This is a rudimentary translation of articles from my book “Goddess Culture in Israel“. While it is far from ideal, it serves a purpose given the significance of the topic and the distinctiveness of the information contained. I have chosen to publish it in its current state, with the hope that a more refined translation will be available in the future.

Sites of Goddess culture

One of the most significant transformations in human history was the agricultural revolution. People transitioned from living in caves, foraging for grains, and hunting animals to residing in houses and villages, cultivating and harvesting crops, and domesticating animals. The inception of agriculture, a miraculous development, was made possible with the guidance and support of the Goddess – Mother Earth. Fortunately, this agricultural revolution commenced in the Land of Israel and the broader Middle East region.

The culture of the Goddess spanned approximately 6,000 years, from the onset of the agricultural revolution around 9,500 BC to the advent of the urban revolution in 3,500 BC. Archaeologists term this era prehistory or the Neolithic period. For our purposes, we will refer to it as the Time of the Goddess Culture, dividing it into three distinct periods: the Beginning of the Goddess Culture Era (9,500-6,400 BC), the Middle of the Goddess Culture Era (6,400-4,500 BC), and the End of the Goddess Culture Era (4,500-3,500 BC). Quite straightforward, isn’t it?

From an archaeological perspective, the Beginning of the Goddess Culture Era aligns with the pre-Ceramic periods I, II, and III. The Middle of the Goddess Culture Era corresponds to the Ceramic Period, while the End of the Goddess Culture Era corresponds to the Chalcolithic Period. Throughout the book, you may encounter dual definitions of these periods in parentheses. While it may seem a bit intricate, this approach aids in conveying the message that a matriarchal Goddess culture flourished in Israel for thousands of years.

It’s crucial to grasp that during the era of hunter-gatherers, the Land of Israel sustained only a few hundred, perhaps a few thousand individuals. According to archaeologists, each couple typically had 2-3 children, and human communities consisted of 20-25 people. With the advent of agriculture, the population in Israel grew to around 20,000 individuals. While agriculture allowed villages to support larger populations, it also rendered them dependent on it. The transition to village life brought about significant changes both in physical existence and in the spiritual realm of the people. Subsequently, every few hundred years, the population doubled.

Jericho – the oldest settlement in the World

In the desert areas of the Jordan valley, near the Dead Sea, there is an Oasis called Jericho, which is the world’s oldest known settlement—a walled city where hundreds of people lived as early as 11,500 years ago. Nearby, other ancient sites such as Gilgal and Netiv Hagdud have also been discovered, featuring settlements from the same period. This concentration of ancient settlements raises the question: why did the agricultural revolution give rise to such a proliferation of settlements in this specific location?

Various explanations—climatic, geological, and historical—can shed light on the concentration of ancient settlements in Jericho. However, there’s also a spiritual and energetic perspective to consider: Jericho, situated 300 meters below sea level, holds the distinction of being the lowest city in the world, nestled within the Syrian-African rift. This rift, stretching over 6,000 kilometers from Turkey to Mozambique, has the same length as the Earth’s radius at the poles and is the longest and most noticeable valley in the world. According to the Gaia theory, which posits that the Earth is a living entity, different regions serve distinct functions. The Syrian-African rift could be seen as a sort of womb of the Earth, fostering the emergence of life. It’s no coincidence that the first hominids and Homo sapiens appeared along this rift. Furthermore, Mother Earth, nurturing humanity, birthed new forms of thought and life along this valley, including agriculture, which subsequently spread across the globe.

It’s fascinating to note that the transition to settled life and the advent of agriculture occurred in two significant locations: Jericho and the Göbeklitepe site in southeastern Turkey. Remarkable monumental structures have been unearthed at both sites: in Jericho, these include the tower and the wall, while Göbeklitepe boasts twenty round buildings constructed with fieldstones and supported by T-shaped megaliths adorned with glyphs. According to archaeologist Klaus Schmidt, who led excavations at Göbeklitepe, these structures served as temples commemorating the onset of wheat cultivation in the region, expressing gratitude to Mother Earth for this gift to humanity. Given the parallels between Göbeklitepe and Jericho, it’s plausible to consider whether the tower and wall of Jericho were also constructed for similar reasons—perhaps as symbolic expressions of gratitude to Mother Earth for the bounty of agriculture.

Archaeologist Ran Barkai, who examined the tower in Jericho [2], proposed that it served as a temple or ritual structure, akin to those found in Göbeklitepe. These structures were likely erected to signify the shift to permanent settlement and the advent of agriculture, as expressions of gratitude to the sun and the earth for their role in sustaining life. Schmidt, the excavator of Göbeklitepe, who visited the Jericho site, noted the presence of two additional buildings and two pedestals for large flags nearby, leading him to also speculate that the tower held religious significance, possibly serving as a temple.

