This is a rudimentary translation of articles from my book “Goddess Culture in Israel“. While it is far from ideal, it serves a purpose given the significance of the topic and the distinctiveness of the information contained. I have chosen to publish it in its current state, with the hope that a more refined translation will be available in the future.

Construction of Houses

With the dawn of agriculture, a monumental shift occurred as individuals transitioned from residing in caves to establishing permanent abodes in villages. Concurrently, the concept of sacred space transitioned from the cave to the domicile.

Poetically speaking, if caves were once regarded as the womb of Mother Earth, then during the Neolithic era, dominated by the development of agriculture and the worship of the Goddess, humanity began to exit this womb. Consequently, they found themselves in need of creating a new locus for habitation and spiritual connection, essentially a temple of life. However, this transition carries a profounder significance. Whereas tribes once roamed or dwelled in caves as a collective of 20-25 people, functioning as an extended family, the inaugural homes constructed represented a sort of chamber (originally circular, later evolving into rectangular shapes) designed to accommodate a single family unit—possibly comprising a mother, a father, and their children. These homes were erected within villages that housed several hundred individuals.

Rappenglück suggests that in the development of society and the organization of the human world, it was essential to establish restrictions, separations, divisions, and selective passages between realms (membranes). This structuring allowed for the concentration of efforts and resources, thus defining social and human life. As a result, various boundaries and enclosures became crucial for the growth of humanity and its societies. Constructing a house served as such an enclosure, delineating the safe from the vulnerable, the intimate from the remote, the civilized from the untamed, the realm of the living from that of the dead, and the secular from the sacred. In contrast to the naturally occurring cave, the house was an entirely human creation. While we continue to inhabit houses today, in the culture of the Goddess, the house held a deeper significance, as their world was imbued with spirits and perceived as mysterious and magnificent.

The earliest houses in the world were likely constructed in what is now Israel. Tamar Noy has noted that in these early permanent settlements, a deep and particular connection formed with one’s place of residence, extending to a broader relationship with the living environment. The home, alongside the activities that regularly occurred within its walls and in its vicinity, was central to family life. This emphasizes the significance and unique characteristics of dwellings during the Neolithic period, known as the era of Goddess culture.

Rappenglück points out that the walls of a house were viewed by ancient peoples as a selective membrane, allowing the flow of energy and matter. These walls, featuring both an inner and an outer side, served to separate and connect the inside with the outside, thereby also linking different worlds. This is the reason magical paintings are often found on them. The openings in these walls enabled transitions between realities, highlighting the sacred importance of doors and gates. They were perceived as horizontal portals to the vertical, three-dimensional reality of the house, representing it as a world axis.

Houses were often viewed as living entities, akin to a human body, with various parts corresponding to different areas of the dwelling, such as in the Vedic tradition of Sthapatya Veda (architecture) in India. Furthermore, the entire ecology was seen as a living organism, comprised of various components imbued with both matter and spirit. The interplay of light and shadow introduced an additional dimension to the architecture, where the ingress of light through openings in the roof or walls would illuminate different sections of the house, serving as a marker for the passage of time.

The house evolved into a nexus of life, culture, family, and the union of male and female, fostering growth, sanctification, and prayer, as well as serving as a sanctuary for sleep, during which individuals transitioned to another dimension. Within Goddess culture, the house also embodied the cycles of birth and death, mirroring the cosmic container where life originates and can transition back from the temporal to the eternal. This reverence for the cycle of life and death is reflected in the practice of burying skeletons beneath the house floors[1], integrating the spirits of ancestors directly into the fabric of the home. These spirits, particularly those of mothers, became an integral part of the household, offering guidance and support to its inhabitants.

Eliade posits that fundamentally, humans are in pursuit of a central locus—a place of rebirth, a return to a home that transcends the immediate, the mundane, and the temporal. This quest is driven by a desire to connect with the Sacred, hence every dwelling and place of habitation is structured around a mythical center, fostering a sense of sacred belonging. In this perspective, the house becomes a divine dwelling, the universe’s core. It embodies an “Imago Mundi,” containing within it an “Axis Mundi,” serving as a microcosm of the world and a pivotal point connecting the earthly to the divine.

