus sent the Maenads against him. The lyre was shattered, and his limbs were scattered everywhere. His head, thrown into the water, floated singing as far as the island of Lesbos, where a temple was erected in his honor.

This is the Greek version. According to Greek sources, Orpheus lived in the 8th century BC and is related to Homer and Hesiod (he was their spiritual father). However, it turns out that the story of Orpheus and his descent into the underworld had another version common among the Thracians. In this version, Orpheus had a different ending: he lived to a very old age and was a king, priest, healer and teacher, and prophet. Some Bulgarians believe to this day that Orpheus lived many years before the Greek era and that his place of birth and burial is in the Rhodope Mountains.

According to Professor Alexander Fol, the “father” of Thracology (the study of the history, religion, and culture of the ancient Thracians) in Bulgaria, the Thracian aristocracy believed in an original local version of Orphism learned in small and secret circles of followers. There are two Orpheuses: The Greek Orpheus is the singer, poet, and musician, while the Thracian Orpheus is a divine figure who leads people to spiritual knowledge. The Thracian Orpheus is a combination of king, priest, musician, healer and teacher of wisdom, to whom the forces of nature and the world beyond are no secret.

According to the Thracian version, after losing Eurydice, Orpheus wandered around the woods, maddened and in pain, until one night, towards dawn, he climbed a high mountain (some identify it as Tatul in the Rhodope Mountains and others as Mount Pangaion in Greece) and watched the sunrise. At that moment, he realized that everything that dies is resurrected, life is a cycle of life and death, and his attempt to preserve Eurydice in her physical form was a vain attempt doomed to failure. Death cannot be overcome, but it is possible to be resurrected in a different way, to be reborn as an eternal soul in the spiritual world. He understood that as long as Eurydice lived in his thoughts and his love, they were united forever. Orpheus discovered the secret of eternal life and spent the rest of his life teaching this discovery to others through sacred music and dance expressing universal truths. His teachings included spiritual initiation, interpretation of sacred texts, and guidance towards a life of purity in spiritual communities. Thus, the School of the “Orphic Mysteries” was founded.

According to this version, Orpheus was an enlightened teacher who received his knowledge in Egypt and the East (Persia, India). He was declared the founder of the initiations—methods that prepare a person to connect to the spiritual element within themselves. The prerequisites of Orphism included vegetarianism, celibacy, purification, study of the holy books, and belief in reincarnation and the immortality of the soul.

Orpheus is described as a musician and healer, charmer, and tamer of beasts of prey. According to Professor Martin Litchfield West, there is a connection between Orphism and shamanic practices that came to Greece from the north in the 6th-7th centuries BC. These practices included a new understanding of death and birth, dissolution and reconnection, transformations, and journeys in the spirit. All of these elements entered into Orphic literature. Thus, the severed head of Orpheus was preserved and used as an oracle, similar to how the heads of Siberian shamans were used until the 9th century and as seen in ancient Celtic tradition.

Greek mythology tells us that Orpheus participated in the Argonauts’ journey for the Golden Fleece and brought all his companions to the island of Samothrace to be initiated there. According to Professor Bremer, Orpheus set the rhythm for the rowers on the Argonauts’ ship. Musicians are outside the normal social order, as they have a special connection with the muses. Orpheus was associated with initiation and secret societies, especially those of young people. He is the founder of the mystery tradition, poet and prophet, with Homer and Hesiod being his descendants, either physical or spiritual. Orpheus is considered the first and oldest of the poets.

In the Rhodope Mountains in Bulgaria, you can find the cave from which Orpheus descended to the underworld and the place where he saw the sunrise and was enlightened. Later, he was buried in the same place, atop which is an impressive megalithic complex called Tatul. Other places associated with Orpheus in Bulgaria are the city of Plovdiv, the Seven Lakes in the Rila Mountains, and the village of Gela, where he was born. The Bulgarian people preserved this image and memory in the remote mountains, where people who consider themselves his followers still live. They know how to talk to animals as Orpheus did and use music and dance to reach ecstatic and spiritually pure states, as he taught them.