In any case, the tower stands adjacent to an impressive wall stretching from northeast to southwest, positioned within the inner part of the wall rather than the outer, typical placement for fortification towers. Hence, it seems improbable that its purpose was defensive, especially considering that the wall did not encircle the entire settlement. Barkai posits that during this era, warfare was rare, life expectancy increased following the transition from hunting to agriculture, and there are no signs of widespread destruction or fire in the site. These factors suggest that such concerns of warfare were not part of the ancients’ worldview. Therefore, Barkai proposes that the tower and wall were not constructed for defensive purposes or to divert floodwaters, as suggested by other archaeologists, but rather for magical rituals and worship.

It’s somewhat perplexing to comprehend, but the individuals who constructed the tower had likely never encountered such a structure before. This prompts the question: where did they derive the concept of a tower? Let’s delve into some specifics: the Jericho tower stands at a height of 9 meters, with a diameter ranging from 7 to 9 meters. Notably, the tower’s base diameter matches its height, and it possesses a trapezoidal shape. Inside, the tower features walls measuring 1.5 meters thick, along with a corridor and a staircase comprising 22 steps leading to the roof.

The individuals responsible for constructing the tower likely descended from the Natufian civilization, predecessors who inhabited the region. While adept at building small round houses, erecting a tower of such magnitude required a considerable workforce. Barkai estimates that constructing the tower alone would have demanded 11,000 days of labor. When factoring in tasks such as plastering, excavation, quarrying, and transportation, it becomes evident that hundreds of people, supported by their families, toiled for many months to build both the tower and the wall. This suggests that Jericho and its surrounding area possessed sufficient manpower and food resources, indicating a reliance on agriculture rather than hunting for sustenance. Consequently, the transition to agriculture likely occurred concurrently with or prior to the construction, rather than afterward as some archaeologists suggest.

While no evidence of wheat cultivation has been unearthed in Jericho during the time of the tower’s construction (although future discoveries may shed light on this), it’s probable that other plants were cultivated. One of the earliest domesticated plants globally is the broad bean, whose wild variant is native to Israel. Seeds of this plant were discovered in the Nahal cave in Carmel, dating back to the Natufian culture approximately 14,000 years ago. Jericho boasts abundant springs, a warm climate, and the potential for irrigation, suggesting that wild beans or other cultivated plants may have been grown in the area at the time. It’s conceivable that, as a gesture of gratitude to Mother Earth for her bounty, the local inhabitants opted to construct a temple dedicated to the Goddess.

According to Barkai, the explanation for the tower’s shape and purpose can be found in the prominent nearby mountain, Quruntul Mountain to the west (also known as the Mount of Temptation), which dominates Jericho’s skyline. The tower is designed to mirror this mountain, and its interior features very steep spiral stairs that serve as ritual steps oriented towards the mountain. These stairs are not typical; rather, they require climbers to ascend on all fours, resembling a ladder or heavenly ascent. Beginning at ground level near the entrance, the stairs extend to the rooftop. Their orientation aligns with a 290-degree axis, linking the tower’s location to the summit of Mount Quruntul. Thus, ascending the tower’s stairs leads one to face the summit of Mount Quruntul upon reaching the rooftop.

Furthermore, when positioned 30 meters east of the tower along the axis of the stairs (290 degrees), one observes that the tower’s shape mirrors that of the mountain, appearing to merge seamlessly with it. The lower opening of the tower aligns with the base of the mountain. This architectural resemblance between the tower and Quruntul Mountain suggests a deliberate effort to reflect the natural landscape. Barkai proposes that the adjacent wall to the tower may represent the line of cliffs in the Judean desert below the mountain. This practice of mirroring the surrounding landscape was a characteristic of the Goddess culture, which viewed the environment as a living entity. Similar motifs are evident in settlements and other sacred sites, such as the renowned example of Lepenski Vir in Serbia, where houses were constructed to mirror a trapezoidal mountain situated across the Danube River.

But there’s more to consider: the orientation of the stairs and the axis of the tower toward the summit of Mount Quruntul align precisely with the direction of the sunset on the longest day of the year. During this time, the sun sets directly behind the summit of Quruntul Mountain, casting its pointed shadow directly into the circle of the tower. This phenomenon symbolizes a celestial union, where the sky seemingly penetrates and fertilizes the earth, creating a connection between the celestial and terrestrial realms. This divine union represents the convergence of heaven and earth, spirit and matter, and the merging of male and female energies. The circular shape of the tower further reinforces this symbolism. It’s challenging to dismiss these alignments as mere coincidence.

The longest day of the year held significant importance for the people of the Goddess culture. It symbolized the transition from a nomadic society, which revered the stars and the moon, to an agricultural society that placed great emphasis on the cycles of the sun. As the sun reached its zenith in the sky and light reached its pinnacle, plants reached their peak activity, serving as conduits between the universe and the earth. The extended daylight hours facilitated a connection between heaven and earth, made possible through the aid of plants and the nurturing energy of the Great Mother. This connection was epitomized by the Sacred marriage ceremony observed on this day, echoing the cosmic drama of the mountain’s shadow penetrating the tower.