Rappengluck suggests that human perception of the environment is inherently topocentric, necessitating a central point of observation. He argues that the moment humans stood upright, they established a center that divided space according to cardinal directions, thus creating a vertical connection between the heavens and the earth. This innate human inclination to establish a central point in the world is an anthropological motif, stemming from the adoption of an upright position. The resulting sense of balance forms the initial axis mundi, a conceptual line that connects the nadir (the point on the ground where one stands) with the zenith (a line extending from the center of the Earth through the body and up to the sky). When humans began constructing dwellings, this world axis shifted to reside within these structures, often symbolized by a pillar or a central feature such as a hearth. Essentially, humans started to identify their bodies and their being with the space they occupied.

In the early stages of permanent settlement, humans predominantly used stone for construction and resided in or near mountainous and hilly regions. Approximately 9,000 years ago, they descended from these elevations to settle in the valleys, a transition made possible by the introduction of mud bricks. Humans devised a method to create clay by mixing earth with straw, which was then dried either in the sun or by fire, resulting in bricks used for building their homes. This new material led to a shift in the architectural design of houses to a rectangular shape. This transformation occurred in tandem with pivotal developments such as the advent of agriculture, the domestication of sheep and goats, and the eventual move away from hunting and gathering as the primary means of sustenance. According to archaeological perspectives, this era is referred to as the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic B period, dating from 8,500 to 7,000 BC.

The newly constructed rectangular mud brick houses were significantly larger, doubling the size of the earlier round stone and straw dwellings, and featured plaster floors, possibly housing multiple families. These developments are evident in sites such as Yiftahel in the Beit Netufa Valley and Byada, near Petra, showcasing this architectural shift.

Stone houses were simultaneously being refined. In the region around Transjordan, particularly in a site known as Basta near Petra, sophisticated dwellings have been unearthed. These houses, constructed from stone slabs, have been preserved up to a height of 4 meters and feature windows, doors, plaster floors, and even a second story, giving the impression that they could have been built in modern times. It appears that the Goddess culture in the highlands of Gilead and Moab was more advanced than that in the valleys and mountains of Israel during the same period. This distinction might be reflected in the Bible, where areas of Transjordan are associated with the dwelling places of magicians and giants.

Establishment of Villages

The advent of agriculture and the shift towards permanent housing led to a significant transformation in social living patterns: the transition to village life. During the era of hunter-gatherers, the social unit was typically a tribe of 20-25 individuals. This dynamic evolved into a nuclear family residing in a home, within a village populated by hundreds of people. Communities now lived in villages, ranging in size from a few dozen to several thousand inhabitants. This shift necessitated a means to unify society, a role that was filled by the worship of the Goddess.

The significance of transitioning to life in villages—a permanent setting where a community could forge its own world—cannot be overstated. This monumental shift raises numerous questions: How were the earliest villages structured? Who governed them? Was there an overarching blueprint guiding their layout? How was the allocation of essential resources, like water, decided? What delineated public spaces from private ones? Were the dwellings constructed in close proximity, perhaps even abutting one another as seen in Çatalhöyük, Turkey, or were they spaced apart? These inquiries delve into the foundational aspects of early communal living and the organizational challenges faced by these nascent societies.

In Çatalhöyük, the houses were part of a connected aggregate, creating a unique urban fabric where movement from one dwelling to another occurred across and atop shared roofs, which served as both a means of access and potentially public spaces. Entrances to the homes were through openings in the roofs. In such a configuration, the concept of village life meant that the lives of its inhabitants were closely intertwined; sounds and conversations could easily travel through the walls, and maintenance and construction activities were communal efforts. This kind of architectural and social organization led to a social structure distinct from that found in villages where houses are separate and isolated from one another, reflecting how the physical layout of a community can deeply influence its social dynamics and interpersonal relationships.