Orphic life

The Thracian aristocracy adopted, as mentioned earlier, the doctrine of Orphism and created Orphic societies open only to initiates. They practiced mystical rituals with an emphasis on dance and music and offered allegorical interpretations of mythological stories. The Orphics were vegetarians, lived a life of purity, and were involved with the worlds of energy and the afterlife. Some scholars argue they believed in a system of ten different energies that make up the world, similar to the concepts in Kabbalah.

Orphism was widespread among the Thracians, Greeks, and later throughout the classical world. Those sanctified in the way of Orpheus (the Orphians) refused to eat meat. The practical meaning of vegetarianism was the avoidance of blood sacrifices. Eating meat was linked in ancient times to myths about the gods, the deed of Prometheus, and the religious life of the Greek city. Eating meat was part of a covenant that was renewed between gods and humans through religious ceremonies. The vegetarianism of the Orphic life distinguished a person from the Greek urban culture and mythology. From a religious point of view, “the turn to vegetarianism indicates both the decision to atone for the original sin and the hope to return, at least partially, to the state of original happiness” (Eliade). The deep meaning of choosing vegetarianism was liberation from the general Greek cultural karma.

According to Eliade, several passages from Plato’s writings hint at the main Orphic concept regarding immortality: “The soul is imprisoned in the body (Soma) as the body is in the grave (Sema), hence physical existence is more like death, and the death of the body is therefore the beginning of life. However, this ‘true life’ is not achieved automatically but only through the efforts of a life of purity and initiation. The soul is judged according to its achievements and failures, and after a while, it is reincarnated.” Similar to the beliefs in the Indian Upanishads, the Orphic belief is in the indestructible existence of the soul, which causes it to reincarnate again and again until its final redemption. The essence of Orphism is refinement and development, achieved through music, dance, poetry, healing, interpretation, community life, and prophecy.

According to the Orphic myth of Dionysus Zagreus, before the current cycle of gods and men, there existed instinctive deities, twisted giants called Titans. When they heard that a divine child, Dionysus, was born, they became jealous and tore his body to pieces, swallowing the parts. However, the goddess Athena managed to save his heart and brought it to his father Zeus, who swallowed the heart and gave birth to a second Dionysus. Zeus then fought the Titans and burned them. The human race was created from the ashes of the Titans, and therefore man has both a Dionysian-divine character and a Titan-monstrous nature, because the ashes of the Titans contained the body of the child Dionysus. By purification, initiation rites, and maintaining an Orphic life, it is possible to eliminate the titanic part of oneself and achieve a Bacchic, Dionysian divine state.

Apparently, the Orphic initiation included the repetition of prayers, mantras, fasting, rituals of purification, the presentation of a drama of death and rebirth, and possibly a ritual meal. At the end of this process, one received grace and was able to be freed from the wheel of life—an endless cycle of death and rebirth, during which a person endures the suffering of birth and life to purify the titanic element within themselves.

The Orphic teachings were based on sacred writings. Franz Cumont, a world expert on classical period religions, describes Orphism as a religion of salvation based on books. Indeed, the oldest text in Europe, found in the Museum in Thessaloniki, is the Papyrus Devrani, which dates to the end of the 5th century BC. In this scroll, the author takes one of the Orphic hymns and explains that everything is, in fact, an allegory. A hint of this can be seen in the first verse: “You the apprentice close the door.” The author relies on the theories of the pre-Socratic philosopher Anaxagoras, who argued that the stories of the gods represent forces of nature and the act of creation.

According to Eliade, “Papyrus Devrani reveals a new Orphic Theogony that focuses on Zeus. In Orphism, there is a dualism of body and soul close to Platonic dualism, and on the other hand, a series of myths, beliefs, and rules of conduct and initiation that ensure the separation of the ‘Orphic’ from the rest of humans, leading to the separation of the soul from the universe.”