In the excavations conducted in Jericho, approximately 70 large round huts constructed from mud bricks were unearthed, dating back to the early stages of the Goddess culture (pre-ceramic period A). It is speculated that each of these houses accommodated a single nuclear family. Alongside the residential structures, public buildings, likely serving as temples, were also discovered. Moreover, significant portions of the mound remain unexcavated to this day. Additionally, fragments of skeletons were uncovered, with some instances revealing skulls separated from the rest of the skeleton and interred in groups beneath the floor.

The various discoveries shed light on the religious practices of ancient civilizations: deceased individuals were interred beneath floors in a contracted position and covered with lime. Eliade suggests that this ritual was performed to honor the deceased and maintain a connection with ancestral spirits [4]. The Natufians were among the first to adopt this burial practice. However, with the advent of agriculture and the shift to settled village life, additional mythical and religious beliefs emerged. It appears that the veneration of the dead became intertwined with fertility rites and agricultural cycles, emphasizing the symbolic connection between seeds and burial. In this belief system, the deceased are seen as sharing the underworld with seeds, imparting their blessings upon them. Just as seeds sprout and grow, so too is the hope for resurrection of the deceased.

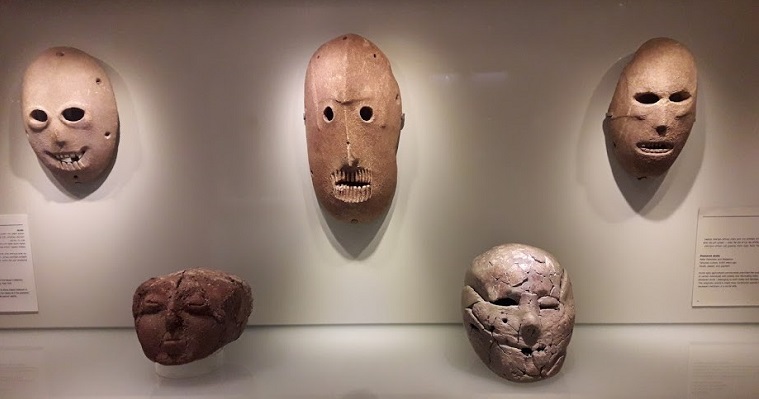

While it is accurate to say that the Natufians were among the first to separate skulls from skeletons in certain burials, the practice became particularly refined in Jericho. Following the consumption of flesh, graves were reopened to extract the skulls. A tradition of washing skulls, eventually progressing to wrapping them in clay, emerged, later evolving to include the addition of masks. Notably, during Kathleen Kenyon’s excavations in Jericho, a remarkable discovery was made: a collection of seven adorned skulls buried beneath house floors. These skulls were adorned with intricately decorated mud clay masks, with shells representing the eyes.

As previously discussed, the skull held significant symbolic value as the vessel for dreams, visions, and the spirit among these ancient peoples. Evidently, they imbued bones with magical properties, a belief that persists in certain practices within Christianity, such as the veneration of saints’ relics. The skull was viewed as a metaphorical seed capable of sprouting a new spiritual body after death. It is reasonable to infer that rituals were conducted involving these adorned and buried skulls, possibly within a designated space of significance, such as a temple, particularly considering the discovery of seven covered skulls together in one room during Kathleen Kenyon’s excavations.

In addition to the skulls, excavations in Jericho unearthed various artifacts including figurines depicting women and animals. Notably, archaeologist Garstang identified a trio of figurines representing a man, a woman, and a child as the ancient divine triad. Garstang suggested that the Jericho culture had interactions with settlements in Turkey such as Çatalhöyük and Haçiler. Indeed, evidence supporting the connection between Jericho and distant regions has emerged from excavations. Obsidian stones, imported from Turkey, were discovered in Jericho, indicating the existence of trade routes possibly facilitated by seafaring vessels. Additionally, basalt craters and axes found in Jericho were traced back to Gesher, located 100 kilometers away in the Jordan Valley. Gesher was known for its basalt tool workshop, suggesting an extensive trade network within the region. Furthermore, decorative green stones sourced from distant locations were also uncovered. These archaeological findings underscore the existence of a network of trade and mutual relations that extended across vast territories within Israel and beyond.

The Jericho settlement encompassed a relatively large area, with some estimates suggesting that over 2,000 individuals inhabited it a millennium after its founding, leading some to assert that it was the world’s first city. In close proximity to Jericho, other sites dating back to the early stages of the Goddess culture were discovered, including Nativ Hagdud (located 20 kilometers north of Jericho) and Gilgal. These findings suggest that the entire region was densely populated with intensive agricultural settlements. Similar sites from the same period have been unearthed throughout the country, such as Hatula in the Ayalon Valley, Gesher, and Nahal Oren.

Figs discovered in Gilgal hint at the possibility of cultivated fig trees, potentially pushing back the timeline for the domestication of fruit trees earlier than previously assumed. Additionally, archaeologists unearthed barley and oat kernels indicative of intentional cultivation. Among the findings was a square hut containing a concentration of small clay figurines depicting women and animals, including a bird. Some experts have proposed that this structure may have served as “the shaman’s hut.”