Jericho is recognized as the world’s first village, and intriguingly, it featured not only private residences but also significant public structures, such as a prominent tower. This indicates there was a collective effort within the community towards public projects, showcasing a communal investment of time and resources. Such endeavors suggest that the early inhabitants of Jericho perceived their settlement not merely as a collection of individual homes but as a living entity, akin to an extended family to which all members belonged. This communal spirit underscores the idea that early villages functioned as integrated, cohesive communities with a strong sense of unity and shared purpose.

With the advent of the agricultural revolution, the concept of the residential home acquired cosmic symbolism and was sanctified, a process that likely extended to the village as a whole. The village thus became an “Imago Mundi,” or image of the world, containing elements that mirrored the cosmogony of the universe. Typically, in every sizable village, there was a temple or worship site acting as the “Axis Mundi,” or the world’s center. Close to this spiritual heart, one would find storage for agricultural produce and craft workshops dedicated to weaving, spinning, and pottery. The level of cooperation among the village’s women surpassed what is common today, with some villages practicing communal cooking rather than individual household preparation. Similarly, crafts like basket weaving and pottery were collectively undertaken in communal workshops that also served as temples to the Goddess, illustrating a deeply integrated social and religious life that emphasized community and shared responsibilities.

In certain villages, features such as wells, communal silos, and orderly streets aligned with the cardinal directions were discovered (for instance, streets paved with plaster at Shaar Hagolan), suggesting two significant insights. Firstly, there was a level of advanced societal organization responsible for determining the layout of streets and placement of houses within the village. Secondly, this organization was influenced by a religious framework that underscored the significance of directional orientation. It seems likely that the planning of these villages was overseen by a council comprising women priests or tribal representatives, with decisions being reached through consensus, a common practice in matriarchal societies. This points to a sophisticated and deliberate integration of spiritual beliefs with the practical aspects of urban planning, reflecting a deep cultural coherence in these early communities.

The worship of Goddesses often included dancing, and living in villages facilitated the formation of large dance circles, enriched by music and ecstatic drumming, under the leadership of priestesses and shamans of both genders. These celebrations, designed to align with the agricultural calendar and significant dates, became an integral component of village life. Through these rituals, the Goddess’s presence was invoked to mark crucial seasonal transitions and communal events, embedding these spiritual practices within the fabric of daily existence and reinforcing the community’s connection to the cycles of nature and the divine.

The question of social stratification within these early villages—whether there were marked differences in property and status among the inhabitants—is complex, yet the evidence suggests that significant stratification did not occur, at least not in a discernible manner. Archaeological findings indicate a general uniformity among the houses in a village, with no substantial disparities observed in the burial practices and grave goods of the residents. Claire Epstein, a prominent archaeologist specializing in the study of village life during the late Goddess culture era, made significant contributions to this field through her excavation of dozens of villages from the Chalcolithic period in the Golan. Her discoveries underscored this trend of homogeneity, revealing that all houses within these communities were identical, suggesting a level of egalitarianism not commonly associated with later historical periods.

However, this narrative is not without its nuances. In certain locations, the emergence of larger houses with expansive courtyards has been observed, leading some to speculate on the beginnings of social stratification and differentiation. Even if this interpretation holds, it arguably does not diminish the era’s prevailing spirit. Notably, there is no archaeological evidence of kings or rulers, nor were there urban centers or fortified villages, suggesting a society without marked hierarchies or centralized governance, maintaining a communal and egalitarian ethos despite the potential for emerging disparities [3].

For millennia, spanning from the advent of agriculture to the rise of cities, individuals resided in flourishing villages where cooperation was the norm. They willingly contributed to both society and the communal domain, living in a state of harmony and peace. Guided by the Goddess, humans embraced values of awareness, responsibility, and consideration. This ethos was manifested in a dual fashion: on one hand, each person cultivated their own food, ensuring independence from the sustenance of others, while on the other, they supported their neighbors, friends, and fellow villagers, fostering a community of mutual aid and solidarity.