Some scholars argue that Orphism was merely a literary and ideological stream of thought, while others see it as a way of life fulfilled within the framework of spiritual communities, such as the one established by Pythagoras in Crotone in Sicily. The discovery of the connection between the Thracian aristocracy and an advanced and independent Orphism ideology strengthens the understanding that it was a way of life. Orphic life was not just a one-time initiation but a kind of religious way of life practiced as part of a spiritual community.

Aeschylus, the Greek tragedian, had a lost play in which he described the Orphic cult, just as the Greek dramatist Euripides described the cult of Dionysus in the play “The Bacchae.” According to this play, Orpheus would go up every morning to a mountain called Pangaion to bow to the sun, which symbolized for him the possibility of being reborn into the eternal world.

The Orphic doctrine was also recognized and appreciated by the Jews of Alexandria. Aristobulus, a Jewish philosopher from the 2nd century BC, claimed that Orpheus learned from Moses and that there was wisdom common to all mankind. Professor Guy Stroumsa of the Hebrew University expands on the connection between Orphism and Judaism, claiming that it was the first appearance of a modern religion that promotes personal redemption, social life, and morality instead of priestly worship ceremonies and sacrifices in temples.

Orphism can be considered a spiritual school where the mysteries of the heavenly spheres were taught through dance and music, revealing the secret of eternal life and the path to enlightenment. Orpheus’ music brought calm and order to the soul, expressing the structure of the divine worlds. The descent of Orpheus to the underworld symbolizes the entry of divine light and order into the depths of the subconscious, calming the passions and urges to allow a new awareness to be born. Orpheus is the only person who went down to the underworld and returned, meaning he visited the world beyond and can tell us about it. Thus, the School of the Orphic Mysteries taught a way of reaching eternal life, self-perfection, and purity.

Many people studied at the Orphic School. One of the most famous was Pythagoras, who later opened his own spiritual school and community in Crotona, Sicily. One of Pythagoras’ most renowned students was the slave Zalmoxis, who became enlightened and returned to Thrace and Dacia (modern-day Romania) to open a spiritual school of his own.

Zalmoxis

Zalmoxis was a slave of Pythagoras from Thracian or Dacian (Romanian) origin. He learned the secrets of the spiritual path from his master and was initiated into the mysteries of Eleusis in Greece. After he became enlightened, he returned to Thrace (according to Eliade, he returned to Romania—the land of the ancient Dacians) with a distinguished retinue and built a banqueting hall, where he taught the people about the possibility of living forever.

Zalmoxis was revered as one of the gods of the Thracians. In the tomb of the Thracian temple of Aleksandrovo in central Bulgaria, there is a painting of a naked adult man holding a double ax (a symbol of divinity), which is considered to be a representation of Zalmoxis.

According to legend, after a few years of teaching, Zalmoxis asked to be buried alive but prepared an escape tunnel at the bottom of the grave beforehand. After being “dead” for several years, he reappeared and claimed to be resurrected, thus making people believe in his divinity. After several more years, he killed himself once more, but this time for real. He threw himself onto daggers stuck in the ground. However, the faithful disciples who witnessed the first “miraculous resurrection” refused to accept his death and believed he would return from the dead once more, and that in the meantime, he ruled over the world beyond.

Eliade argues that in the regions of Dacian Romania, there existed a kind of religion of Zalmoxis that involved rites of passage and approached monotheism. A priest named Deceneus established the rules of this “sect,” including the avoidance of excessive drinking of wine. Every four years, the Dacians sent a messenger to Zalmoxis, a volunteer who would fall on bayonets to pass into the next world. The cult of Zalmoxis was similar to the Greek and Thracian Mysteries and appears to be a mythical ritual script of death and rebirth, in which a person becomes immortal. A characteristic feature of the cult was hiding in underground caves, followed by an apparition accompanied by a ceremonial celebration, emphasizing the immortalization of the soul and belief in a blissful existence in another world.