The clay figurines from Gilgal feature schematic representations of female figures, characterized by large eyes and breasts. Among the most notable is a seated female figure, standing at 42 cm tall, housed in the Israel Museum. This figurine displays open legs and a distinct double buttock, with some interpretations suggesting a combination of both female and male genitalia, represented by the joined head and body. Gimbutas asserted that the art of the Goddess culture excelled in accentuating the female genital organ and incorporating combinations of human, animal, and inanimate elements, a theory supported by the figurines found in Gilgal.

Another significant discovery at Gilgal was an abstract limestone figurine, depicting a figure combining a man with an egg, symbolizing the procreative attribute of the Goddess. Additionally, pebbles adorned with geometric patterns resembling meandering grids and waves were uncovered in Jericho, Gilgal, and Netiv Hagdud. These symbols align with Gimbutas’s interpretation of them as part of the symbolic language of the Goddess culture.

Tel Jericho, located within the territory of the Palestinian Authority, is easily accessible for visitors. The prominent tower and other remnants of the ancient city offer an impressive sight. Additionally, visitors can take a cable car from the site up to the nearby Quruntul Mountain, which held sacred significance for the ancient inhabitants of Jericho and is now revered by Christians as the Mount of Temptation. Perched on the cliffs of the mountain is a magnificent monastery, but delving into its story would be another adventure altogether.

Yiftahel settlement

The Beit Netufa Valley stands out as one of Israel’s most fertile agricultural regions. Situated at its southwest exit lies the ancient prehistoric settlement of Yiftahel, dating back to the pre-ceramic Neolithic period B, also known as “the beginning of the Goddess Culture era.” This settlement emerged approximately 1,000 years after the establishment of ancient Jericho, marking a period when agriculture began to play a more significant role in sustenance. Rather than a sudden revolution, this transition appears to have been a gradual process, with communities increasingly relying on agriculture as their primary food source. During this era, notable advancements were made in the domestication of crops, paralleled by developments in tools, particularly the hoe and pitchfork (as plows had not yet been introduced). These innovations played a crucial role in shaping the agricultural landscape of the time.

Agriculture became more intensive and expanded to encompass heavy soils in the valleys. Humans relied on it, adapted to it, and introduced complementary crops like lentils, chickpeas, and beans, which are rich in essential proteins. Villages expanded, mud brick usage became prevalent, and houses transitioned from round to square shapes. Alongside agriculture, a rudimentary lime industry emerged, along with the refinement of flint tools and the production of greenstone beads using flint drills. People mastered plaster use and the construction of mud bricks, resembling the stone technology depicted in “The Flintstones” animated series.

Yiftahel was a sizable settlement where archaeologists uncovered significant public structures. Among them, a workshop for lime and brick production, measuring 100 square meters, was unearthed. Another substantial building, likely a temple, was meticulously constructed but inexplicably concealed under a mound of dirt and identically sized stones, according to the excavating archaeologists.

Lentils and chickpeas cultivated by the locals were discovered at the site, marking the earliest known appearance of these crops in the world. This suggests that as far back as 11,000 years ago in the Galilee region, people were consuming hummus with pita bread, with each village possibly boasting its own unique variation of the dish. Concurrently, the domestication of goats and sheep occurred, leading people to transition from hunting to herding these animals.

The dwellings unearthed in Yiftahel stand out for their rectangular shape, boasting sizes twice that of the round huts discovered in Jericho and other ancient sites. While the round huts, constructed from stones and twigs, typically measured around 20-30 square meters, resembling a large room, the new houses in Yiftahel exceeded 50 square meters in area. These houses featured walls crafted from mud bricks and were occasionally partitioned into multiple rooms. Notably, they were constructed using advanced techniques, with lime-coated floors made from burnt chalk. Adjacent to the huts, beneath the floors, archaeologists discovered burials of individuals in a contracted position. One particularly poignant grave contained the remains of a contented family unit: a father, mother, and child, nestled closely together. The woman’s right arm lay beneath the man’s head, her left arm embraced the child, while the man’s left arm rested gently on the child.

According to Ofer Bar Yosef, the discovery of lime and plaster production workshops in Yiftahel marks the advent of pyrotechnology, a technology involving high-temperature production processes, which laid the foundation for advancements in pottery and metallurgy. Disparities in the quantity of lime and plaster among the houses, as noted by Bar Yosef, suggest the onset of social stratification. He posits that lime preparation was labor-intensive, involving the gathering of chalk stones and wood, kiln construction, prolonged operation, mixture preparation, and casting—a process affordable only to the wealthy. Alternatively, I propose another interpretation: during that era, production workshops, such as weaving and baking, might have been communal rather than private, similar to lime production. The allocation of lime among the houses could have been based on the function of each structure. Furthermore, considering lime’s role in burial practices, differences in floor composition across buildings could be attributed to the importance of buried individuals beneath them.