Building of Sanctuaries

The foundational principle of Goddess culture posited that every location and every living entity was sacred, yet it also recognized specific sites where crucial processes such as fertilization, procreation, and transitions between dimensions took place. This suggests that the understanding of a sacred site within Goddess culture integrated seemingly contradictory perspectives. In the temples dedicated to this culture, there was a distinction made for the sacred space, yet simultaneously, these sacred places were deeply intertwined with daily life, craftsmanship, life cycles, and the natural environment. This duality reflects a holistic view of the sacred, seamlessly merging the spiritual with the mundane.

The Goddess culture’s reverence for all forms of life as sacred and its view of the world as a cohesive, nurturing, and interconnected web sometimes blurs the lines between what might be termed an “ordinary house” and a temple. Given that every dwelling was deemed sacred and likely incorporated elements of Goddess worship—such as burials beneath the floor, spaces for offerings, and urns adorned with symbols of the Goddess—it’s challenging to distinguish between domestic and religious spaces. For instance, at Shaar Hagolan, a significant house was uncovered containing around seventy figurines of the Goddess, prompting debate over whether it served as a large family residence or a temple.

Globally, there exist examples of temples embedded within residential structures where domestic tasks were performed, as well as spaces that seemed to combine workshops with religious functions. In Goddess culture, activities like wheat grinding, baking, weaving, and pottery were regarded as sacred endeavors. Maria Gimbutas highlighted temples to Goddesses that were adjacent to workshops, suggesting a symbiosis between the spiritual and the practical, such as a temple on the first floor and a pottery workshop on the second. This architectural integration prompts the question of whether two-story houses in the ancient Goddess culture across Trans Jordan might have served dual roles as both workshop/residence and temple, reflecting the culture’s holistic integration of the sacred into every aspect of daily life.

The Goddess culture revered nature as the domain of Mother Earth, manifesting through caves, protruding rocks, water springs, and various unique locations. This reverence wove a network of sacred sites across the Earth, with certain spots becoming focal points for communal gatherings. On special days throughout the year, villagers would assemble at these sacred places to partake in religious ceremonies, underscoring the deep connection between the community, the natural world, and the spiritual realm. This network of sacred sites facilitated a communal spirituality that was both grounded in the natural landscape and integral to the cultural identity and rituals of the people.

The worship of the Goddess unfolded across various levels of society, encompassing the family unit, the village community, and broader regional affiliations. The journey to regional centers for collective worship often began with pilgrimages to distinctive natural sites, which in time evolved into the Megalithic sites, complexes, and regional temples, such as Gilat in the Negev. These significant gatherings, whether they were weekly, monthly, or aligned with special community events, featured ceremonies that integrated dance, music, trance, healing, and rites of passage and initiation. The necessity for a dedicated space for these village assemblies gave rise to the development of local temples, serving as focal points for communal spiritual activities and reinforcing the societal fabric of Goddess worship through shared rituals.

In the final stages of the Goddess culture, specifically during the Chalcolithic period, we observe the emergence of distinct temples that stood apart from the realm of everyday life. A prominent example of such a temple is found in Ein Gedi, though there are numerous others, including the Ramat Saharonim temples in the Negev. These temples are known to us through models discovered at the temple sites themselves, and archaeological excavations. The advent of clay use facilitated the creation of detailed models of houses and temples, offering insights into their structure and function. Maria Gimbutas describes a temple model from the Balkans featuring two rooms: one housing a large figurine of the Goddess and the other containing seven smaller Goddess figurines in various forms. She interprets this as indicative of a temple led by a high priestess assisted by seven helpers.

Connection to the Earth

The Goddess, who presided over the cycles of life and death, was synonymous with Mother Earth. During the era of Goddess worship, the Earth itself was viewed as a manifestation of the Sacred, with life emerging from its womb and death marking a return to its embrace. This perception sanctified the deceased, allowing for their rebirth. This theme resonates in later mythologies, such as those of Sumer and Egypt, where the Earth is often equated with the ground emerging from primordial waters. In these narratives, water represents the dormant energies of the cosmos, while the ground symbolizes the Earth. Life begins only when the ground surfaces from these waters, signifying the moment when form can take shape and existence can flourish.