According to Strabo, a Roman historian, Zalmoxis learned from Pythagoras the ways of the celestial bodies, astrology, and the art of divination. He went to Egypt, where he studied magic and became a prophet and magician. Zalmoxis became the high priest, close to the king, but eventually retired to a cave on the summit of the holy mountain Kogaionon, “where no one was welcomed except the king and his servants, and later he was considered a god.” He established a divine decree that meat should not be eaten and preached purity and refinement. His worship had a Pythagorean character and was led by hermits and holy men.

Dionysus Sabazios

The Thracians had two spiritual paths: one was that of Orpheus, and the other was of a god named Sabazios, who was later identified with Dionysus. The path of Orpheus is related to ascension, sanctification, and connecting with the higher part of man, while the path of Sabazios chooses first to descend to the instinct and the body, and there discover the impulse of life—the Eros.

According to the stories of the Greeks, the young Dionysus (different from the older Dionysus Zagros) was born to a mortal woman, Princess Semele, and the sky god Zeus. His mother died before he was born, and his father gave him up for adoption to shepherds on Mount Nysa. From a young age, his life was marked by suffering and sorrow. Unaware of his true identity and the source of his powers, he became a violent child, venting his frustrations. As a teenager, his behavior worsened; he would get drunk, become violent, and lose his mind, wandering madly around the world. After experiencing several crises, he decided to embark on a journey to the East to find the source of his restlessness. He traveled all the way to India, where he learned that there was a god within him and ultimately reached enlightenment.

When Dionysus returned from the East, he was already a god, but not an Olympian and distant sky god like Apollo. Instead, he became a compassionate earth god who understood the pain and suffering of humans. The first thing he did was rescue his mother Semele from the underworld. He then married Ariadne, who had wanted to commit suicide after the hero Theseus abandoned her.

Dionysus taught the Greeks the Dionysian mysteries, which included drinking wine, unburdening the yoke, connecting to the human subconscious, and releasing the tangle of passions and desires within. This process led to finding the divine within oneself. Those who did not agree to the strange and new rituals found themselves torn to pieces by the followers of Dionysus—or, allegorically, by the uncontrollable impulses of their own subconscious.

Eliade describes the worship of Dionysus Sabazios as follows: “The ceremony was held at night in the mountains by the light of torches, with rhythmic music, banging on bronze bowls, cymbals, and flutes. The faithful gave shouts of joy and began a stormy and furious circular dance. The women indulged in the wild dances and wore strange, long, and fluttering clothes sewn from fox skins with doe skins on them; they may have even worn horns. They held snakes dedicated to Sabazios and daggers in their hands. When they reached ecstasy, they would seize animals intended for sacrifice, tear them to pieces, and eat the raw meat, thus completing their identification with the god.” According to Eliade, the wild ecstatic experience was an inspiration for a religious vocation, healing, and the gift of divination.

As mentioned earlier, the Thracian Sabazios was identified with Dionysus, and his worship was similar to that of the Bacchae (priestesses of Dionysus who would go out into the forests and mountains). Prophecy was connected with the cult of Dionysus Sabazios, and the Thracian tribe of the Bessi was in charge of its oracle in Perperikon. However, the Thracian Sabazios was also identified as a “rider god,” represented in art by a rider on a horse.

Sabazios the “Rider” is said to have brought religion to Thrace from Phrygia and taught the Thracians to believe in the afterlife and the secrets of the spiritual worlds. Phrygia was an ancient kingdom in what is now Turkey, with its capital called Gordion, located 85 km southwest of Ankara. The Phrygian king, generally referred to as Gordias or Midas, was considered a friend of Dionysus. Sabazios, who according to the Greeks is the embodiment of both Dionysus and Zeus. The spirituality of the Phrygians was advanced and refined, and they were said to have mastered the secrets of magic.