Nonetheless, in a pit adjacent to one of the buildings, archaeologists uncovered three skulls, each covered with a plaster mask—a pioneering find marking the earliest known appearance of masks in a burial context. Masks held significance as soul anchors, utilized in shamanic rituals during life and believed to aid the soul in the afterlife. The burial masks featured shell eyes, reminiscent of those found in Jericho, and limestone noses. The notion behind their placement was to magically awaken the deceased’s perception and sensation in the realm beyond through the incorporation of the mask and its intricate features.

In one of the graves, a horn of a wild bull was discovered, possibly echoing ancient beliefs in the lord of the animals and symbolizing the rejuvenation of the earth. These horns resemble those found in other major agricultural settlements of the era, such as Çatalhöyük in Turkey, where they were viewed as symbols of divine presence and earthly energies. During this period, neither cows nor bulls were domesticated, likely holding significance as totem animals in shamanic rituals. It’s worth noting that bull horns have been attributed with magical properties in various alternative theories and global folklore, believed to aid in soil fertility and plant growth.

The discoveries in Yiftahel indicate that a millennium following the emergence of Goddess culture and the advent of agriculture, human civilization witnessed significant advancements. Across the globe, large settlements arose, primarily sustained by agricultural practices. Humans mastered the construction of mud brick structures and transitioned from inhabiting rocky terrain to fertile plains. Notably, Turkey hosts a mega settlement named Çatalhöyük, boasting around ten thousand inhabitants and featuring sophisticated dwellings constructed with mud and plaster walls, among other innovations.

After a millennium of experimentation since the inception of plant cultivation and permanent settlement, it appears that the Goddess deemed the time right to advance the human experiment. Those who had demonstrated their worthiness were allowed to progress into full village life, relying entirely on agriculture for sustenance. To facilitate the next stage of development, she bestowed upon humans new crops to diversify their diet and domesticated animals to eliminate the need for hunting. The Goddess instructed them in organizing life within a large community, fostering the development of crafts such as weaving, toolmaking, and plastering. She adorned them, teaching sacred dance and music, and imparted the knowledge of ceremonies and holidays to ensure the fertility of the land.

The Motza settlement

A few years back, a remarkable discovery was made near Motza, not far from Jerusalem, unearthing a vast settlement dating back 9,000 years ago, around 1,000 years after Yiftahel. Among the findings from the excavations were figurines depicting human faces, as well as one portraying a bull, indicating beliefs in the spirit world (where faces symbolized spirits) and the earth’s energies (with the bull representing them). Additionally, figurines combining female forms with those of eggs or birds, reminiscent of discoveries at Shaar Hagolan, were unearthed. Noteworthy artifacts include obsidian, a volcanic glass likely imported from Anatolia or Armenia, suggesting trade connections with distant lands. Seashells from the Red Sea were also found, underscoring the significance of water and indicating trade with regions afar. Moreover, the discovery of jewelry and abstract symbols etched onto bones reveals a numerical language, showcasing the religious significance of bones and a sophisticated level of intellectual thought.

In the settlement, archaeologists uncovered numerous significant structures, including large public buildings and places of worship, alongside hundreds of spacious residences, most of which were of the round variety, featuring plastered floors. The meticulously planned streets and warehouses stored agricultural staples like lentils and chickpeas, indicating a robust agrarian economy. Evidence of extensive animal husbandry was also discovered.

Among the artifacts found were bracelets, jewelry, and alabaster pendants, as well as a cache of flint blades exhibiting advanced chiseling techniques. It’s hypothesized that a flint blade production facility operated within the settlement, possibly utilizing heat to aid in chiseling. Similar stone tool production centers have been unearthed elsewhere in Israel, such as at Gesher in the Jordan Valley, where hard basalt stone was fashioned into blades, grinding bowls, and axes, then distributed across the region.

The establishment of such a sizable settlement in the Judean Mountains raises questions about its purpose. Given the limited agricultural land and the fact that the factories alone couldn’t sustain the population, other factors may have been at play. One possibility is a religious significance attributed to the area, suggesting that even in ancient times, the vicinity of Jerusalem held sacred significance. While this remains a hypothesis without empirical evidence at the time of writing, it offers a potential explanation for the settlement’s location.

Nahal Hemar Cave

In a cave located in Nahal Hemar within the Judean desert, researchers uncovered significant, distinctive, and unexpected artifacts dating back to the early stages of the Goddess culture. Among these discoveries were threads, linen fabrics, mats crafted from plant fibers, wooden beads, baskets coated with asphalt, and an assortment of bone tools, notably a sickle fashioned from a goat horn with flint blades, originating from 10,000 years ago. Typically, artifacts from this era consist solely of stone tools due to the decomposition of organic materials. However, in the arid environment of the Nahal Hemar cave, these organic items were remarkably preserved, providing invaluable insights into the vibrant daily life of ancient villages. These findings underscore the pivotal role of weaving and other crafts, predominantly carried out by women. Such evidence strongly suggests that inhabitants of ancient settlements were clothed and lived in dwellings offering considerable comfort.