Eliade eloquently states, “Water is at the beginning and at the end of every cosmic event. Land (earth) is at the beginning and at the end of life… Every form is born from it, lives and returns to it when the life for which it was destined is finished and completed, and it returns to it in order to be reborn.” In this view, the Goddess is intimately connected with Mother Earth, embodying the fertile ground from which life springs and to which it ultimately returns. Yet, her association extends beyond the earth to encompass water, the fundamental element that permeates the cycles of the moon and life itself. The multifaceted nature of the Goddess, manifesting in various forms, aligns with her dominion over life’s vast tapestry and cycles. This diversity in representation reflects her comprehensive role in overseeing the continuum of existence, from birth through life, death, and rebirth, mirroring the endless ebb and flow of cosmic and terrestrial rhythms.

The ground serves as the final resting place for humans upon death, and thus, the blessing of the deceased is deemed necessary for the success of crops emerging from the earth. In the era of Goddess worship, connection with the ground offered a means to engage with the continuum of time and the spirits of ancestors, integrating oneself into the universe’s fabric. Eliade articulates this relationship, stating, “Between the earth (ground) and the organic forms it created, there is a bond of sympathetic magic; everything together constitutes one system, one whole. The invisible threads that bind vegetation, animals, and humans in a certain area to the earth that created and nourishes them all are woven from the pulsating life found in both the mother and in creation. The solidarity existing between the earth and humans, vegetation, and animals stems from life, the same element present in all kingdoms. Their unity is biological. When one mode of this life’s existence is harmed by a crime against life, all other modes suffer as well due to the organic solidarity between them.”

Given the sanctity of the ground, those deemed sinners were not allowed burial within it. The spilling of criminal blood upon the earth was believed to defile it, resonating with the biblical phrase “the sound of your brother’s blood cries out to me from the earth,” and leading to infertility. This concept is mirrored in the myth of Demeter and Persephone, where the earth’s barrenness persists until cosmic order is reinstated. Consequently, the cults venerating the earth Goddess were intrinsically linked with renewing the ethical pact between humanity and the Great Mother. Within this framework, the maintenance of justice and the establishment of a harmonious society were viewed as prerequisites for ensuring the earth’s fertility, epitomizing the ideals of Goddess culture.

Mother Earth embodies the essence of the Supreme Goddess, serving as a cohesive force that binds the universe and existence, touching the fringes of ancient monotheism. She was the steward of life and death, the overseer of procreation and crafts, and the guardian of flora and fauna, abstract thought, art, and the realm of the deceased. This multifaceted deity represented a singular, supreme organizing principle, encapsulating the cycles of nature, the passage of time, and every stage of human life within her domain. Over time, the comprehensive nature of the Great Goddess fragmented into various deities, each presiding over specific aspects of existence. Eliade acknowledges the unique status of Mother Earth among divinities for her near-universal reverence: “only a few divinities enjoyed, like the mother earth, the right to become universal”, However, he notes that: “The hierogamy (Sacred marriage) with the sky and the appearance of the agrarian divinities prevented the ascension of mother earth to the status of a supreme, if not truly singular, deity.”

The harmony of the universe was reflected in the reciprocal relationship between humanity and the earth: the fertility of women impacted the fecundity of fields, while bountiful harvests aided in conception. Furthermore, the departed contributed to the land’s fertility, which facilitated their spiritual renewal and return to life. Therefore, when humans conducted rituals and practiced magic to support natural and agricultural cycles, they were essentially aiding themselves. A profound solidarity existed among various life forms and actions, with ceremonies and worship enhancing natural processes. Although these processes would occur naturally, human rituals infused them with sympathetic magical power, ensuring their integration into the rhythms of human life and existence.