The Phrygians invented music and the two-reed flute that the satyrs played, from which the Bulgarian flute probably evolved. They had a Phoenician script and wore a bonnet, which later appeared as a symbol of the French Revolution and in the seal of the United States Senate. Many of the spiritual traditions of the classical world came from Phrygia, but likely passed through Thrace on their way.

Burial and initiation temples

So far, we have seen that an important element in the spiritual life of the Thracians was the belief in the afterlife, making burial places (temples) of great importance. The tombs of the Thracian aristocracy were built according to the initiation principles of the Orphic way and their understanding of the worlds beyond.

Thousands of tombs of the Thracian aristocracy have been discovered throughout Bulgaria in the last 40 years. These are usually huge mounds surrounded by a circular wall, with the circle symbolizing the sun. The Thracians believed in the holy fire (spiritual light) and the sun. Their traditions included everything related to fire and light, such as star observatories and places of sunrise. Sun worship was associated with horse racing, walking on fire, and wearing masks, all of which have been preserved in Balkan folklore.

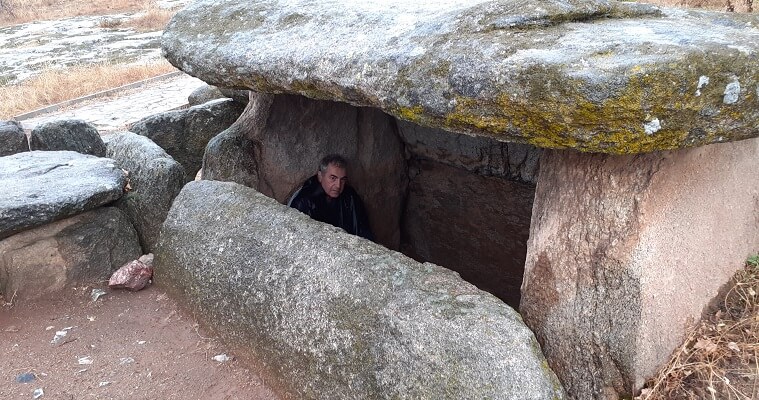

Inside the typical Thracian burial mound structure, there is a corridor leading to an inner room which is a kind of “womb”. In front of the corridor, which usually faces south, there is a platform where the Orphic ceremonies that included music and dance were probably performed. Many times on the back, northern side of the mound, there is a place for the worship of Dionysus (wine press). The entrance corridor leads in most cases to a middle room that resembles a tomb, and after that there is a door or a door frame leading to the inner room which is usually round (resembling a womb), so that a three stage structure is created starting from an entrance of a corridor (sometimes long), continuing into an intermediate room and ending in an inner room.

It is interesting to note that some of the “tombs” were discovered without the remains of human bones inside them, even though they were sealed. Hence, they were not graves in the usual sense of the word, but rather symbolic tombs, probably initiation temples representing the person “buried” in them. The “tombs” vary in size and have sacred architectural proportions and relationships tied to sacred number systems, such as the numbers 6 and 12, or the decimal system. Some of them feature paintings, while others have glyphs and reliefs on columns of various types. The symbols are often geometric, but some take the form of shapes or figures.

The “tombs”—the Thracian temples—are among the most remarkable attractions that Bulgaria has to offer. These “tombs”—temples were built starting from the 5th century BC and, in terms of size and grandeur, they are no less impressive than other monumental structures of the ancient world. Some of them feature large carved stones weighing hundreds of tons, which were brought from far away. It remains unclear how these stones were fitted together so precisely. In some places, the stones are of a special type and are usually connected to each other with iron strips.

Inside the Thracian “tombs”—temples—there is a reverberating sound effect, suggesting they were built for this purpose, further supporting the argument that these were places of initiation. The proportions of the buildings reflect the human body, and it is possible that the size of each “tomb” is related to the person who was initiated there.