An integral aspect of the agricultural revolution was the introduction of flax cultivation, providing the raw material for clothing and fabric production. Alongside this innovation, the domestication of sheep and goats facilitated the spinning of wool, likely leading to the early development of the loom during the transition to agriculture. The discoveries in Nahal Hemar offer valuable insights into the ancient practices of weaving and spinning, shedding light on the early stages of these industries.

Among the discoveries in the cave were ritual objects, offering a window into the spiritual beliefs of ancient societies. Alongside animal figurines, the cave yielded painted covered skulls, masks, and bone carvings of human figurines adorned with various colors. These findings collectively highlight the significance of color within the context of the Goddess culture, providing compelling evidence of its cultural and religious importance.

Near Petra

In the 1950s, archaeologists unearthed an ancient settlement known as Beidha, located near Petra. Dating back approximately 13,000 years, Beidha’s earliest traces of human habitation originate from the Natufian period. However, its significance lies in the remnants dating back 9,300 years to the time of the Goddess. Beidha boasts some of the world’s oldest known houses and temples, indicating its importance as a center of early civilization. Historical records suggest that over 200 individuals resided in Beidha, engaging in agricultural and pastoral activities.

Initially, the inhabitants of Beidha dwelled in round houses. However, approximately 9000 years ago, they began constructing large rectangular houses. The Jordanian Antiquities Authority has undertaken restoration efforts on some of these ancient dwellings, providing visitors with a glimpse into the lifestyle of the period and the transition from round to rectangular housing, a trend observed elsewhere in the region, including Israel. What makes visiting the site of Beidha particularly captivating extends beyond its picturesque landscape. Visitors have the unique opportunity to step inside these meticulously restored houses, offering an authentic portrayal of life at the dawn of civilization. In this regard, Beidha stands unparalleled in both Israel and Jordan.

The site was unearthed and explored by British archaeologist Diana Kirkbride, a colleague of Dorothy Garrod, renowned for her significant excavations across the West Bank and Jordan prior to 1967. Kirkbride’s research revealed that the residents of Beidha were agrarians, benefiting from a wetter climate during that period. They practiced animal husbandry, raising goats and sheep, while also engaging in hunting and gathering plant resources, resembling the lifestyle of modern-day Bedouins. What’s particularly intriguing is the discovery of imported raw materials, such as shells from the Red Sea and obsidian stone from Anatolia, suggesting extensive trade networks and connections reaching far beyond Beidha’s immediate vicinity.

The sculptures of Ain Ghazal

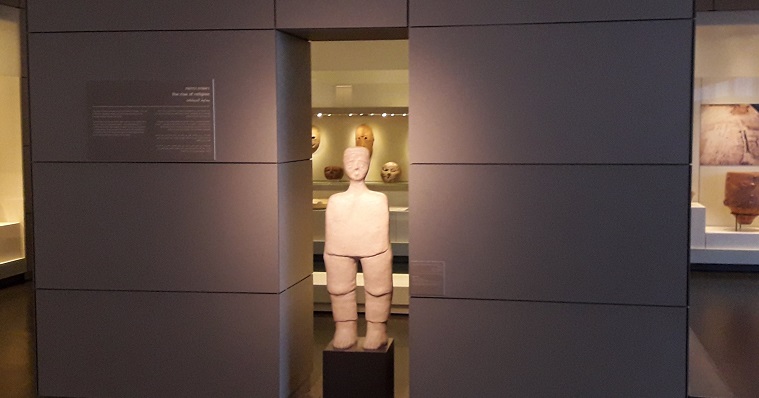

Visitors to the prehistoric exhibition halls of the Israel Museum are greeted with a striking sight: a sizable statue depicting a large white figure with thick, rounded legs, a square torso, and wide-open eyes. This remarkable sculpture marks the earliest known instance of monumental art, standing at over one meter in height and dating back over 9,000 years. Discovered amidst the ruins of the ancient settlement of Ain Ghazal in present-day Jordan.

Ein Ghazal was a substantial settlement, accommodating over 3,000 individuals who sustained themselves primarily through pastoralism and agriculture. They tended flocks of sheep and goats while cultivating crops such as wheat, chickpeas, beans, and lentils. Remarkably, Ein Ghazal stands as one of the earliest examples worldwide of a settlement of this magnitude predominantly reliant on agriculture. In contrast, preceding settlements like Jericho did not reveal evidence of agriculture and sheep-rearing on such a grand scale. Jericho itself was smaller in size, as were neighboring settlements, with the exception of a recently discovered settlement near Motza, which shares a similar population size to Ein Ghazal.