The recognition of the sanctity of the land fostered the perception of the Earth’s surface as a vast organism, akin to a human body on one level, or as a microcosm reflecting the cosmos on another. Consequently, various regions within the Land of Israel (or in other countries like Egypt) were correlated with distinct anatomical or cosmic components, such as parts of the human body or celestial constellations [4]. This conceptual framework was underpinned by the Goddess culture’s holistic view of the universe as an interconnected fabric, further emphasizing the intrinsic unity and interdependence of all existence.

The Earth was perceived as imbued with a radiant soul by adherents of the Goddess culture. Priestesses of this culture exhibited a heightened sensitivity to nature’s nuances, including the emanations emanating from the land. They discerned that each location possessed unique energies, with particular places exhibiting the strongest and most refined vibrations. These sites were consecrated after careful selection and then refined, shaped, and designed to amplify the land’s energies in a manner conducive to blessing crops, animals, and humans. This process involved various earthworks, the arrangement and manipulation of natural caves and rocks, the erection of massive stones in specific configurations, leading to the creation of what are known as megalithic complexes. Over time, temples were constructed at these chosen sites. In addition to stones, trees, bonfires, fabrics, colors, crystals, and bones were utilized, although many of these materials have not survived the passage of time.

Rappengluck observed that specific locations on Earth were believed to possess influences that could be either advantageous or detrimental at particular times. These sites served as points of convergence for opposites, representing the meeting of different worlds that complemented and balanced each other. Enclosures and sacred spaces were regarded as areas where communication with cosmic forces was feasible [5].

Importance of Water

The Goddess culture revered water as a manifestation of the divine, particularly in the form of water sources such as springs, streams, or lakes. Remarkably, this culture pioneered the practice of digging wells, initially within a religious context. The ancients recognized the profound significance of water, which descends from the sky to nourish the earth, viewing it not merely as a natural occurrence but as a divine miracle unfolding annually. This miracle was perceived as twofold: precipitation descending from the heavens and water miraculously emerging from the earth, even from rocks. Despite the absence of rainfall in the Land of Israel for several months each year, the region abounds with water springs, flowing streams, and bodies of water.

Water played a pivotal role in the lives of people within Goddess cultures. It was revered as the ultimate source of life, an expansive and undefined medium embodying the all-encompassing feminine essence—a realm unrestricted by clear definitions, but rather rooted in intuition and profound, unconscious sentiments. The primordial waters were perceived as a chaotic yet vital life force, facilitating the processes of creation and birth. This cosmological concept extended into the physical realm, symbolized by the womb—a cosmic egg—wherein the unborn child is cradled, submerged in the nurturing embrace of water.

It could be argued that the sky represented the boundless potential of creation, while the earth or rocks symbolized the initial solidification, delineation, and differentiation inherent in the creation process. Water, on the other hand, was perceived as a substance harboring the seeds of life, intricately linked to the lunar and fertility cycles [6].

The full moon exerted a profound influence on the ebb and flow of the sea, a connection that the ancients keenly observed. They recognized the mystical bond between the moon and water, evident not only in the tides but also in the ethereal mists that enveloped the earth—composed of water vapor—and the clouds that proliferated during the full moon, bestowing rain upon the earth. While the ancients may not have comprehended all the intricacies of the water cycle, they understood that water, in conjunction with the moon, formed a dynamic fabric essential for sustaining, facilitating, and nurturing life.

The Goddess held sway over the sources of water, a fact reflected in the symbols adorning her artistic representations. These included parallel or undulating lines featured on her figurines and on urns holding the agricultural bounty under her domain. Notable water symbols included the V shape, emblematic of flowing water [7], and a web motif, signifying the intricate and unconscious interconnection of water and the moon, linking all existence [8]. Each of these symbols served to convey various facets of the Goddess’s influence and domain.

Water possessed a remarkable attribute: its capacity to serve as a reflective surface, akin to a mirror, rendering it associated with prophecy. In essence, water was believed to possess metaphysical properties. Thus, in ancient times, black bowls were often filled with water, and witches and prophetesses would gaze into them, awaiting visions and images to manifest in their minds. This practice likely finds its origins in artifacts such as the broken black basalt bowl unearthed in the Witch’s Cave in Nahal Hilazon, dating back as far as 15,000 years ago.