According to my understanding of the Orphic way, these were places where a person was “buried” for three days, possibly after consuming hallucinogenic plants, and certainly after participating in ecstatic ceremonies of dance and music held in front of the “tomb,” during which they likely also became intoxicated. The sharp transition from excess to insensibility resulted in the departure of the soul from the body and experiences of astral journeys, similar to the practices of shamans. The individual would symbolically die, experiencing the spiritual worlds for several days. After this period, the door would be opened, and they would be “reborn” into the world, transformed by the experience.

The proportions of the room where the person was “buried” and the type of stone from which it was built helped to intensify the energetic experience. The Orphic conception was that as space echoes sound, it can also echo thoughts and feelings. Different shapes were connected to various cosmic principles, with the sphere or egg symbolizing the cosmic egg from which the world was created. The “tomb” inside the mound symbolized the cosmic womb from which the world was born, replacing the vaginal cave inside the mountain that had previously served this role.

The opening of the “tomb” was often aligned with the sun on a special day of the year so that it would illuminate the interior. Silver plates found in these tombs indicate that sacred marriage ceremonies were performed inside, with Kama Sutra-style depictions that could symbolically awaken the dead.

At the entrance to the “tombs” temples—we usually find a doorway with three different decorations on three staggered lintels. The outer lintel features meanders (windings) of a river symbolizing the River Styx. The middle frame displays an egg symbolizing rebirth, while the inner frame is adorned with pearls that may symbolize the moon, the treasure, and the eternity they were seeking.

Inside the inner room, gifts related to a person’s life in this world and the next were placed. This is why we find gold and silver treasures in the tombs, including masks, trophies, helmets, symbolic shields, horse harnesses (a horse is considered an animal that knows the way to the world of the dead), and more. Objects related to the head, such as helmets or crowns, were placed in the north, while objects related to the legs, such as knee pads, were placed in the south. This arrangement indicates that the temple was designed with reference to the human body.

Sometimes, the deceased was burned or torn to pieces, with the large bones that survived the fire placed in urns. These urns were then positioned in six locations around the tumulus—the burial temple. This practice might explain the absence of skeletons in the inner chambers. The remains of a person’s ashes recalled the myth of Dionysus Zagreus and the creation of man from the ashes of the Titans. In this context, the inner chamber of the empty “tomb” symbolized the process of purifying the divine element in man from the titanic ashes, leading to the possibility of eternal life.

Various researchers have tried to explain the meaning of the objects found in the “tombs” temples—and the principles of their sacred architecture. Some Thracologists concluded that these structures embodied a form of mystical numerology, similar to the teachings of Pythagoras. It should be noted that the Thracians were concerned with the worlds of energy and the afterlife. In Dunov’s “White Brotherhood,” it is claimed that the Thracians believed in ten different energies that make up the world, similar to the concept in Kabbalah. This belief is also shared by Georgi Kitov, a leading archaeologist on Thracian sites.

In addition to the importance of numbers, proportions, and spaces in the Thracian tomb temples, colors also held significant meaning: blue symbolized the sky, both physical and spiritual; black symbolized the underworld; and red symbolized the earthly world. When these three colors are mixed, they create the eternal color of dark purple (Orphninus). These three colors frequently appear in the decorations of the Thracian tomb temples throughout Bulgaria.

In the “tombs,” many small figurines of human images associated with the Orphic cult were discovered, as well as representations of geometric bodies. Triangles represented fire (according to the Pythagoreans), cubes represented the earth, and spheres represented the cosmic egg from which the universe was created.

In many “graves,” a mirror is found, one of the sacred objects of Thracian Orphism. According to the Orphic myth, Dionysus Zagreus was scattered into many parts while looking into a mirror. This reflects the perception that there is a hidden reality, which is a reflection of the chaotic physical reality, and within this hidden reality, there is a divine order.