Essentially, what we witness here is a shift from relatively modest agricultural settlements, similar to those found elsewhere globally, to expansive settlements and intensive agriculture in fertile regions. While humans had yet to develop ceramics, they mastered the technique of mixing mud with straw, sun-drying it, and crafting bricks. Furthermore, advancements were made in the production of lime and plaster, materials utilized for constructing houses and crafting sculptures of unparalleled craftsmanship, unmatched elsewhere in the world. It appears that the Earth bestowed generously upon humanity, fostering a connection that allowed them to harness its resources and unlock its treasures.

Prior to the era of Ain Ghazal, villages in the western region of the Jordan Valley were constructed either entirely or partially using stone slabs, a building method also observed in other parts of the world. For instance, the ancient tower in Jericho was constructed from stone. However, as settlements expanded into more fertile and spacious areas, there was a notable transition to the widespread use of mud bricks. The earliest instances of such bricks were unearthed in Jericho around 10,000 years ago, marking a significant technological advancement that opened up numerous new possibilities in construction and settlement development..

The name “Ain Ghazal” translates to “the spring of the deer,” a fitting appellation for the ancient settlement given the inhabitants’ engagement in hunting activities, particularly deer hunting. Situated along the banks of Nahal Yabok, Ain Ghazal occupies fertile land conducive to intensive agriculture. In antiquity, the surrounding area boasted forests utilized by the local population for various purposes. Additionally, plants found along the stream’s banks were woven into baskets by the inhabitants, showcasing their resourcefulness and adaptation to their environment.

The most significant discovery at Ain Ghazal was a collection of large, human-like statues, each standing at approximately one meter in height. This discovery marks the earliest instance of large-scale sculpture in human history, often considered the dawn of the art of sculpture itself. Ancient artisans at Ain Ghazal employed a meticulous process to craft these statues. They constructed the skeleton of the statues using a combination of plaster and reeds, which they then wrapped with fibers and additional layers of plaster. Finally, the figures were formed using layers of white plaster. Once the basic form was established, the statues were adorned and painted. Eyes were accentuated with black tar sourced from the Dead Sea, while hair, beards, and facial features were carved and painted onto the plaster. The final result was a series of striking sculptures, resembling otherworldly figures or avatars, reminiscent of the archaic statues of Greece (Kouroi) and those found in ancient Egyptian art. It’s noteworthy that the Ain Ghazal sculptures predate both of these artistic traditions by thousands of years.

In Ain Ghazal, numerous statues were unearthed, with many discovered within what can be described as a “treasure pit.” These statues varied in form, ranging from standing figures to busts depicting the head and upper body. Among them, some statues displayed a unique feature: a square-shaped body with two heads. This peculiar design has been interpreted as representing the concept of male and female androgyny, symbolizing the principle of duality. If this interpretation holds true, it serves as evidence of the abstract and sophisticated thinking of the Ain Ghazal people. However, alternative theories have been proposed regarding the statues’ origins and meanings. Some speculate that they may depict representations of extraterrestrial beings, suggesting that certain statues with two heads could support such a hypothesis (albeit a speculative one).

The abundance of statues found in a single location suggests their connection to religious worship, particularly within a context where the appearance of the double head symbolizes the reproductive aspect associated with the Goddess. One notable statue depicts a woman holding both her breasts in her hands, prominently protruding them forward. This characteristic gesture is reminiscent of ancient Goddess figurines discovered at sites like Shaar Hagolan. Such representations likely served as sacred symbols embodying fertility and nurturing aspects associated with the divine feminine.

In his groundbreaking book “Inside the Neolithic Mind,” Lewis Williams delves into the significance of the statues found at Ain Ghazal. He suggests that the representation of eyes in these sculptures, particularly with enlarged pupils, is indicative of trance states. Furthermore, he suggests that the layout of the settlement itself reflects shamanic perceptions of the universe. The arrangement of distinct areas within the settlement allows for movement akin to that of a shaman navigating various spiritual realms. Drawing from these observations, Williams concludes that the religion practiced at Ain Ghazal was shamanism.

Genetic examinations of skeletons at Ain Ghazal have revealed intriguing connections to the Natufian culture and prehistoric settlements in Israel, particularly in the Jericho area. Archaeologists speculate that individuals from Jericho, which was abandoned during this period, migrated to Transjordan and established the settlement of Ain Ghazal, suggesting a cultural continuity between these neighboring regions, only a day or two’s journey apart. The reasons behind the migration from Jericho to the plains of Moab remain uncertain, although changes in climate following the conclusion of the ice age are considered a potential factor. Additionally, genetic testing has revealed the presence of individuals from Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) at Ain Ghazal, indicating connections with the larger settlements of the Goddess culture in Anatolia, such as Çatalhöyük.