Water possesses the inherent ability to cleanse, encompass, decompose, and purify, serving as a universal solvent that washes away impurities on all levels. As a result, water became integral to purification rituals. Interestingly, the ritual of baptism traces its origins back to the era of the Goddesses, and possibly even earlier. Figurines representing the Goddesses, along with sacred stones—particularly those symbolizing the Goddess—were ritually bathed in holy water, thereby rejuvenating their potency and ensuring the fertility of the fields. Essentially, water was imbued with a magical quality, capable of affecting those immersed in it, and baptism was perceived as a means of transitioning from one realm to another.

Water possesses yet another miraculous quality: its capacity to change states. It can freeze and transform into ice, or heat up and become steam. This unique characteristic sets water apart from all other substances in nature, contributing to its sacredness. However, above all, it is water’s life-giving property that renders it holy. The necessity of water for human survival—to drink and sustain life—and its essential role in nurturing plant growth underscore its sacred significance. Indeed, all life depends on water, reinforcing its profound sanctity.

The ancients viewed water as possessing memory—a receptacle capable of retaining energy that not only influences, but is also influenced. They would gather special types of water, such as dew water during solstices or the last rainwater of the year in May, employing it for healing purposes and in religious ceremonies. Moreover, they constructed megalithic sites in close proximity to water sources, believing in the reciprocal interaction between water and stone. For instance, Rujum al Hiri stands near the flowing stream of Nahal Daliot. Additionally, sacred basins were integral features of ancient temples.

The ancients revered springs, which embodied a fusion of a cave, water, and the miraculous emergence of life from the inert. This water, sourced from the depths of Mother Earth, was deemed a gift to humanity—its provision stable and life-sustaining. People drank, bathed in, cooked with, and irrigated their animals and plants with this water. Essential to every settlement, a spring or permanent water source was considered sacred—a cosmic axis connecting the plains. Humans believed divine beings resided within these springs, such as Anki, the Sumerian god of the depths, or the nymphs of Greek mythology. Some springs were destinations for pilgrimage, endowed with healing properties. Drinking from and bathing in these waters brought solace to the sick and fertility to women.

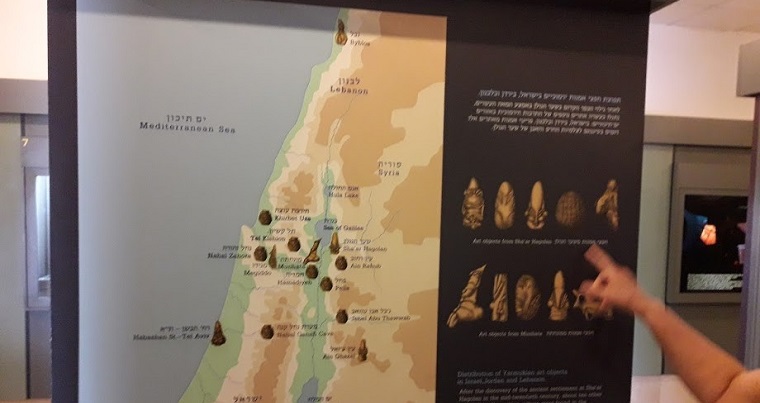

Pools and water reservoirs held sacred significance during the era of the Goddesses, Lakes as well. The Sea of Galilee was a pivotal religious hub during this period, with a significant settlement, Shaar Hagolan, established nearby, lending its name to an entire culture. The unique contours of the Sea of Galilee were intertwined with female symbolism, leading to the construction of villages and monumental structures along its shores, possibly including temples dedicated to birth (refer to the “Sea of Galilee” chapter).