Thracian kingdoms

As mentioned earlier, Indo-European peoples arrived in the Balkans, probably in the 3rd millennium BC. They mixed with the local population and created the ancient “proto-Thracian” tribes and kingdoms. We don’t know much about this period.

In the 2nd millennium BC, the Mycenaean culture developed in Greece, the Minoan culture in Crete, and the Thracians appeared as part of the ancient world, allied with the city of Troy. The new Greek tribes (the Dorians and the Greeks) went to war with the existing order and the old forces, as reflected in the stories about the Trojan War, which was essentially a civil war. The Thracians supported the Trojan side, indicating that they were part of the ancient golden order of the Bronze Age, which lost its hegemony to the Greek warriors of the Iron Age.

The Trojan War dates back to the 12th-13th century BC. In the Iliad and the Odyssey, various Thracian tribes such as the Kikones and the Paiones are mentioned as fighting against the Greek heroes and are praised for their courage. The most famous Thracian leader from this time is the legendary King Rhesus, who was murdered in his sleep but was resurrected to immortality by his mother, one of the Muses. This story (mentioned in the Iliade) is the subject of one of Euripides’ tragedies. Other important figures include Eumolpus, who was one of the six kings that founded the Greek mystery tradition of Eleusis and may have brought it from Thrace, and Diomedes of Thrace, to whom Hercules was sent to perform his eighth labor because he had man-eating horses.

In other words, Greek mythology is full of stories about legendary Thracian kings, the most famous of whom is undoubtedly Orpheus. These legends likely reflect the existence of some type of loose Thracian kingdoms or tribal confederations that stretched from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and the Dardanelles north to Romania and Serbia.

In the 8th century BC, Greek and Phoenician settlements began to be established on the shores of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, including in Thrace. Cities—polis—such as Amphipolis, Avdra, and Maronia (today in northeastern Greece) were built. Thrace became a meeting point between East and West, North and South, and during the archaic period, between the Phoenicians and the emerging Greek cities. This interaction led to cultural fertilization and allowed the transfer of the Phoenician alphabet and writing system to Greece. In the classical period (5th century BC), the Spartans and Athenians fought for control over the Thracian coastal colonies and islands, particularly over the rich gold and silver mines on Mount Pangaion.

At that time, the Thracians formed into several unions or kingdoms. The Bessi tribe in the Rhodope Mountains formed one kind of union, they were considered a kind of Thracian sect of priests who engaged in prophecy and were connected to the center of the god Dionysus in Perperikon. The Bessi lived in the Rhodope, but also in the central part of the Maritza River bed and in the Balkan Mountains. In the 6th century BC, they developed military capabilities and began to establish a sort of independent kingdom in the area of the Rhodope and Rila Mountains. They resisted the Persian occupation of Thrace, and centuries later, they also resisted the Roman occupation.

The Odrysian tribes lived in the lower plain of the Maritza River, and their ancient capital was probably Edirne in Turkey. After the Persians’ loss to the Greeks, a union of Thracian tribes began to form around this center, controlling most of the territory of today’s Bulgaria and parts of the neighbouring countries. It was a kingdom with no fixed capital or urban centers, ruled by a spiritual aristocracy that built the wondrous tomb temples. Over time, the kingdom’s center shifted to the Starosel region in the Sredna Gora Mountains and the Rose Valley at the foot of the Balkan Mountains. One of the last kings of the kingdom built a permanent capital near the city of Kazanlak, named after him—Seuthopolis. During this time, the Thracians adopted the Greek script and some of their cultural customs.

North of the Balkan Mountains, there were two important and powerful tribal unions that remained independent for some time. In the northeast and on both sides of the Danube were the Getae, whom the Greeks considered noble among the Thracians and whom the Romanians consider part of their heritage. In the northwest were the Triballi tribes—daring warriors who lived in the territories of eastern Serbia, northern Macedonia, and northwestern Bulgaria. The Triballi were influenced by the Celts and the Illyrians.