Numerous graves have been unearthed at the site, showcasing two distinct burial practices: some individuals were interred beneath the floor, with their skulls later removed from the skeleton and encased in plaster, a custom observed in Jericho and other ancient settlements in Israel. Conversely, other individuals received no such special treatment, their complete skeletons discarded in refuse pits. Archaeologists interpret these burial patterns as evidence of class distinctions within the population, signaling the onset of social stratification. However, an alternative perspective suggests that the sanctity attributed to the head may have prompted its separation from the skeleton. This reverence for the head may also be reflected in sculptures featuring double heads. It’s plausible that only those individuals deemed spiritually advanced, possessing a “double head” or enlightenment, received ritual burials, while others were deemed “ordinary” and received no special treatment. Thus, while a two-class society indeed existed, its division may have been spiritual in nature: between the enlightened and the ordinary.

However, Currently there isn’t much left to see at the historical site of Ain Ghazal. Many of the sculptures uncovered there have been moved to the Jordan Archaeological Museum, with some housed in the Israel Museum and one in the Louvre.

Ain Ghazal and the settlement at Motza stand as the largest settlements in Israel dating back to the early stages of the Goddess culture, a period lasting approximately 2500 years out of 6000. It’s noteworthy that these two sites are situated opposite each other, flanking the Jordan Valley in the highlands. While in other regions people migrated from mountains to plains during this time, in Israel, they departed from the fertile Jordan Valley, possibly due to climatic shifts, and settled in elevated areas. Additionally, several other sites from this era merit mention, including Bismun and Tel Te’o in the Hula Valley, where early grain crop remains were discovered; Tel Ali near the Sea of Galilee; Kfar Hahoresh in the Galilee, notable for its covered skulls findings; Hatula in the Ayalon Valley; Batashi Mounds in the Judean Hills; Munhat and Gesher in the Jordan Valley; and finally, Atlit Yam.

Atlit Yam

The final site from the initial phase of the Goddess culture, which we’ll discuss, is presently submerged underwater. Located not far from Atlit, approximately ten meters beneath the surface, lies Atlit Yam, one of Israel’s oldest settlements, dating back over 8,000 years. During that era, the Mediterranean Sea’s water level was significantly lower than it is presently, and the site thrived as an ancient fishing village along the coast. However, with the subsequent rise in water levels due to the melting glaciers at the conclusion of the Ice Age, the settlement was deserted and eventually submerged beneath the waves.

Many of the earliest settlements worldwide were situated near water sources, whether freshwater or saline. Fishing provided a supplementary and enduring food source, as evidenced by sites like Ohalo near the Sea of Galilee or Lepenski Vir on the Danube’s banks. However, beyond the practical benefits, residing near a water source, or the sea, likely held ritual significance as well. For instance, at Atlit Yam, the world’s oldest stone circle was unearthed, consisting of seven large stones, some measuring up to 2 meters, arranged in an open semicircle facing northwest.

The number seven holds typological significance and is associated, among other things, with the remarkable and intriguing observation that we perceive through a spectrum of seven colors and hear through a range of seven sounds. Additionally, when observing the sky, seven colors are discernible in the rainbow, along with seven celestial bodies moving amidst the backdrop of the fixed stars (Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn). Consequently, the number seven holds sacred importance across various cultures, suggesting that the discovery of seven stones within the circle at Atlit Yam is likely not coincidental. Adjacent to the circle, which boasts a diameter of 2.5 meters, stone slabs adorned with numerous cups were uncovered. Elsewhere, a ritual site was unearthed, featuring three oval stones standing at the height of a man, each with lateral notches, forming a human figure within them.

In addition to the ritual stone circle, houses with floors arranged around a central courtyard, paved streets between the houses, the ritual facility, and the stone slabs, another remarkable discovery was an 8,000-year-old well, ranking among the oldest wells globally. This well attests to the advanced technical skills of the local inhabitants. Intriguing artifacts were found within the well, including a limestone object shaped like a male genital organ. This finding potentially indicates its ritualistic significance, akin to similar artifacts found in ancient wells in Cyprus dating back to the early stages of the Goddess culture.

Near the houses and within them, archaeologists discovered 15 graves containing skeletons, the majority of which were in a fetal position, with the head oriented westward and the face directed southward. Some of the artifacts and illuminating photographs from the site are on display at the Moshe Shtekalis Museum of History in Haifa. These findings bear striking resemblance to those unearthed at a comparable settlement established a few hundred years later at Shaar Hagolan, which evolved into the largest and most significant center of Goddess culture in the region.

Comments

[1] Jericho is also considered the key to the Land of Israel, and Israel is more or less in the center of the land mass of the world. More on this subject in the “Secrets of the Earth” chapter below.

[2] Barkai, R., & Liran, R. (2008). Midsummer sunset at Neolithic Jericho. Time and Mind, 1(3), 273-283

[3] The first cultivated varieties of broad beans in the world were found in the Galilee 10,000 years ago.

[4] The identification was accepted by Eliade in his book “History of Beliefs and Religions”, Volume I.

[5] You can read about these stones in Tamar Noy’s book, “The Figure of Man in Prehistoric Art in the Land of Israel”, Israel Museum Publishing, Jerusalem.

i am interested in the masks found in your country , can i get writing about their discovery , what is the price of such a photo , will it be possible to buy the copyright