The rivers were perceived as integral parts of the Goddess’s body, akin to the strands of Shiva’s hair in ancient Hindu beliefs. The hydrological network mirrored the energetic meridians of Mother Earth. The origins of rivers were deemed sacred, with the sources of the Jordan River at the base of Mount Hermon holding particular significance in Israel. The flow of rivers was likened to the journey of life, viewed as energetic arteries connecting disparate locations on Earth, akin to the Milky Way in the sky, the source of creation.

The association of water with the womb was symbolized through the sanctification of wells, evident in the discovery of two ancient ritual wells in Israel. One, submerged in Atlit Yam, dates back to 9,000 years ago, while the other, near the Yarmuch River at Shaar Hagolan, is from 8,000 years ago. Interestingly, these wells were situated in locations where their practical necessity was questionable, yet they were constructed with significant investment and using special stones for religious purposes.

Later cultures that inherited the traditions of the Goddess culture continued to sanctify wells. Among them were the Celts, who excavated deep pits in the ground, typically ranging from 2 to 3 meters in depth, although some reached depths of up to 13 meters. These were ceremonial wells where offerings, sacrifices, ashes of the deceased (both human and animal), urns, Sacred objects, and occasionally treasures of gold and silver were placed in ceremonial bowls. A symbolic tree was often positioned at the center of the Celtic well, likely representing the cosmic tree. These Sacred wells served as points of connection between humanity, the earth, the underworld, and the realms beyond, facilitating the fertilization of the earth through their spiritual significance.

The wells from the time of the Goddess culture in Israel likely served a similar ritual purpose and held significant importance. Evidence from older wells found in Cyprus, near Paphos, dating back 10,500 years ago, supports this hypothesis [9]. In one of these wells, archaeologists discovered a woman’s skeleton along with jewelry, flint tools, and animal bones, indicating its ritual significance. It is probable that these wells symbolized the female genital organ, representing the womb of Mother Earth, similar to vaginal caves, but with the added motif of water [10].

Wells have long been linked with sexual symbolism and fertility, as well as with the notion of connecting to other realms and the potential for achieving eternal life. Consequently, legends have emerged about a mythical fountain of youth tucked away in a remote and secretive location. It’s believed that those who drink from its waters will gain immortality. This mystical well is also said to possess the power of enlightenment and wisdom, with its water capable of performing miracles. However, accessing it is no easy feat; it’s shrouded in secrecy, and seekers must undergo a rigorous initiation process to discover its whereabouts.

Put simply, to tap into the depths of our subconscious, symbolized by water and wells and often associated with femininity, one must undergo a process guided by feminine initiation and wisdom. This journey, which unfolds through dreams and visions, takes us into the realm of imagination, guided by the Goddess Mother who holds the secrets of water and life. Within these waters lie the potential for human growth and a profound connection not only to our inner selves but also to the vast universe and the celestial bodies above.

[1] In a later period, at the end of the Goddess culture, the bones were buried in secondary burial in house models, such as found in the cave in Peki’in. This shows the mythical and spiritual importance of houses.

[2] In these cultural settlements known around the world such as Çatalhöyük in Turkey or Vinča on the Serbian Danube, advanced houses with sophisticated and smart technologies of insulation, heating, light and space division are discovered.

[3] and if a wall appeared in them (as in Jericho, for example), then its function was not defensive but magical-symbolic, to symbolize the border between chaos and order – cosmos, which characterizes the place where Humans live.

[4] According to Rapunzel, man looked at the stars and recognized (and later modelled) the appearance of what he called “star visions” on Earth

[5] Therefore it was dangerous to stay in them, around them another digit of time-space was created, and the force was present. For this reason the stay in them was limited in time and for certain people (willing), around that aura of holiness on the other hand it was blessed to live.

[6] The miraculous birth and reproduction of the fish is one of the proofs of this

[7] This is the oldest symbol in the Egyptian hieroglyph script and it symbolizes flowing water.

[8] And so we find pebbles (related to water) on which grids in the shapes of squares and triangles are engraved.

[9] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8118318.stm

[10] Wells captured the rays of the full moon in folk mythology and thus fertilized the land.