The end of the Thracian period

In the 4th century BC, a king named Philip came to power in Macedonia. He grew up in Thebes, which was the leading city of Greece at the time, and came to admire Greek culture. He learned its ways and brought them back to his home country. Philip established cities, organized an efficient system of government, reformed the army, and taught it Greek methods of fighting, such as the phalanx. He also educated the youth in the spirit of Greek philosophy, freedom, and open mind. To this end, he brought to his palace in Vergina the best pedagogues, chief among them the philosopher Aristotle, who was the personal tutor of his son, Alexander the Great, for several years starting from the age of thirteen.

Philip succeeded in implementing the Greek system on a large scale, creating a sort of first modern state with a road network, large irrigation systems (canals), and silver and gold mines that brought significant income to the state treasury. The land of Macedonia is fertile and able to support a large population compared to the arid lands of Greece. Philip managed to reach a critical mass of cities, people, money, and military power. He founded a standing army and added the Thessalian cavalry to the classical Greek combat system of the phalanx. With the help of this new army, he conquered Thrace, all of Greece, and large parts of the Balkans by the end of the 4th century BC.

The Macedonian occupation meant that many sacred Thracian sites in the mountains were hidden or abandoned, leading to the partial forgetting of the Thracian spiritual tradition, with the remainder going underground. Like many ancient peoples before them, the Thracians chose to hide their spiritual sacred places and seal them to prevent visibility to robbers and desecration by invaders. During this period, a large number of tomb temples in the Valley of the Kings and the nearby mountains were covered with earth and sealed.

From this time onwards, Thrace (Bulgaria) became part of the Hellenic-Roman world. Philip established cities throughout the country, the first and largest of which was Plovdiv, named after him—Philipopolis. He continued with the sanctification of some Thracian sites, especially the temple of Dionysus Sabazios in Perperikon.

It should be remembered in the context of Thracian spirituality that Alexander the Great’s mother, Olympias, met his father Philip at the mystery center of the Thracians on the island of Samothrace. They were ritually consecrated as a couple, and thus the conception that summoned Alexander’s spirit into the world took place during the initiation rites of Samothrace.

Alexander’s journey to the East was not only a journey of conquest but also a quest for wisdom, meaning, and an attempt to merge all cultures, religions, and spiritual paths into a common human quest. His campaign of conquest was probably the most influential in history and marked the most significant meeting between the East and the West. When Alexander conquered the East, Eastern spiritual elements such as the belief in the Redeemer (Soter) merged with Greek religion and spirituality. This led to a blend of Greek polis culture with Macedonian, Thracian, and Eastern cultural elements, known as Hellenism.

Following the conquests of Philip and Alexander, Thrace (Bulgaria) remained under Hellenic rule and influence for nearly 200 years, until the Romans arrived, defeated the Macedonian phalanx at the Battle of Pydna, and established their rule over this part of the world as well.

Bibliography

Eliade, M. (2014). A history of religious ideas volume 1: From the Stone age to the Eleusinian mysteries (Vol. 1). University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, M. (2011). History of Religious Ideas, Volume 2: From Gautama Buddha to the Triumph of Christianity. University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, M. (2022). Patterns in comparative religion. U of Nebraska Press.

Fol, A. (2007). Orphica Magica I. ORPHEUS. Journal of Indo-European and Thracian Studies, (17), 15-109.

Fol, A., & Marazov, I. (1977). Thrace & the Thracians. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Fol, A. (1991). The Thracian Dionysos. Book One: Zagreus.

Cumont F. After Life in Roman Paganism : Lectures Deliverd at Yale University on the Silliman Foundation. Dover; 1959.

Kitov, G. (1996). The Thracian Valley of the kings in the region of Kazanluk. Balkan studies, 37(1), 5-34.

Maglova, P., & Stoev, A. (2015). Thracian sanctuaries. Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy, 1385.

West, M. L. (1983). The orphic poems. Oxford Univ Pr.